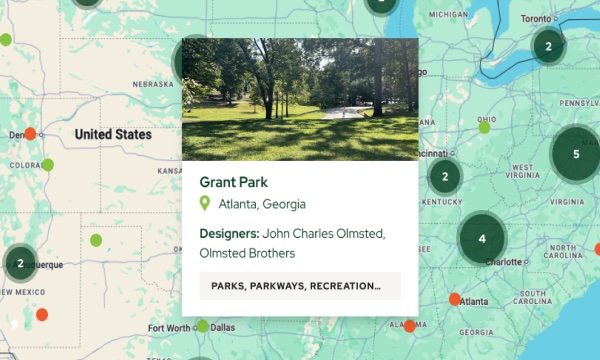

No aspect of the Olmsted firm’s work is more important — and more often overlooked — than its contribution to the history of city and regional planning in the United States. Landscape architecture, as Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux first defined the term, was itself a new form of American urbanism. As Lewis Mumford wrote in 1931, “By 1870, less than twenty years after the notion of a public landscape park had been introduced in this country, Olmsted had imaginatively grasped and defined all the related elements in a full park programme and a comprehensive city development.” By the 1880s, as the Boston park system was taking shape, the apprentice Charles Eliot was already responding to Olmsted’s suggestions of how park planning could extend to the regional scale. Regional planning in the United States subsequently developed from its roots in regional park plans (such as Eliot’s metropolitan Boston parks) just as city planning had origins in municipal park design.

City and regional planning demanded legal expertise, statistical analysis and other skills unfamiliar to traditional landscape designers. By the early twentieth century landscape architects were expected to collaborate with engineers, architects, lawyers and others to devise a range of regulatory and design solutions to the problems of urban growth. The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago was an influential example of multidisciplinary collaboration, as was the 1901 effort to replan Washington, D.C., for which Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. assumed his father’s role. Between 1907 and 1917, a new profession was born as more than one hundred American towns and cities established comprehensive city plans. A full partner in the firm since 1897, Olmsted Jr. was a leading practitioner and, as historian Susan L. Klaus notes, the “chief spokesman of the planning movement during its formative years.” In 1910, for example, he was working with the architect Cass Gilbert on a plan for the city of New Haven that utilized extensive data on demographics, tax rolls and industrial trends. The next year he published similar surveys of Pittsburgh and Rochester that also assembled unprecedented statistical information for those cities. In 1909 the Harvard School of Landscape Architecture (begun under Olmsted Jr. in 1900) offered the country’s first professional instruction in “City Planning,” and in 1917 Olmsted Jr. and the lawyer Flavel Shurtleff founded what became the American Institute of Planners.

By the 1920s city planning necessarily expanded to address entire metropolitan regions, a development presaged by the Olmsted firm’s work not only in Boston, but also for clients such as Essex County, New Jersey, beginning in 1898. The first county park system in the country, this regional park plan integrated municipal and county parks and parkways. Olmsted associates of the period, especially Warren Manning, continued and expanded the regional planning ideas of the Olmsted firm, and so the full significance of the firm’s city and regional practice is not to be found in this Master List alone. Many of the regional and even national park planning projects of the New Deal of the 1930s, for example, were the fruition of ideas that traced their origins back to the Olmsted firm office in Brookline, Massachusetts. It was especially appropriate, then, that Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s National Resources Planning Board, which oversaw federal park and resource planning, had as its executive the landscape architect Charles W. Eliot II, Charles Eliot’s nephew.