The Olmsted firm’s landscape work for public buildings spans about 100 years. The nineteenth century planning for public buildings by Frederick Law Olmsted was characterized by its curvilinear grace, stately proportions and fitting enhancement for the structure to be served. In the City Beautiful period, the firm designed grounds of public buildings with more axial formality, to serve as decorative anchors for the municipalities. Later, in the 1920s and 1930s, civic enrichments were often memorial projects (such as the Newton City Hall and War Memorial in Newton, Massachusetts, or the Robbins Memorial Town Hall in Arlington, Massachusetts). Regardless of style, the Olmsted firm maintained a notable design aesthetic, which gave dignity of setting to projects large and small. The work for public buildings from the Olmsted Associates era (1962-1979) was less extensive, consisting of consultations on earlier projects with some new library work (such as the West End Branch Library in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Rice Library in Kittery, Maine).

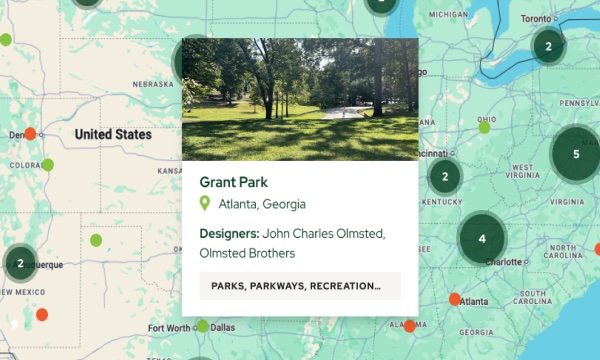

The practice of the Olmsted firm included about 150 listings for the grounds of public buildings of all types, of which approximately 100 generated at least one plan. The largest group in this category is the group of libraries (about 34 listings), followed by projects for municipal buildings such as city and town halls (15 listings), civic centers (11 listings), court houses (3 listings) and utilitarian structures such as incinerators (3 listings). Museums and various art-related institutes account for another twelve listings, many of which were projects that generated a considerable amount of work over several decades, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Cleveland Art Museum.

However, the most prominent sub-type within this thematic category is the work done for capitol buildings (11 listings), the oldest and most notable being the iconic design for the United States Capitol begun by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1874, a project that actively continued to the first decade of the twentieth century. Also beginning in the 1870s, the firm planned the New York State Capitol, a design collaboration of Frederick Law Olmsted and architects H. H. Richardson and Leopold Eidlitz; as well as Bushnell Park abutting the Connecticut State House in Hartford. The successor firm of Olmsted Brothers continued to work on state capitols, its most prominent commissions being those for the grounds of the Washington Capitol at Olympia, the Kentucky Capitol at Frankfort and the Alabama Capitol at Montgomery. Smaller projects included more limited work for the Utah Capitol in Salt Lake City, the Maine Capitol in Augusta, the North Carolina Capitol at Raleigh and the Pennsylvania Capitol at Harrisburg, as well as other states where the firm was consulted about capitol work.

There are various miscellaneous but important public building projects included in this thematic category, such as planning for the White House in Washington, D.C., or for the Maine Governor’s Mansion in Augusta; and for military establishments such as the Armory in Ansonia, Connecticut, the Schuylkill Arsenal in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, or the Jeffersonville Depot in Jeffersonville, Indiana, where Frederick Law Olmsted again worked with Montgomery Meigs, who had directed some of the United States Capitol construction. The emergency wartime planning that engaged much of the time of Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. during 1917-1918, and in which many of the firm’s apprentices were involved, was for the United States War Department to plan military cantonments and bases for the armed forces rapidly deployed as the United States entered World War I. There are several caveats that should be understood in the consideration of entries in this and other thematic categories. For example, there are numerous cross-overs in the references for projects such as the White House. While this project seems to indicate only three plans, all from 1903, many other plans and documents were prepared in the 1930s as a component of the extensive multiple-project planning for the Fine Arts Commission in Washington, D.C., labeled for “the Executive Mansion,” and found in the category Miscellaneous Projects. Additionally, some of the public building work came about as an element in more extensive and varied planning within a community, sometimes sponsored by a particular patron, such as Mary Curtis Bok for the Rockport Library Park in Rockport, Maine, and Camden-Rockport Information Bureau in Camden, Maine. Therefore, the researcher must consider creative linkages when exploring these various categories and look for references for any project under other project listings in a location or under a sponsor.