“Goodwin’s Wilds” includes an area of old-growth floodplain and riparian forest located on the North Branch of the Park River in Hartford, CT. It is a landscape that was traversed frequently and documented in the 1800’s by Frederick Law Olmsted, Hartford’s native son and the founder of landscape architecture.

In a letter to Charles Pond (June, 1871), Olmsted recommended the land adjacent be considered as a site for Trinity College (Job No. 00601) and that the entire river corridor extending down to Pope Park be protected as public grounds with significant beauty and convenience and “at little cost to the growing city.” Olmsted saw protecting these wild places as integral to the health of the city. The old forest Olmsted referred to is part of the former estate of James Goodwin, thus the name “Goodwin’s Wilds.”

Nearly 150 years later, Olmsted’s assessment was affirmed by the Connecticut Environmental Review Team (ERT, 2000): “this significant riparian zone should be prioritized for conservation…”

Goodwin’s Wilds is a remarkably rare habitat type in Southern New England. Few intact floodplain forests remain because of our history of extensive land-clearing and agriculture, particularly in the highly coveted and productive farmland of the Connecticut River Valley. But here are American beech, American sycamore, eastern hophornbeam, northern red oak, red maple, shagbark hickory, sweet birch, and white oak. The oldest of these that was cored and verified was white oak (~272 years old), followed by shagbark hickory (217+) and American beech (136). Recently, Goodwin’s Wilds was added to an inventory of old-growth in Connecticut.

The forest has been visited by ecologists, climate scientists, biologists, historians and others. Without a special designation or protection, even though most of it is a regulated floodplain, it could be damaged accidentally.

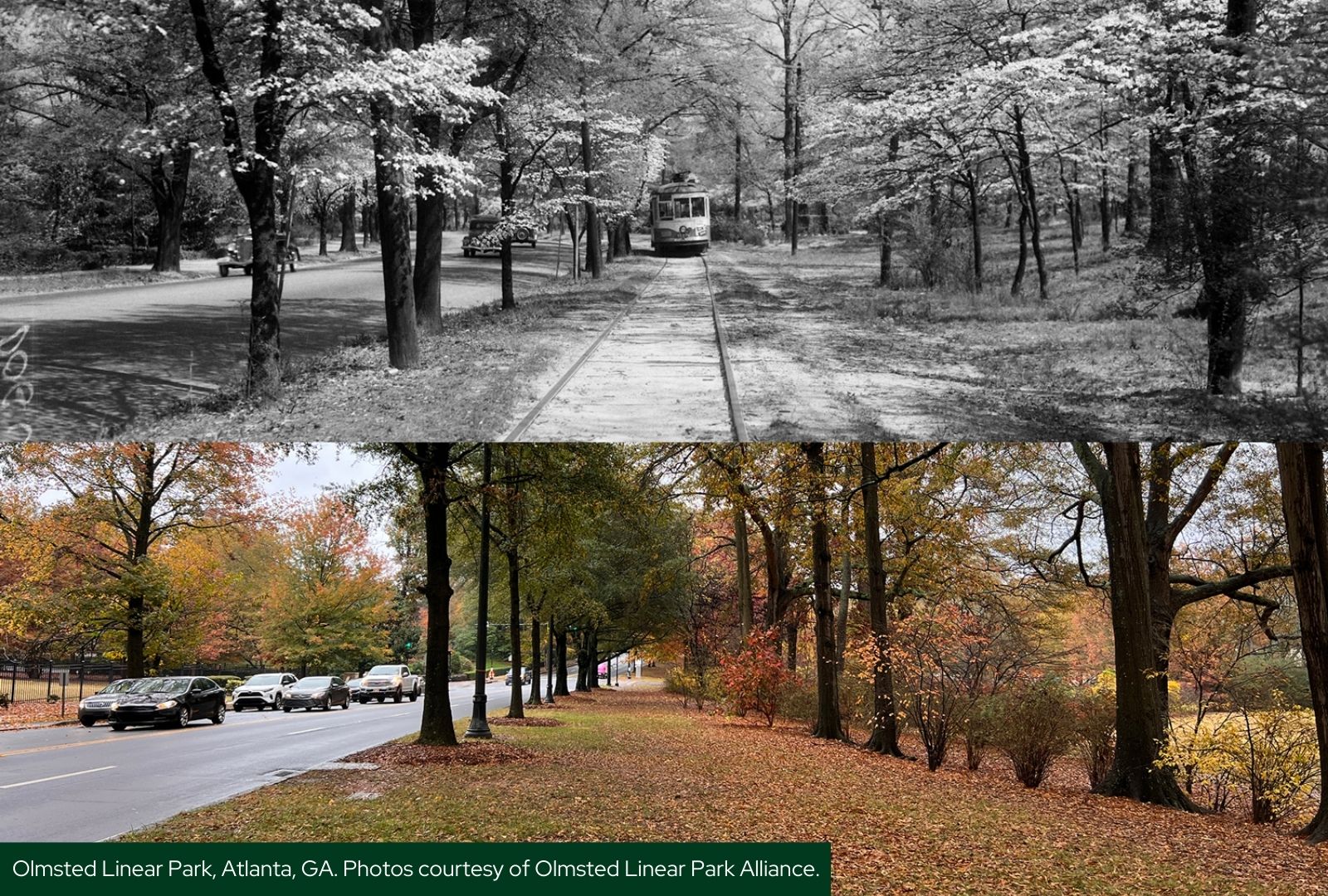

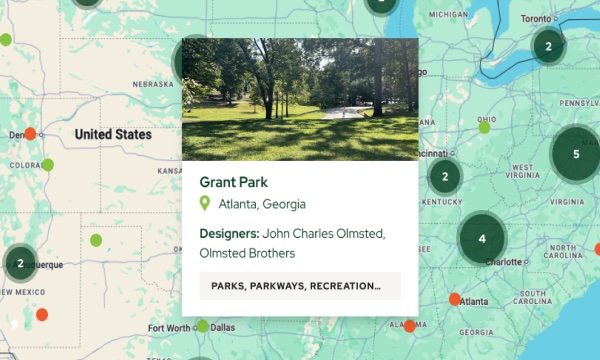

Protecting this forest in honor of the 200th anniversary of Olmsted’s birth (www.olmsted200.org) would be a landmark opportunity for Hartford to inaugurate a “Community Wilds,” similar to the “Urban Wilds,” “Urban Wilds” program established in Boston nearly 50 years ago to protect special pieces of nature for their history and their contributions to education, ecology, health, climate, and more. Another candidate is the Ten Mile Woods, Olmsted’s childhood landscape. It is nearly an old-growth forest and part of Olmsted-designed Keney Park (Job No. 00803).

A Community Wilds designation would highlight how and why this area is special and preserve the opportunity for ongoing scientific study. Recognition would 1) honor Olmsted’s vision and legacy; 2) ensure that special care is taken to not damage the forest; 3) preserve it as a refuge for all species and 4) protect it as a natural site for scientific study for future generations.

Protecting it would also advance the holistic urban planning that Olmsted brought to America’s cities – an approach that city planners must and should adopt today. Olmsted and the Olmsted firm emphasized thinking at the scale of problem, focusing not on individual pieces of land, but at green spaces, collectively, relying on regional planning to optimize environmental, economic, cultural, and civic interests.

To learn more, visit https://www.boston.gov/departments/parks-and-recreation/urban-wilds-program

Susan Masino, PhD, is the Vernon D. Roosa Professor of Applied Science at Trinity College and a member of the Olmsted 200 Higher Ed Working Group.