The years 1982 through 1994 saw multiple visual art exhibits every year in Prospect Park. The photographs, promotional flyers, correspondence and news clippings in the Archives shed light on the relationship between art in the park and broader cultural currents in the U.S. in the not-so-distant past.

In the 1980s Prospect Park was beginning to emerge from some tough decades of fiscal crisis and neglect. Back in 1976, a windstorm caused the 25-foot-high bronze figure of Columbia to fall out of her chariot at the top of the Grand Army Plaza Arch (formally, the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch).

In 1980, Mayor Edward Koch announced a ten-million dollar plan for the restoration of Prospect Park. Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis was able to procure federal funds that paid for a new position, administrator for Prospect Park. Appointee Tupper Thomas began to usher in a slow renaissance, fixing and reopening many vacant, vandalized buildings. Columbia was lifted by crane back into place, and after other repairs the public was invited to climb the spiral staircase and see the bird’s eye view of the park and the Manhattan skyline.

The federal funding also allowed Tupper to provide free public programs, which she felt was essential to entice people back into the park and change its reputation as crime-ridden and abandoned. A visual arts program was started and a staff curator, Mariella Bisson, exhibited art twice a year in the chamber at the top of the Arch. [To be clear, the NYC Parks Department has had a public arts program since 1967 that installs temporary artworks in public spaces in the five boroughs, including Prospect Park.]

Another grand space in Prospect Park, the Boathouse, had come within one day of being demolished in 1966 (a story for another day). During the 1970s, the restored building suffered repeated vandalism and break-ins. Mayor Koch provided city funds and the Boathouse was restored again and reopened in 1985 as a visitors’ center. Bisson used the high-ceilinged first floor as an art gallery.

The following year at the Boathouse Gallery, The Bridges of Prospect Park: Art and Architecture featured Harvey Dinnerstein, a local and well-known painter. He was quoted in the brochure as saying, “I have painted various tunnels in Prospect Park over the years, usually with a view toward the dark passage opening up into the light beyond, ever changing in various seasons of the year. The bridges or tunnels suggest to me a crossing, the human passage in space and time.”

Meanwhile, the landscape surrounding the Boathouse was used for the first time as an outdoor gallery, with large contemporary sculptures set dramatically against the water’s edge.

Exhibits at the Arch continued to be themed and site-specific, with titles such as Wings Over Brooklyn: Contemporary Sculpture on the Theme of Angels; Sculptors and the Spiral; Better Homes and Monuments; Hail Columbia: Sculpture in Praise of Women; and Eighteen Horses: Ninety Years of Equestrian Statuary. In 1991, the Arch closed for roof repairs. A new curator, Melissa Benson, was hired to organize the first exhibit in the Arch after its reopening, in 1994. That exhibit would affect the park’s relationship to visual art for years to come.

Trophies from the Civil/(Wars) was described by curator Benson as twelve artists examining civil wars and their rewards (trophies), whatever that meant to the artists. What it meant to one of them, Dread Scott, was expressed in a mixed media installation called El Grito.

To give some context for the controversy that would follow El Grito: in the 1980s and 1990s, perceived immorality in artwork led conservative groups and lawmakers to attack government funding for artists. Works by Andres Serrano (Piss Christ) and Robert Mapplethorpe (The Perfect Moment) were condemned by conservative groups such as the American Family Foundation, which sent protest letters to every member of Congress. In response, Senator Jesse Helms was able to pass an amendment restricting the use of public funds for what he judged obscene.

The artist Dread Scott was born Scott Tyler; his adopted name refers to Dred Scott, the plaintiff in what is considered the worst decision made in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court, Dred Scott v. Sanford. At age 23 Scott had attracted notoriety in March 1989 with an installation in Chicago called What is the Proper Way to Display A U.S. Flag? which invited viewers to write comments on a ledger while standing on the flag. Protests and bomb threats followed, and lawmakers passed the Flag Protection Act of 1989, which included in its list of forbidden acts having the flag on the ground. Dread Scott and others protested by burning a flag on the US Capitol steps and were arrested. Ultimately, the Supreme Court struck down the law as a violation of free speech.

Back to Prospect Park in 1994: Dread Scott submitted a piece titled El Grito for the exhibit curated by Benson for the reopening of the Grand Army Plaza Arch, Trophies of the Civil/War(s). It is not clear if Parks or the Alliance were aware of Scott’s reputation or knew that he had work in the exhibit. That would all change in June.

Dread Scott describes his piece: “El Grito is a collaborative installation produced with Joe Wippler that envisions a future civil war in the US…. The installation consists of: a massive graffiti mural of 9-foot-tall armed men and women. In the flames of their guns the theme of the artwork is announced: It took a civil war for Black people to be changed from chattel slaves to wage slaves…We must fight another civil war to end this system which enslaves the planet. On either side “eternal flames” are lit. Real Molotov cocktails made from beer bottles. Across the stairwell are life-size cop and National Guard uniforms (stretched on headless mannequins) bleeding and dying. A bullhorn protrudes from the wall; a woman announces:

Sisters and brothers, we aren’t alone. Yesterday, comrades in Los Angeles, Chicago and DC launched an insurrection. Today, we control several other projects, ghettos, and neighborhoods in this city and the party has led armed uprisings in cities across the country. This is different from the riots and rebellions of the past year. This is a nationwide insurrection and for the first time in the history of this country, we have a real chance to go for power, to defeat their armed forces, to overthrow their government, and put the oppressed in power…We are fighting for a world where no handful of ‘haves’ sits on top of us have-nots. No more whites oppressing other nationalities. No more men oppressing women…” https://www.dreadscott.net/portfolio_page/el-grito/

To view a video of the installation, click this link: El Grito.

After a description of the exhibit appeared in the Park Slope Paper on June 10th, some began to protest the use of public funds to display what some described as a glorification of the murder of police officers. On June 18th Staten Island Borough President Guy Molinari released a statement condemning the exhibit and supporting efforts to shut it down. Molinari explicitly approved of the actions of Curtis Sliwa, the founder of the Guardian Angels, a volunteer, red-beret-wearing crime watch group who patrolled the subways. Sliwa and four other Guardian Angels were arrested on June 19th for trying to deface El Grito with spray paint.

“An audio voice tells you that it’s time to pick up your guns and kill the pigs,” Mr. Sliwa said, explaining that he had complained to various city and state agencies about the work several weeks ago. “Nothing was done, so we went there with cans of paint and rollers prepared to paint over it, and we were arrested.”

around 350 members; in 2021 Sliwa ran for mayor as a Republican

Since the El Grito installation, ultimately, was on the property of the NYC Parks Department, both Parks and the Alliance came under fire, forced to defend free speech while disavowing El Grito’s perceived message. The fallout resulted in the exit of curator Melissa Benson, and no Alliance staff person has held a position that refers to visual arts since then.

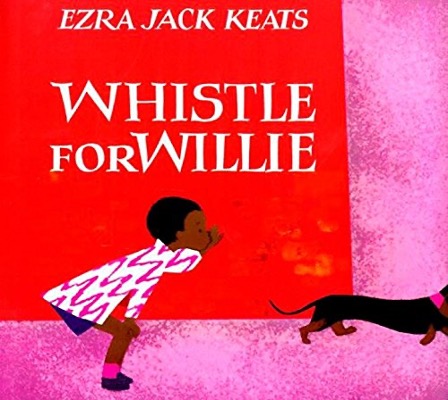

But that was not the last of art in Prospect Park. In 1997 works by Brooklyn sculptor Otto Neals were displayed in the Arch gallery in conjunction with the installation of his Peter and Willie sculpture for Imagination Playground. Cast bronze versions of Peter and Willie, a boy and dog who appear in children’s books by Ezra Jack Keats, are grouped with a park boulder excavated during a park construction project.

In 1999, 25 artists including Otto Neals had artwork in the Arch exhibit Rhythm, Pattern, Color: The Drum.

An exhibit in 2002, In the Spirit of the Trees, featured Otto Neals and also Deenps Bazile, another Brooklyn self-taught sculptor with ties to Prospect Park. In the 1980s, soon after his move from Haiti to the U.S., Bazile carved figures into a large stump near the lake. Bazile was, he said, inspired to carve a large human head, two small human faces, a lion and a legba into the stump, creating a potomitan, a conduit for Vodou spirits. Its presence turned the area, which became known as Gran Bwa, into a focal point for the Haitian community.

The stump, a victim of vandalism, is no longer there, but Gran Bwa is very much alive, brought into being by the power of art.

Note: Mariela Bisson, “The Art of Prospect Park”, in Public Art Review (Spring Summer 1991).