Frederick Law Olmsted and his successors are well known for their development of city parks and park systems, but they also made lasting contributions to the National Park Service (NPS). Olmsted’s 1865 Preliminary Report upon the Yosemite and Big Tree Grove, set a prophetic vision for parks and scenic reservations as a tangible illustration of the principles of equity and benevolence, and the fundamental role of government to provide access to the restorative value of natural scenery. It also made the case for harmonious public access that does not create an artificial character. In other words, landscape architecture could provide the means for thoughtful design for Americans to experience these national treasures.

The National Park Service was formalized by an act of Congress in 1916, and it took many years for the stars to align to make this possible. Olmsted’s Yosemite report, greatly influenced Horace McFarland, president of the American Civic Association (ACA), who were actively promoting the protection of natural scenery. Passage of the 1906 Antiquities Act and bills proposed in 1911 to create a federal park bureau, helped set the stage. McFarland, Olmsted Jr. and conservationist Stephen Mather (who became the first Director of the National Park Service) played key roles in successfully navigating the political landscape that finally resulted in the passage of the 1916 Organic Act, formally establishing the National Park Service.

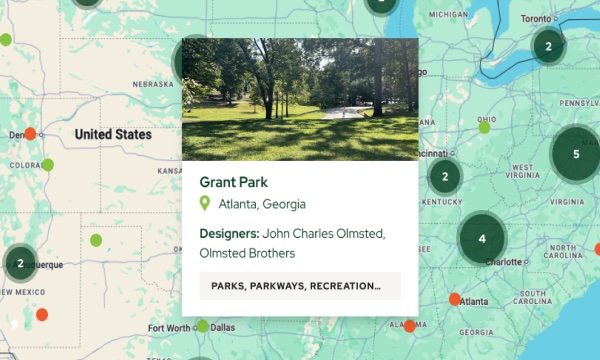

Other members of the Olmsted firm also contributed to the effort. The American Society of Landscape Architects formed in 1899 with John Charles Olmsted as the first president; in 1915, they created a Committee on National Parks and Forests and in 1916, the annual conference held in Boston focused on national parks with papers presented by Olmsted, Jr., Warren Manning, James Sturgis Pray, and Henry Hubbard. They called for an organized and systematic approach to the development of a national park system to replace the existing management of the 49 national parks and monuments existing at the time. Following the ASLA conference and working closely with McFarland, Mather and others, Olmsted Jr. crafted the statement of purpose in the Organic Act that remains as important today as it was a century ago.

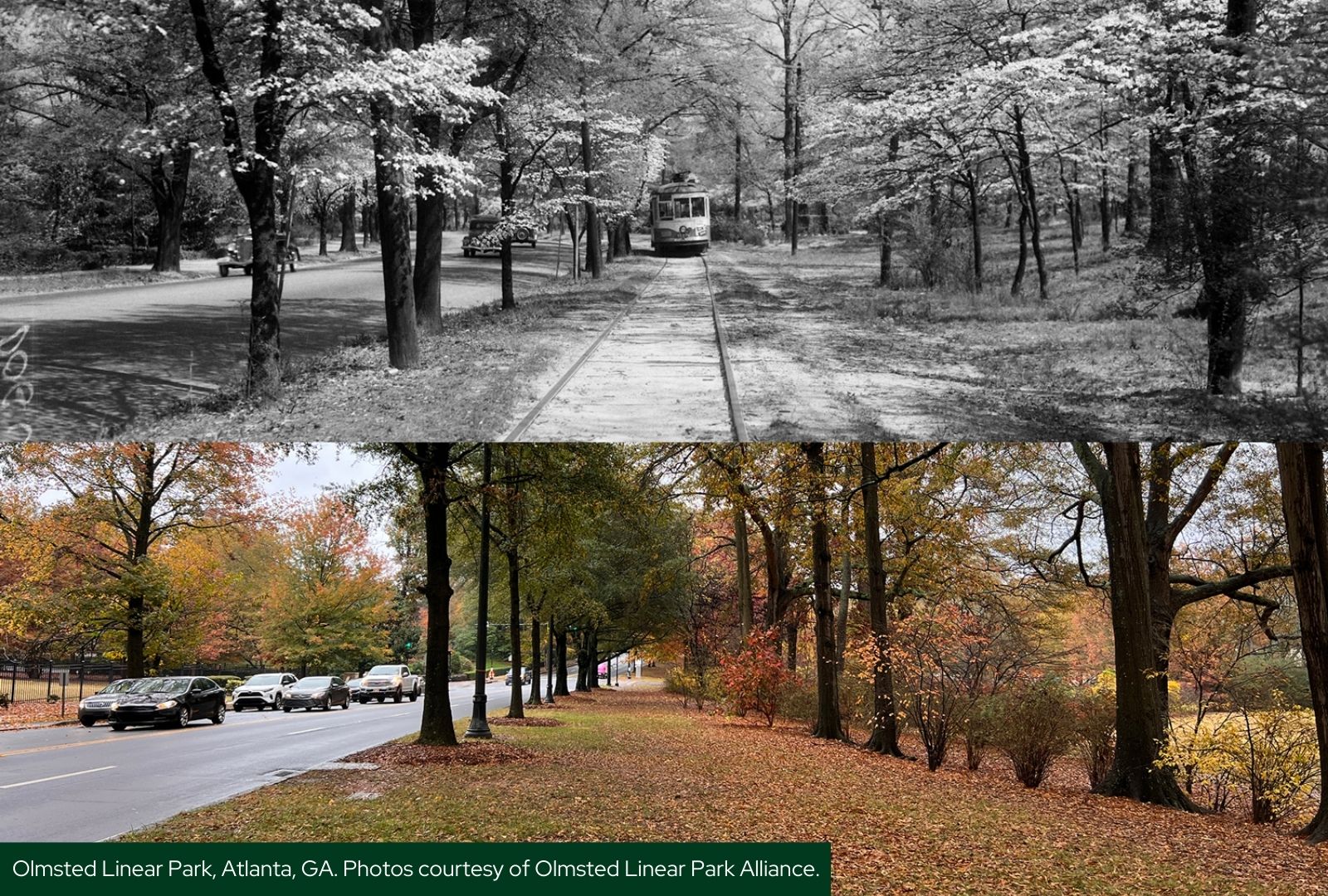

It is not possible in this short essay to enumerate how the Olmsted firm, particularly Olmsted Jr. contributed to the planning and design of national parks and the development of the National Park Service as a federal agency. The relationship between Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and the NPS is a complex one that involved a variety of roles with projects that often overlapped or multiple sites covered under a single job number. Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.’s earliest contribution was as a co-author of the 1902 McMillan Plan and a designer of many of the public landscapes of Washington, D.C., which were transferred to the NPS in 1933. As a result, the Fine Arts Commission is one of the largest jobs in the Olmsted portfolio.

For over forty years, from 1916 until 1953, Olmsted Jr. provided a wide range of support to the NPS, including the evaluation of potential new national parks. He was devoted to Yosemite National Park and in 1928 was named to its Board of Expert Advisors, a position he held intermittently until 1953. He undertook several planning and design projects, mentored key agency staff and leaders and advised on issues at many national parks and monuments. One of his primary roles was as a design peer reviewer for NPS staff. Behind the scenes, in 1932 he led a reconnaissance trip to the Everglades that helped to overcome opposition from Robert Sterling Yard and the National Park Association (APA) to a potential national park.

A few examples of design projects by the Olmsted Brothers include the motor road at Acadia National Park, Maine (1930s) and the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial at Great Smoky Mountains National Park (1938 by Henry Hubbard). Historic sites such as Fort McHenry in Baltimore (1916-1917 by P.R. Jones), Washington Square in Philadelphia (1913 by Percival Gallagher) and Fairsted (1883-1979) in Brookline, MA became part of the national park system well after the Olmsted design work was done. Olmsted Jr. wrote several planning documents such as his 1929 report on the Kilauea section of Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park. The largest NPS planning project is the Colorado River Basin Recreation Survey (by Olmsted Jr. 1941-1950) that covered a massive land area in California, Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Wyoming; it is this project that gives credence to the Olmsteds’ involvement in every state in the nation. As NPS “Collaborator” beginning in 1943, he coordinated interagency agreements and negotiations over water rights, dams and highways affecting national parks.

To help increase understanding of the importance of the Olmsteds in the creation of the national park system, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site commissioned a recent Historic Resource Study through the Organization of American Historians, “The Olmsteds and the National Park System” by Ethan Carr, Rolf Diamant and Lauren Meier. It provides a broad view of the contributions of the Olmsteds to the development of the NPS. A deeper dive into Frederick Law Olmsted’s Yosemite report by Carr and Diamant will be available in early 2022 from the Library of American Landscape History – Olmsted and Yosemite: Civil War, Abolition, and the National Park Idea.