I was lucky enough to grow up in a designed landscape in Weston, Massachusetts, that showcased the talents of Olmsted, Ernest W. Bowditch and Charles Eliot, so my hundreds of bike rides on the sinuous narrow lane amid quiet fields and over a vociferous stream and hundreds of forays on forest trails left their mark. Falling in love at age ten with Stonehurst, a beautiful and primal estate belonging to an aged cousin years before I knew Richardson was the architect, let alone Olmsted the landscape architect, confirmed my environmental orientation. While attending a secondary school on a campus that had originally been another Richardson-Olmsted designed estate, I began to read about the architect and discover the term landscape architect.

Long before China became a draw, in the years of jet travel in the mid 1960s linking Americans to Europe with its cafes and plush parks, a critical mass was forming, and it was critical of our incomplete streets and long neglected public spaces and parks, like shabby Times Square, drug infested Bryant Park, and derelict Central Park, enough to launch a quiet revolution in park urbanism at home. I became fascinated with the roots of New England commons and greens in the “open field” agrarian system of medieval England and France—greenspace before its time. And ecologist Garret Hardin’s impassioned Tragedy of the Commons lamenting the loss of collective stewardship for our wider environment was calling a new generation of environmentalists to action.

My undergraduate thesis pointed to me to a career as a landscape architect interested in the public realm. In the same year that kids my age in China were being sent to the countryside to clear their thoughts while engaging in hard manual labor, with hardly a moment to think about landscape anything, I studied public access to the reservoirs and aqueducts of the metropolitan Boston public water supply system that extended halfway across Massachusetts. What I was envisioning was a de facto park system scores of miles long.

While China could ill afford to struggle to save its environment, although the real pollution lay in the future, the West was becoming concerned with environmentalism. In 1969, Greenpeace was founded, in 1970 the first Earth Day was held and the Environmental Protection Agency was founded. As the environmental movement gathered momentum, the field of landscape architecture attracted diverse interests and talents. Some still preferred to focus on the design of outdoor space as an art-form uniquely wedded to natural processes. Others loved the emerging holistic, integrative view of analyzing, planning, and designing a “landscape” as large as a region. Still others looked to focus less on natural systems like watersheds than on urban systems like transportation, more grandly the new interdisciplinary specialty called urban design. Preservation and design were now side by side, on a continuum. Less easily mapped than the natural systems were the social systems that elicited the rousing writings of Jane Jacobs and William Holly Whyte. It was all fascinating, as I embarked on the three-year program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) studying toward my Masters in Landscape Architecture. The world’s oldest school of Landscape Architecture, founded in 1900, predated China’s oldest program, at Beijing Forestry University, by over fifty years.

The Trust for Public Land founded in 1972 joined the Nature Conservancy, formed in 1951. Open space advocacy in the US had come a long way since the apathetic era of the 1950s and 60s when parks earned so little respect that the neglected ones, shabby, obsolete and rife with vagrants, were not even considered as part of urban blight. Now urban open spaces joined their country cousins in gaining a newfound respect.

Again and again, I was drawn to urban public open space. I worked for Genie Beal, then head of the Boston Conservation Commission and later a beloved open space advocate, on a greenway corridor plan for land parcels straddling Boston and the abutting town of Brookline. A team project culminating in a publication called Olmsted’s Park System as Vehicle in Boston (1973) anticipated the emerging zeitgeist. Boston’s park system had already long been affectionately called the Emerald Necklace. Landscape preservation was evolving into a discipline in its own right. I took on Franklin Park, the largest gem of the Emerald Necklace. The project was ahead of its time. So was keypunching land data cell by cell, covering a region in a coarse grid, anticipating GIS to come. Likewise, the best-selling book in landscape architecture, Ian McHarg’s Design with Nature, championed an alternative to keypunch cards, the overlay system, the layering of which anticipated computer-aided-design (CAD) files to come. If this was our revolution, so be it, I was a proud revolutionary. In the fullness of time, the more apt term came to be innovator. No use of force, just logic. No chance of being boxed in a jailcell for “thinking outside the box” indeed. But old habits, even in a non-repressive, non-authoritarian society such as ours, still died hard.

The revival of all things Olmsted rode the crest of the environmentalism wave. By 1980 in the run-up to the dedication of Olmsted National Historic Site in Brookline in 1981, I joined the newly formed National Association of Olmsted Parks that brought together park advocates from all over the country, since that was where Olmsted’s parks were. Friends groups formed to raise funds to supplement stingy public maintenance and capital budgets, and assist in envisioning richer programs and activities for parks first conceived now 175 years ago. Olmsted continued to speak to us because he intuitively knew truths that were made explicit by psychologists a century after Central Park.

At Brown Richardson & Rowe, in 2006 at last I had my chance to do something about Boston’s parkways, greenway corridors with sinuous roads winding though them, a form and a term invented by Olmsted that had spread across the country thanks to the National Park Service, and Robert Moses. In Boston’s parkways, commuting cars had taken a heavy toll on a system first conceived in the horse and buggy era for recreational drives. The Historic Parkway Preservation Treatment Guidelines that I authored for the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation accommodate the multimodal world we were now in, while safeguarding the special character of these scenic roads.[1]

In 2006 I joined forces with a Shanghai-based design firm. My year with AGER took me all over China and revealed a scale and rapidity of urbanization that I could barely have imagined back in the U.S. I found myself using the term squandering of precious resources. I lectured at symposia and conventions. And I told myself to stop the whining about anything we Americans endured back home.

After I opened the company’s first overseas office in Boston in 2008, indeed the first bona-fide office of any design firm in the US, I found myself drawn to the idea of writing a book on urban public space best practices. And it would have guidelines. I wanted nothing important to get lost in translation, so my vision for Cities with Heart included the original English text and the Chinese translation side by side—and Central Park on the cover. The company had hired a Shanghai-based bilingual communications specialist who not only understood my English, but educated me on the differences in exposition, both as to logic and to clarity. When I had met her on a company trip to Shanghai World Expo in 2010, she mentioned that she had been captivated with Thoreau’s Walden since she was a fifteen-year-old schoolgirl living in a mountain village a few hours outside central Qongqing. She loved Transcendentalist writers like Emerson and Fuller. I was stunned. That she found Thoreau in such a place spoke volumes about where our world was heading, and it was a good place. It was my pleasure to make sure she saw Walden, preserved for all time in its greenspace unsullied by private development (thanks to Don Henley of the Eagles).

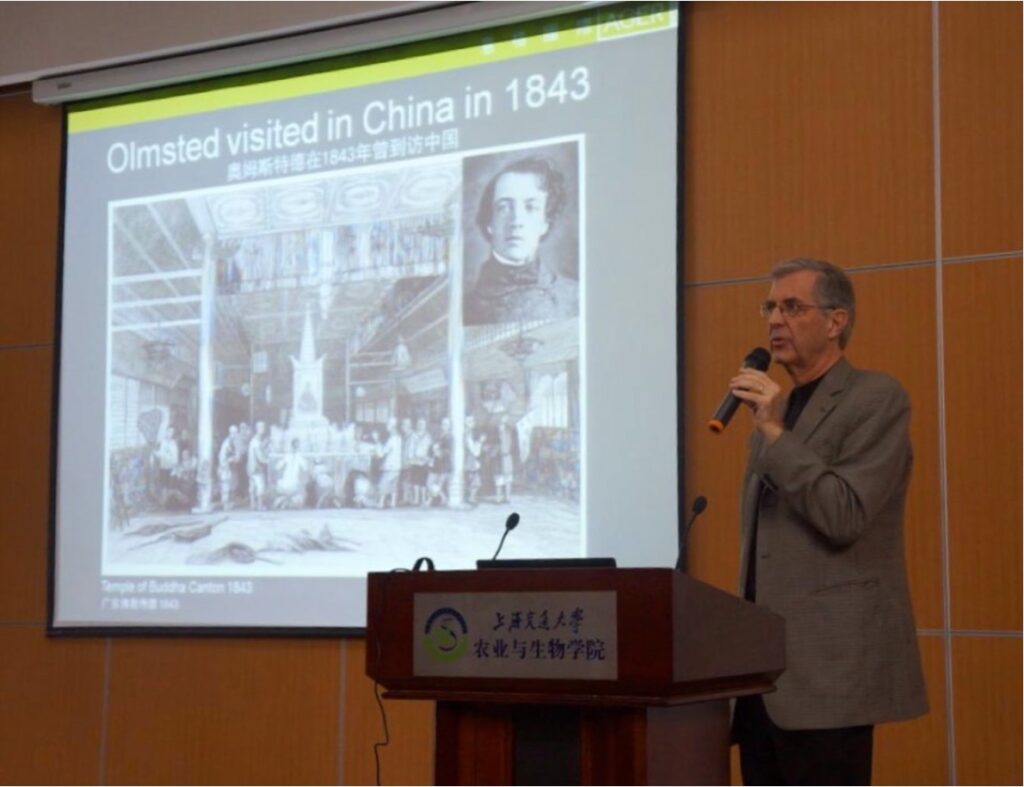

My book tour for Cities with Heart took me to four cities—Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu and Guangzhou, four among the hundred cities of over a million in China, many of which were not yet cities with heart. If Olmsted’s Central Park already spoke to the Chinese as a forerunner of “people’s parks” to be found in many Chinese cities, they were even more delighted to learn that in 1843, Olmsted himself had come to China as a young man, a common sailor, years before he took up landscape architecture, and was so moved by the kindness extended to him by the ordinary people of Guangzhou who welcomed him into their workshops, homes, temples and gardens that it helped inspire his vision of parks “unreservedly and forever the people’s own.” “The establishment by government of great public grounds is,” he wrote later, “…justified and [must be] enforced as a public duty,” not something to be left to chance in the marketplace. He had recognized the greenspace imperative way ahead of his time.

Over my career, again and again I had returned to open space projects, until I could no longer deny that together they had formed the open space system running through my life, all connected, and all underlying my evolution from childlike delight in nature to the greenspace imperative, and that Olmsted was behind it all.

[1] Historic Parkway Preservation Treatment Guidelines, Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Division of Planning and Engineering, March 2007, http://www.mhd.state.ma.us/downloads/manuals/HPguidelinesfinal.pdf

Visit author Thomas M. Paine’s website to learn more about him and watch videos from Stonehurst’s Olmsted 200 celebration in 2022.