Resources

Lucy Lawliss, Caroline Loughlin and Lauren Meier

Researching an Olmsted Landscape

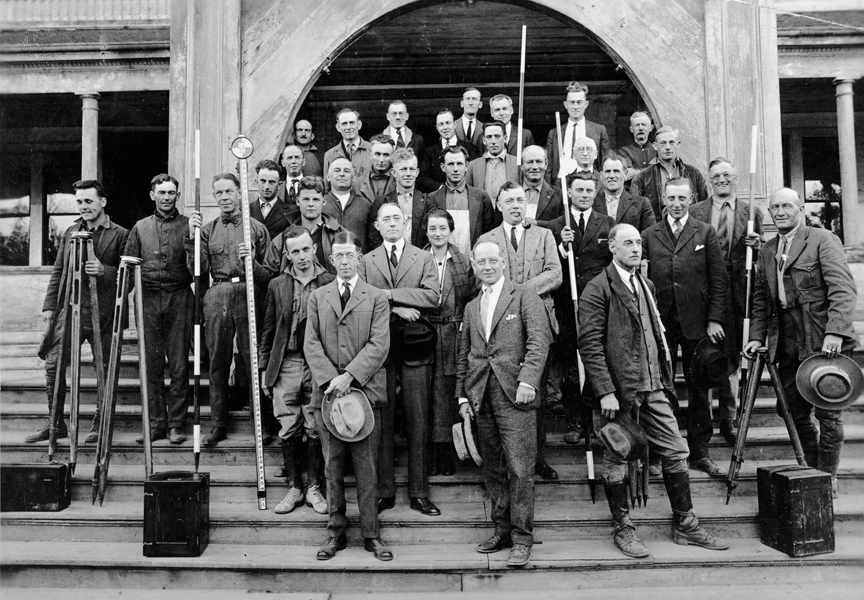

Research is fundamental to understanding the evolution and significance of a historic designed landscape. It can be done for purely academic reasons but more than likely it is undertaken to guide treatment and management decisions for a particular property. These decisions should be grounded in a full understanding of the original design intent, the project’s as-built realization and subsequent additions or changes. Researching a landscape for the purposes of treatment includes documenting the development of built features, the use of specific materials, vegetation—both original and planted—and the spaces that make a particular landscape distinct and important. Thus, if the goal is to identify and preserve significant elements as well as the overall character of the historic landscape, the successful implementation of treatment decisions will depend on the adequacy of the research effort.

Designed landscapes associated with the work of the Olmsted firm are important for many reasons, including design, execution, contextual relationship to similar properties, use—past and present—and their place in the local, regional or national environment. Research is essential in determining the historical significance as well as the integrity of the existing landscape. The following steps recommend a tested approach to researching an Olmsted-designed landscape.

Defining the Research Scope

For anyone undertaking landscape research—landowners, managers, park officials and design professionals—it is important to define the scope and objectives for the research project. For example, if the goal is to restore a designed landscape to its height of activity or period of significance, the level of research must provide sufficiently detailed information to guide the restoration effort. Therefore, once the scope and objectives of the project are established, the researcher can define research questions both to direct the study of sources and to shape the final outcome. Considering the following questions will help determine the information needed to meet the project’s goals and objectives.

Things to ask about an Olmsted landscape include:

• When and why was the property selected/purchased? Who chose the property?

• Who are and have been the owners of the property? Did they or others place restrictions on its use or treatment? If so, what are they?

• What names have been given the property (historically, colloquially)?

• Who hired the Olmsted firm? Was there a prior relationship with the firm?

• What was the land’s condition or how was it used before the involvement of the Olmsted firm?

• Who were the intended users and how was this accomplished? (What was the design intent?)

• What was the extent of the design effort of the Olmsted firm and to what degree was it realized?

• Who were the subsequent designers, landscape architects and others involved after the Olmsted firm? Are they known locally, regionally or nationally for their work?

• What remains from the original design/construction? What is its condition?

• What is the overall condition of the landscape? Has it been in continuous use or abandoned?

• Who actually used (uses) the landscape and in what way?

• How will the property be used when this project is completed?

Identifying Sources of Information

• The second task in researching an Olmsted landscape is determining how and where to find information needed to answer the research questions. There are a number of local and national sources described below.

Local Sources

For individual landscapes, it is important to check local resources first. Places to look include:

• Historical societies, public libraries, garden clubs;

• College and university archives or libraries;

• Municipal archives (parks departments, departments of public works, water and sewer departments, court records);

• Newspaper files and archives;

• Sources cited in footnotes, picture credits and bibliographies of local histories;

• State historic preservation offices.

Specific things to look for from local sources include:

• Official documents: annual reports, minutes and journals of public agencies or commissions, construction contracts and maintenance records, census records, municipal ordinances and charters, state laws and constitutions, wills, real estate deeds;

• Secondary Sources: histories of the municipality, city, state and region; essays; biographies

• Newspapers and periodicals: articles, photographs, editorials, letters to the editor, obituaries

• Unpublished materials: diaries, letters, catalogs of local plant nurseries, seed catalogs

• Visual records and associated documentation: maps, plans, drawings and sketches, photographs, postcards, plant lists

• Transcripts or taped materials of interviews and oral histories

• National Register of Historic Places nominations that describe the building, structure, site or district.

National Sources

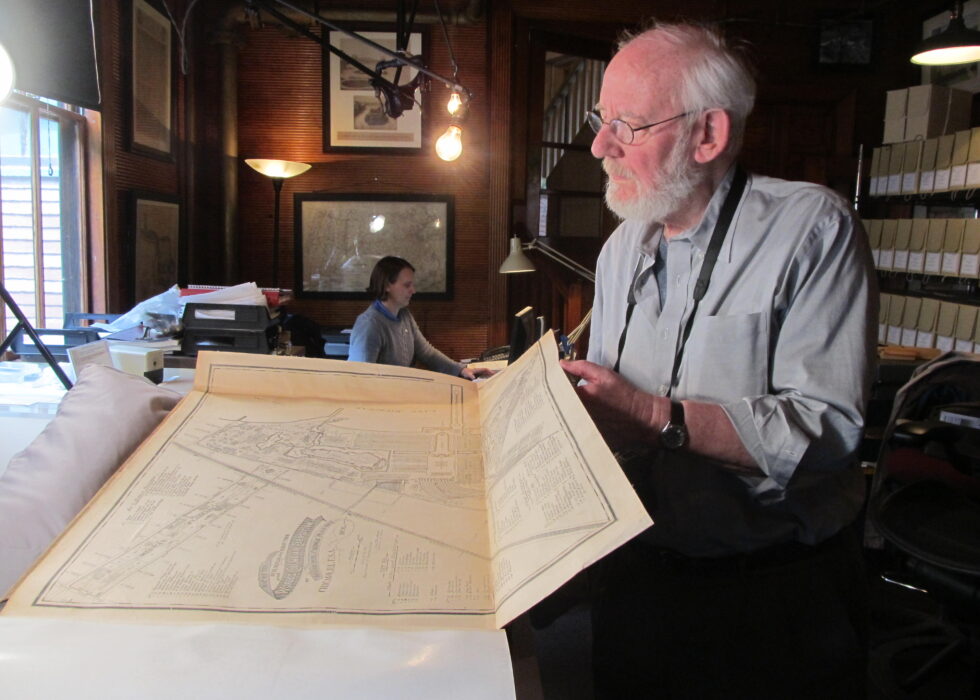

There are two primary national sources for information about Olmsted firm projects: Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site and the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. The National Park Service manages the Olmsted Archives as part of the museum collection of the Olmsted National Historic Site (NHS). The Archives include plans, photographs, plan index cards and planting lists, each associated with a job number assigned by the firm.

The other national repository is the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. This source contains most of the firm’s written correspondence and administrative files, which support and explain the drawing files. The manuscript collection can be connected to plan and image records in the Olmsted Archives by job number.

Before visiting either of these sources, a researcher can determine a project job number along with preliminary project information by consulting this Master List of Design Projects or by using the Olmsted Research Guide Online. Use of these finding aids is a critical step and saves time and expense by providing information that will facilitate contact with either national repository. With the job number(s), and an indication of the quantity and type of materials available, the researcher is ready to consult with the Library of Congress and Olmsted NHS to get a clear understanding of what these sources have and how to access the materials. A trip to both institutions is highly recommended if material of interest is confirmed. Consulting these primary sources is the only way to establish the design and intent of the specific job(s).

Olmsted Research Guide Online (ORGO)

The Olmsted Research Guide Online is an online database of archival records related to the work of the Olmsted firm. ORGO is an expanded list of Olmsted job-related documents — both those at the Library of Congress and those at Olmsted NHS.

Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

The National Park Service preserves and protects the Olmsted firm’s archives at Olmsted NHS and makes items available for public use with assistance from park staff. Prior to making a research request, individuals should review the information contained in the Master List and in ORGO to determine the job number and what relevant information is housed at Olmsted NHS. Once this is established, researchers can contact Olmsted NHS to schedule a research appointment or to request materials online.

Library of Congress

The Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress contains collections of historical papers that support scholarly work in political, cultural and scientific history. This includes two important collections related to the work of the Olmsted firm: the Frederick Law Olmsted Papers and the Olmsted Associates Papers, which were acquired by the Library of Congress in several groups from 1947 to 1996. Detailed finding aids for both collections are available online. Individual reels of microfilm, or the full set, may be purchased from the Library of Congress or borrowed through interlibrary loan. The Manuscript Division also houses the papers of Laura Wood Roper, Frederick Law Olmsted’s first biographer.

Selected Other National Resources

The John Charles Olmsted Collection at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in Cambridge, Massachusetts, contains letters, correspondence files and material related to Olmsted firm business or professional associations, as well as family papers, memorabilia and photographs from the papers of John Charles Olmsted (1852–1920). John Charles Olmsted was the nephew, stepson and business partner of Frederick Law Olmsted.

The Archives of American Gardens managed by the Smithsonian’s Horticultural Services Division contain documentation for more than 5,500 gardens and landscapes, some of which were designed by the Olmsted firm. This collection includes historic glass lantern slides and 35mm slides donated to the Smithsonian by The Garden Club of America, as well as photographs, plans and papers documenting the work of several important landscape architects, including selected works of the Olmsted firm.

Using Sources

While researchers like to use sources with confidence, some caution should be taken before making assumptions related to the information contained in these sources. Design plans represent the artistic vision of the individual or firm, not necessarily the project as it was implemented. Thus, plans should be viewed in concert with historic photographs, correspondence, planting order lists, construction records and, if possible, as-built drawings to determine the built form of the landscape. Detailed inventory of the existing landscape conditions may also reveal information about the execution of the design.

Non-academic publications (including newspapers and memoirs) and personal interviews should be examined for possible bias and misinformation. While they can be informative in communicating popular views at a specific time, they may be unreliable for events distant in time, and thus need to be corroborated through the use of other sources. Often limited involvement of the Olmsted firm in the historic period gained prominence over time as the reputation of Frederick Law Olmsted and the successor firm grew. Design work accomplished by other professionals often gets attributed to the Olmsted firm if the Olmsted firm was involved at any time in the property’s history. The work of Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. is often misattributed to the father. Photographs may be misidentified as to date and location. Colors in hand-tinted photographs are unreliable. Even printed material on period postcards may be incorrect and should be verified using other sources.

Using Research for Planning and Design

Research should be the foundation for planning and guiding treatment work on the historic landscape, including new design work in the landscape. Without research, the historic design intent as well as the features, materials, character and landscape spaces that contribute to the significance of the property cannot be known or fully understood. The National Park Service has developed guidance in preparing Cultural Landscape Reports, which can serve as an effective methodology for landscape planning and design in an Olmsted landscape. The scope of a Cultural Landscape Report can be modified to fit the scale, complexity and budget of the project (see Defining the Research Scope).

Four steps are essential to preparing a Cultural Landscape Report and all should be undertaken before making physical alterations to the historic landscape, so that historic features and the overall character are not inadvertently lost or damaged. Each of these steps provides information necessary to the success of a project.

• Site history – documents the physical evolution of the landscape;

• Existing conditions – records the current condition of the property with site plans and a narrative description;

• Integrity and significance – analyzes extant historic features and relevant historic contexts and establishes the significance of the landscape;

• Treatment — recommends physical design and work on the landscape necessary to meet the owner’s needs and objectives, consistent with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards.

Additional Resources

Here are a few more places where you can find materials by and about Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux, John Charles Olmsted, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and the Olmsted firm.