In 1846, seven-year-old Frances Willard and her family moved by prairie schooner from New York nine hundred miles west to a farm in southeastern Wisconsin. Frances would later write that among other journals that came to their isolated farm was The Horticulturist, edited by “that artist of landscape gardening, A. J. Downing [(1815-1852)], whose death by a steamboat accident upon the Hudson River smote us almost like a personal bereavement.”[i] The Willard family was one of a multitude of Americans who embraced Downing as the author, editor, horticulturist, and landscape gardener who guided the young nation’s taste in all things rural.

In 1846, the same year that the Willard family made its way west from New York, Downing was living in Newburgh, a village on the west bank of the Hudson River sixty miles north of New York City. In July of that year, the first number of The Horticulturist was published.

Luther Tucker, proprietor of the New York agricultural journal The Cultivator, had wisely sought as editor the 30-year-old author of the best-selling Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening of 1841, Cottage Residences of 1842, and Fruits and Fruit-Trees of America of 1845. The Architecture of Country Houses published four years later only enhanced Downing’s reputation.

Andrew Jackson Downing was born on October 31, 1815, in Newburgh, New York. Downing was remembered as a promising youth and uncommonly bright for his years; he showed an early interest in botany, mineralogy, and entomology. He was fortunate in the area’s great botanical variety; more native species of trees could be found in the Hudson Valley than in the whole of the British Isles.

The future artist of landscape gardening began his career as a nurseryman. In 1831, Downing joined his brother Charles in the nursery business, which they named “C. & A. J. Downing Botanic Garden and Nursery,” and he quickly assumed a position of leadership in the New York Horticultural Society.

Ten years later, at the age of twenty-five, Downing published his Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening Adapted to North America in which he outlined for his readers how American landscape gardening differed from that of the Old World. Although there were plenty of British works on the subject, they were predicated upon a climate, society, income, and cost of labor wholly different from those in the United States. Downing recognized “a great want of something . . . felt in this country and great groping in the dark in the absence of it.”[ii] This need for native-born books was concisely explained by Downing: “No two languages can be more different than the gardening tongues of England and America.”[iii] From practices in the flower and vegetable gardens to the method of transplanting trees, Downing noted that the bad words of English gardening were damp and lack of sunshine, those of America, drought and hot sunshine.

Nevertheless, for his theory of landscape gardening, Downing borrowed ideas from the Old World—especially Britain. The major concept was that landscape gardening should be considered a fine art. Downing was particularly indebted to the Scottish-born landscape gardener John Claudius Loudon, who sought to change the long-held notion that the object of landscape gardening was to copy nature. Art should be recognized everywhere in the landscape, Loudon proclaimed, especially in the predominance of exotic trees, shrubs, and other plants over indigenous ones. Loudon originated a landscape style that he named the Gardenesque, which considered every individual plant as a specimen.[iv] Downing initially recognized the Gardenesque as one landscape style but eventually dismissed it as making little sense in a country with such rich indigenous plants. He figured out a method to incorporate America’s native plants while still having the landscape be recognized as a work of art.

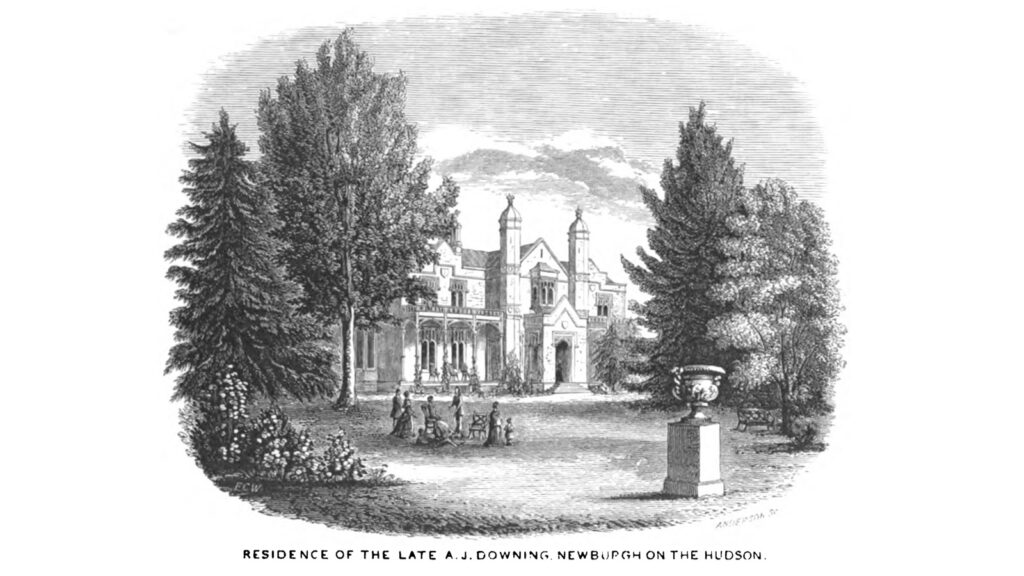

Downing favored the natural style of landscape gardening, which was respectful of nature, as opposed to the geometric style, which imposed order on nature. Downing proposed that there were only two landscape expressions of the natural style: the Beautiful and the Picturesque, and he advised that a landscape was more satisfactory when either one or the other predominated. The two terms were defined by opposing characteristics that Downing assigned to the appropriate American landscapes. The Beautiful was characterized by smooth forms, gradual variation, and round-headed trees. The manor seen in the image is in a style suitable to the Beautiful.

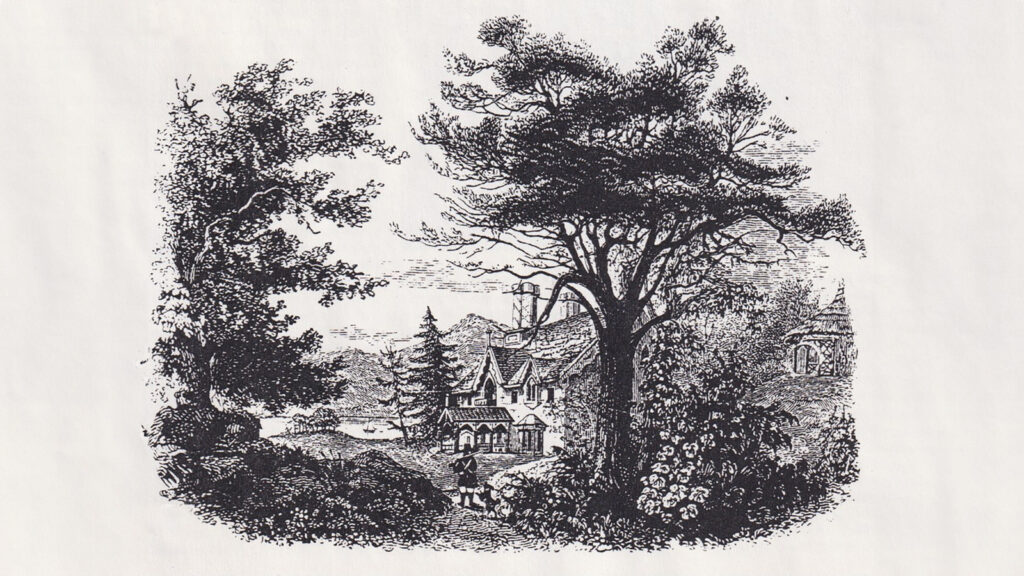

The Picturesque was characterized by rough, irregular forms such as steep, rocky banks overhung with tangled thickets, and conical or half decayed trees. The cottage seen in the image is a fitting match for the Picturesque.[v]

Downing favored the Picturesque over the Beautiful for aesthetic and practical reasons. He spelled out the advantages of the Picturesque in a suitable location such as the naturally wild and bold character of his native Hudson Highlands. With much effect and little art, the raw materials of wood, water, and surface could be economically appropriated. He was careful to explain, however, that in scenery that was naturally flowing in outline, proprietors were obliged to heighten that expression by the refinements of the Beautiful mode.

Downing went on to publish two more editions of his Treatise before his death. He made successive changes to the Treatise to add material of more national interest, and he modified its theoretical framework to take advantage of the expressive potential in America’s indigenous landscape. Nevertheless, this work remained true to Downing’s highest aspirations: to guide country gentlemen—with enough money, time, and taste—in the creation of ideal homes and pleasure grounds.

Downing claimed that the Treatise was adapted to North America; however, the “new starting ground” announced in its second edition was less fertile for American landscape gardening than The Horticulturist proved to be. In The Horticulturist, Downing “spoke American” and offered men and women a message of moderation and simplicity, encouraging them to practice economy, to use America’s rich natural resources wisely yet artfully— to be content with a little cottage and a few fine native trees.

The changes in the 1844 and 1849 editions of the Treatise, when studied in conjunction with Downing’s monthly Horticulturist editorials, show that he moved toward a more realistic assessment of American capabilities and resources, especially America’s indigenous plants, and adjusted his theory and practice accordingly. The monthly format offered Downing the opportunity to articulate his thoughts in a timelier manner then in his books.

Downing embarked on his first and only trip abroad in July 1850. Although too late to influence the Treatise, these travel experiences benefited The Horticulturist because he acquired a firsthand knowledge of England and Paris and a fresh understanding of his own country’s worth. He also acquired a partner. Downing visited the Architectural Association Exhibition in London and was so impressed with the watercolors by an architect named Calvert Vaux, that he asked the secretary of the association to introduce them. Downing and his books and journal were well known in Britain as was his reputation as a horticulturist and landscape gardener. Vaux later remembered that their subsequent friendship was “an instance of the confidence he could always inspire.”[vi] The following day, Downing convinced Vaux to return with him to America.

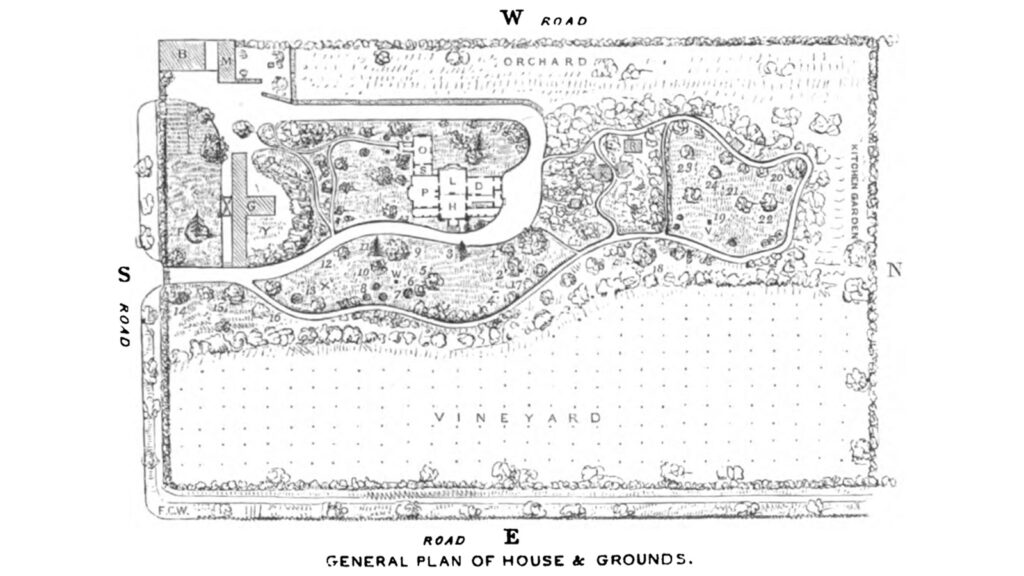

Downing and his wife’s Newburgh home and its surrounding landscape exhibited the ideas put forth in The Horticulturist. The five-acre site was laid out in Downing’s preferred natural style with gently winding pathways which offered carefully orchestrated views of the Hudson and distant mountains. Secluded spots with rustic benches and covered structures were integrated into the farthest reaches of the grounds. For almost two years, Vaux lived in and came to understand the beauty and benefits of this type of landscape.

In those years, as well, Downing was writing editorials on subjects that he surely discussed with his partner. The editorial “The Neglected American Plants” of May 1851, likely shaped Vaux’s ideas on landscape gardening appropriate for American conditions. A distinct change in the tenor of Downing’s commitment to American plants occurred after his return from Europe. Seeing American plants away from home increased Downing’s awareness of his country’s indigenous treasures. He bemoaned the fact that it was rare on an American country place to see more than three or four native trees, and rarer still to find any but foreign shrubs. He condemned nurseries that did not stock the native tulip tree, sassafras, or pepperidge. While praising the unrivaled beauty of these trees, he also offered practical reasons for their superiority: all were freer from insect attacks then a dozen other favorite foreign trees, and they remained unaffected by America’s hot summer sun.[vii]

American woods and fields, Downing declared, offered ample instruction. He stipulated, however, that the finest pleasure grounds should not precisely resemble woods and fields. He chose the American elm as an example to reinforce this point. He painted a picture of a planted elm standing gracefully on an open lawn. In this situation, the elm had a refinement and perfect symmetry which it would be impossible to find in an elm in the forest.[viii] Thus Downing found a way to incorporate the country’s forests into the basic elements of landscape gardening.

Soon after Vaux’s arrival, Downing accepted a commission to design the estate of Matthew Vassar in Poughkeepsie, New York. This was the first opportunity for Vaux to experience how Downing put his theories into practice. Vaux worked closely with Downing on a number of houses and their grounds in the next two years.

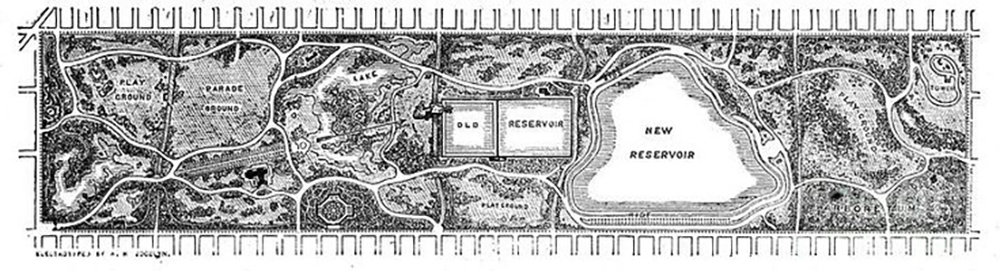

Downing’s opportunity to put his mature theory of landscape gardening into practice and to realize what Vaux recalled as his partner’s “great desire [for] Public Pleasure grounds every where”[ix] was cut short at his death in a Hudson River steamboat fire in 1852. He was in the midst of supervising the improvements to the public grounds of the capital. In 1851, Downing designed the L-shaped area extending from the president’s house along the Mall to the foot of Capitol Hill. This project would have fulfilled two of Downing’s major aspirations: to promote an American taste for public pleasure grounds and to express on a grand scale what he considered the national style— that is, the natural style— in landscape gardening. Certain aspects of the plan found a later expression in the 1858 “Greensward Plan” for Central Park by Frederick Law Olmsted and Vaux.

The 1851 editorial “The New-York Park,” written just a year before Downing’s death, surely shaped Vaux’s thinking and guided discussions during those long nights with Olmsted as they prepared their entry for the Central Park competition. In this editorial, Downing called for a “breathing space for pure air, [a] recreation ground for healthful exercise… [and] pleasant roads for riding or driving.” Most critical was to bring the enjoyment of lovely and refreshing natural beauty to people. Downing painted a picture of overcrowded city streets, hot summers and exhausted New Yorkers longing for escape.[x]

Downing’s vision was thus realized not in the nation’s capital but rather in the city that Downing so eloquently championed in the editorial “The New-York Park.” The 1858 “Greensward Plan” for New York’s Central Park became that “public school of instruction” for everything relating to the tasteful arrangement of parks and grounds. New York’s rather than Washington’s straight lines were “pleasantly relieved and contrasted by the beauty of curved lines and natural groups of trees.” And Olmsted and Vaux’s Central Park, rather than the Washington Public Grounds, still forms “the most perfect background or setting to the city.”

[i] Frances E. Willard, Glimpses of Fifty Years; the Autobiography of an American Woman (Chicago: Woman’s Temperance Publishing Association, 1889): 495.

[ii] A. J. Downing, “American versus British Horticulture,” Horticulturist 5 (September 1850): 249-250.

[iii] Ibid., 250.

[iv] For a further explanation of the gardenesque, see Judith K. Major, To Live in the New World: A. J. Downing and American Landscape Gardening (Cambridge, Mass. and London, England: MIT Press, 1997): 58

[v] Downing’s detailed description of the Beautiful (in the 1844 edition, called the Graceful) and the Picturesque can be found in Ibid., 80-84; 91–96.

[vi] Vaux described the circumstances of their meeting in Calvert Vaux to Marshall P. Wilder, 18 August [1852], Library Company of Philadelphia in Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[vii] A. J. Downing, “The Neglected American Plants,” Horticulturist 6 (May 1851): 201-203.

[viii] A. J. Downing, “A Few Hints on Landscape Gardening,” Horticulturist 6 (November 1851): 491.

[ix] Vaux to Wilder, 18 August [1852], LCP in HSP.

[x] A. J. Downing, “The New-York Park,” Horticulturist 6 (August 1851): 345-349.

Judith Major, Ph.D., is a Professor Emerita of Landscape Architecture in the College of Architecture & Planning + Design at Kansas State University. She is the author of two books: To Live in the New World: A. J. Downing and American Landscape Gardening (1997) and Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer: The Evolution of a Landscape Critic in the Gilded Age (2013). Among other publications, she contributed a chapter entitled “Toward an American Gardening Theory” in the New York Botanical Garden’s Flora Illustrata (2014), which won the 2015 American Horticultural Society Book Award.