Normally, it only takes one finger to push a button.

On a Friday in early October 2024, though, a dozen hands reached out to pile onto the ceremonial switch that would once again get the waterfall in Morningside Park flowing. New York City Parks Commissioner Sue Donoghue opened the ceremony. US Congressman Adriano Espaillat, State Senator Cordell Cleare and City Councilmember Shaun Abreu all gave remarks at the event, along with staff and professors from Columbia University. Friends of Morningside Park President Brad Taylor was the last to speak.

“This is just the start of what should be an ongoing partnership,” he said. “We’d like to build on this partnership, too. I call it AMP, the Alliance for Morningside Park. We can amp it up!” Pointing to other institutions, such as a hospital, that abuts the park, he called for others to join in helping to make other improvements still needed.

And then, the speakers assembled around the big, silver button.

After the count of three, all hands pushed, and after a few moments, rivulets appeared. The satisfying splash of water was met with a sea of applause. A crowd of hundreds had gathered in the park to watch them. The Morningside waterfall is different. More than an aquatic feature, it’s a symbol.

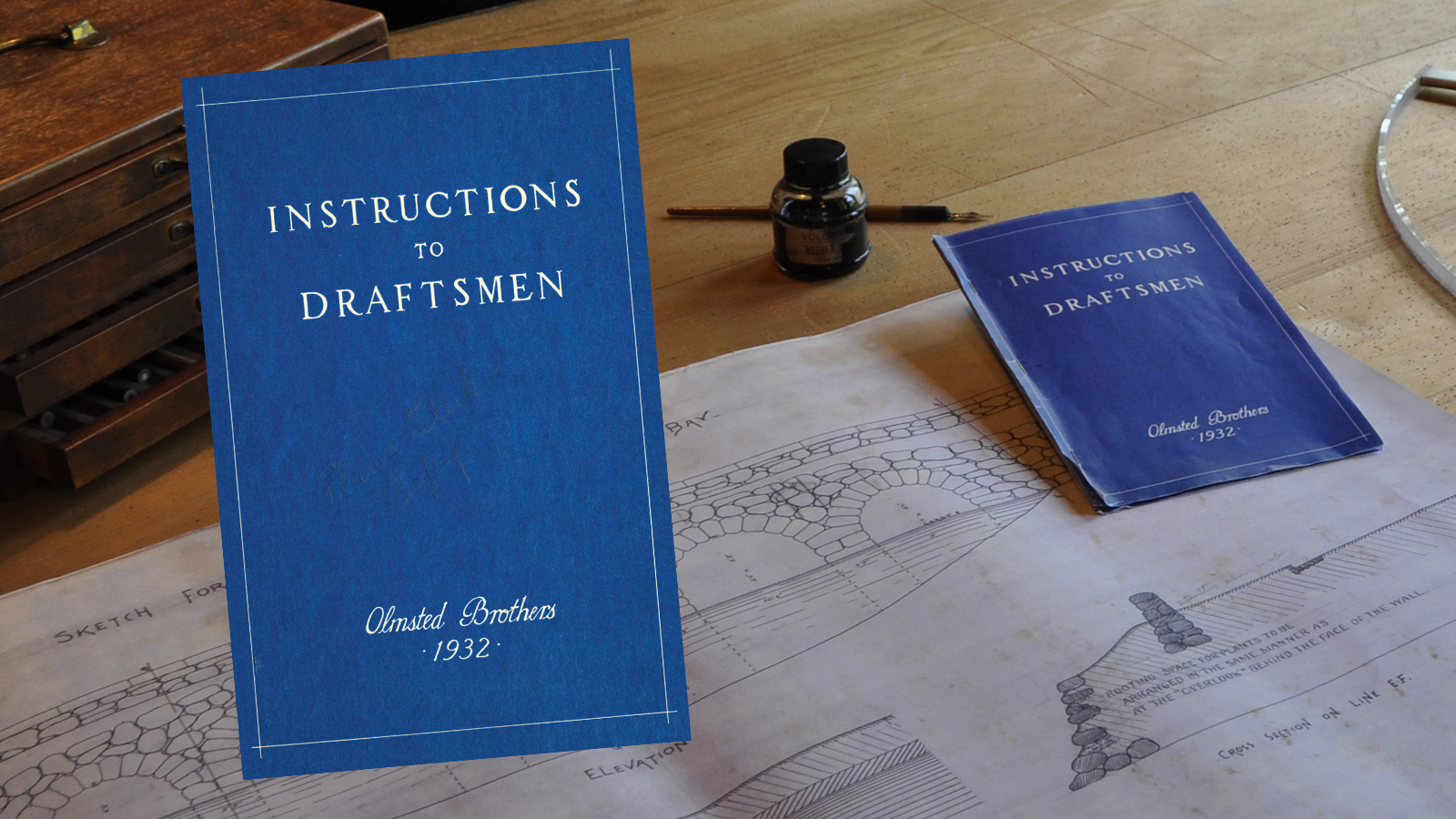

The waterfall in the Harlem park began flowing only after a deep rift threatened to tear the neighborhood and park apart in the 1960s. Back then, the university planned to build a gymnasium in the Olmsted-designed park and excavators started digging. The project was only stopped when students and the neighborhood protested.

For twenty years, nothing was done with the abandoned construction site until another alliance between the city, school and community groups saw the pit turned into a pond. In the 1980s, pumps were installed to make an artificial waterfall. Though not part of Olmsted and Vaux’s original plans, it fit right in and quickly became a favorite park feature.

In 2017, though, the cascade fell quiet. No one was certain what had happened or who was responsible. Then the pandemic hit. Without the stream of fresh water, algae began to spread over the pond, turning it a brilliant green. Blooms like this have become more prevalent due to climate change, and they pose a health threat to children and pets.

In the summer of 2023, the community began pushing again for a solution to their dry waterfall and toxic-green pond. Columbia University stepped forward to offer an interdisciplinary solution, activating a range of talents to address a spectrum of issues. The project is being led by Adrian Brügger, a Columbia professor of civil engineering and engineering mechanics, and Joaquim Goes, a professor at Columbia Climate School.

By January of this year, Brügger’s students had identified the source of the problem— the motor running the pumps had burned out. Working with the city parks department, the students discovered they could replace the motor without needing to replace the pumps. In addition, they designed and built a controller the parks department can use to regulate and monitor the flow. In the meantime, the parks department updated the electricity in the park and made it more resilient against severe climate conditions and flooding.

The Climate School is still working on halting the algae blooms, but the restored waterfall will also help. “It’s not just pretty and bucolic,” Professor Brügger said. “It serves a significant practical purpose, also of, through evaporation, cooling the area, but also aerating the pond.”

When the Columbia Spectator asked the professor in a recent story what the project meant to him, he responded, “The fact that the pond is there is because of the University. So the thing is actually a scar. The pond is a scar of those bad decisions and turning that around and making it actually sort of benefit the community, I think, is a good story. It’s a good ending to a potentially bad story.”

New York State Senator Cordell Cleare agreed in her pre-button pushing remarks.

“Morningside is the park I grew up in. This neighborhood has suffered greatly from neglect to our parks and neglect to other parts of our community. But for many families here, Morningside Park was our Hamptons. This is our getaway. This is where we picnic. This is where we play. This is where we barbecue. To see [these improvements] here; this neighborhood is more than deserving of something like this to come to it.”

Brad Taylor agreed, “To hear the sound of the waterfall again is to hear the promise of a healing force at the heart of our Olmsted park.”