Why are you an Olmsted champion?

Twenty-five years ago, I picked up a biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, and it was one of the best books I have ever read—Witold Rybczynski’s A Clearing in the Distance. The arc of Olmsted’s life intersected with many of the most epochal, transformative and challenging moments of the 19th century. And then I found Laura Roper’s Olmsted biography and later Justin Martin’s Genius of Place. It’s not just Olmsted’s work in park and landscape design, I’m inspired by his thoughts on how to hold a democracy together, his travels and influential reporting through the South during the Civil War, his copious writings on reform principles and his impact on much of how we think and live today. I am also lucky enough to live in the Olmsted-rich city of Portland, OR.

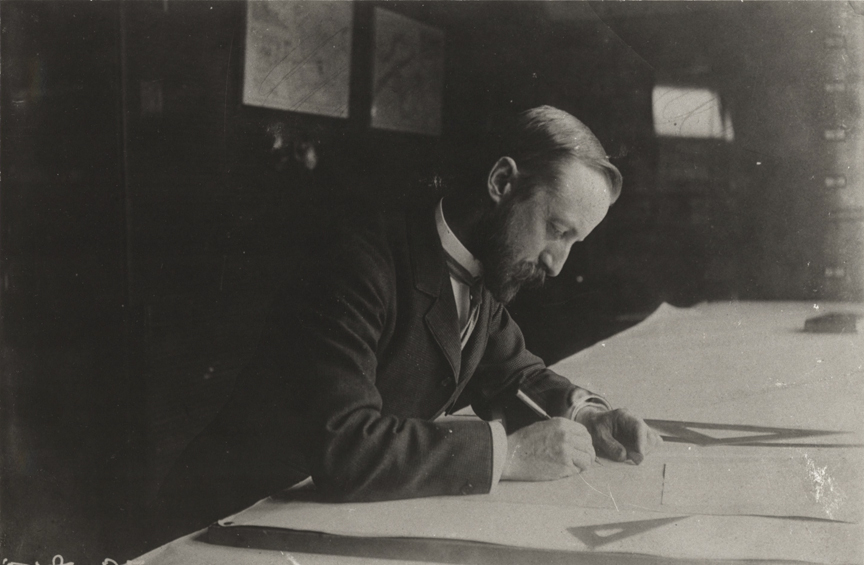

John Charles Olmsted (JCO) was invited to Portland in 1903 by the newly formed Parks Board. He spent three weeks touring Portland by horse and buggy and on foot. The hills surrounding Portland’s west side at the time were still wilderness; the east side was farmland and more forests. JCO saw great opportunities for the young city to plan a city-wide park system while land was still available.

In his 1903 report to the Parks Board, he laid out an elongated, circular plan— much like the Emerald Necklace in Boston. He also included a comprehensive treatise with advice on land acquisition, the qualities of good parks and park systems, park governance, administration and funding. His advice on the latter two was prescient.

In the 1903 Report of the Park Board, JCO writes:

Parks should be kept out at politics not only by not having politicians appointed as park commissioners, but, remembering that “money is power,” by taking the power of making the annual park appropriations from the city government by means of a law giving the park commission a certain minimum and maximum percentage of the total of the assessors’ valuation of the taxable property in the city.

Over many years, Portland Parks & Recreation (PP&R) budget has become a smaller piece of the general fund pie, and over many decades, Parks expenditures on growth, operations and maintenance have become imbalanced— with a resulting crisis in park maintenance.

Last summer, the Olmsted Network called a meeting of park advocates in Portland. What brought on this sudden resurgence of interest in Portland’s public parks, and did this meeting have any lasting impact?

Last June, former CEO of the Olmsted Network Dede Petri visited Portland for a reception at the JCO-influenced Elk Rock Garden, tours in Olmsted-influenced city parks and a meeting Dede called ‘a working session.’ Her visit was planned by a small group of Olmsted advocates who had organized Portland’s Olmsted 200 celebration in 2022. Many volunteer and non-profit park leaders, park advocates, landscape architects and former parks’s leadership attended.

Dede’s ‘working session’ opened with a Q&A from Olmsted Network Board Member and Friends of Seattle’s Olmsted Parks (FOSOP) President Doug Leutjen. Doug shared how the formation of FOSOP had led to the improved maintenance and historic stewardship of Seattle’s Olmsted Parks, and we were inspired by their efforts. Our city parks need champions— groups to advocate for the stewardship of our parks system, much like FOSOP has done for Seattle’s parks.

PP&R has a $600,000 major maintenance backlog, which has grown ever higher over decades. Many of our park assets have already failed: pools are closed, restrooms are locked, playground equipment is chained off and trails and bridges are impassable. Due to this growing list of repairs needed, PP&R predicts that without new and stable funding, one in five of its assets are likely to fail within the next 15 years.

This issue of capital maintenance funding for parks is overshadowed by another funding problem— our parks operations rely heavily on repeated five-year operating levies, which results in threatened cuts to park’s popular programming every five years. The choice seems to be between programming or maintenance— and programming has many advocates. Our small group wanted to follow FOSOP’s model to advocate for the sustained stewardship of our parks.

Portland’s park system scores near the top of the Trust for Public Land’s ParkScore rating, and its parks are recognized nationally for their distribution, variety and beauty. But Portland’s Parks Bureau has a sizeable maintenance backlog. In addition, Portlanders recently voted in a new form of government which has changed the way city bureaus are run. How has the new governing model affected how the parks bureau and its funding is handled?

In 2021, Portlanders voted in a new city charter, and we have embarked on a political experiment. In Portland’s old form of government, city bureaus were led by one of four councilors (elected city-wide), at the discretion of the mayor. Unlike any other large city in America, we had no city manager.

As of January 2025, the bureaus are now combined into larger Service Areas that are managed by a new City Manager. In addition, Portland is now divided into four geographic districts with three councilors elected (using a ranked choice method) from each district and charged with setting city policy directives. Remarkably, it was left to these 12 new councilors to decide how to organize themselves into a Council after their election.

Against this background, the financial foreground for city funding appears grim. Portland’s once thriving downtown has not bounced back from the exodus of workers and businesses following Covid’s lockdown; the protests-turned-riots of 2020-21, which saw the damage and removal of many of our parks’ sculptures; and the surge in homeless and mental health sufferers needing critical support. Tax receipts from downtown real estate are plummeting. And with Portland’s high tax rate for citizens second only to that of New York City, the governor has called for a three-year moratorium on new taxes.

However, our Olmsted group was galvanized by these challenges and saw a golden opportunity to stop kicking the can down the road and use this moment to develop a new funding model for our parks— one which addresses the capital maintenance backlog, delivers core services on an equitable basis and provides for the expansion of the system to underserved areas.

Several organizations, including the Olmsted Network, now regularly meet via Zoom to discuss Portland’s parks. What has come out of these meetings, and how do you see them shaping park efforts moving forward?

Our group began hybrid meetings monthly. JCO’s 1903 report did not just sight future parks but also articulated a comprehensive strategy for managing the oversight of urban parks systems. From JCO’s report, we developed our mission statement, but we remain an unstructured coterie of individuals with no board or staff. From the original group of 20, calling ourselves the Olmsted Group, we now number 57 individuals who are members of 25 organizations working in partnership with PP&R and have taken the name the Portland Parks Alliance (PPA).

Our first decision was to meet with candidates for the 12 new council positions in District-focused Park tours. However, when 90 candidates materialized for those 12 Council positions, the tours were put on hold until after the election.

We pivoted. We worked with the Portland Parks Foundation and developed a park-focused questionnaire for the candidates. The Foundation emailed the questionnaire to all the candidates and their answers were thoughtful and illuminating.

After the election, we immediately contacted the elected councilors to set up the park tours. Accompanying the councilors on these tours were park volunteers, friends group and conservancy leaders, local neighborhood associations and advocates. We shared the variety of parks in their district along with some of the maintenance issues and then sat down to hear their thoughts and share our concerns. Through the tours, we have built relationships with our councilors and discovered important advocates.

We have also met with PP&R leadership and have invited them to speak at our monthly meetings. We have testified at City Council meetings and Council committee meetings. We are building relationships with and offering our suggestions and support to our elected leaders and city staff as they deal with a now sizable city budget shortfall, as I discussed earlier.

Dede’s prescient request for a “working session” meant volunteer leaders in park friends groups and park conservancy leadership met together for the first time. Rather than advocating for the maintenance of one’s own individual parks, we are now able to advocate for all our city’s parks. The PPA insists that Portland’s elected leaders are responsible for stewarding the 150-years of investment Portlanders have made in our city parks for future generations to use and enjoy. With one in five park assets threatened to fail by 2035, we share that there can be no programming without our park assets.

Suzanne Bishop is a board member of the Portland Parks Foundation, the Portland Garden Club, IN A LANDSCAPE: Classical Music in the Wild and the Oregon Historical Society. She volunteers in the Washington Park International Rose Test Garden but her ‘home’ park is the South Park Blocks, Portland’s oldest park.