The Olmsted Brothers’ output spanned a remarkable range from preserving scenic wilderness to designing formal civic parks. The firm successfully connected these different kinds of landscapes within increasingly ambitious and complex metropolitan park systems built at the turn of the twentieth century.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. (1870–1957) demonstrated an ability to think across the full spectrum from wilderness to city in his work of 1911-1914 in Denver, Colorado. Today, the outcome of his work is compressed as layers in a single view when one stands on the steps of the Colorado State Capitol. The formal landscape of Civic Center Park occupies the foreground while the wild and seemingly untouched Rocky Mountains rise in the background, beckoning urban dwellers to Denver’s Mountain Parks. The story of how these differing landscapes were conceived reveals themes driving the City Beautiful movement and the emergence of scenic tourism in the United States.

In December 1911, a joint committee of representatives from The Denver Chamber of Commerce, The Denver Real Estate Exchange and the Denver Motor Club invited the Olmsted firm to help make the Rocky Mountains accessible to tourists and the people of Denver by adding a chain of parks far outside of the municipal boundaries and connected by well built roads. The era of automobile had recently dawned, making greater distances suddenly within reach for a rapidly increasing number of people.

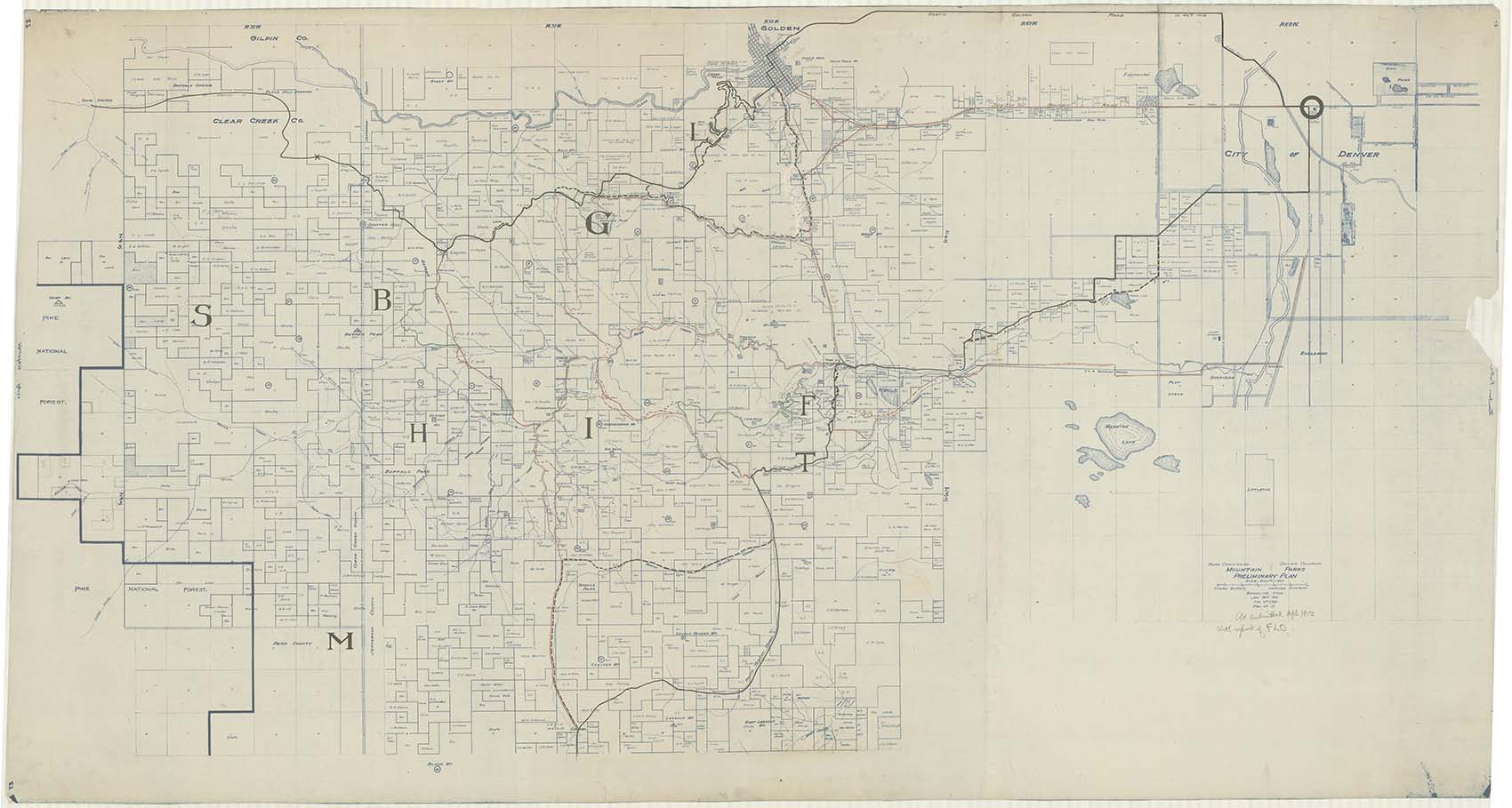

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., then a full partner at Olmsted Brothers, accepted the commission and traveled to Denver to make a thorough reconnaissance over roughly 250 square miles of remote and mountainous landscape on horseback. His direct experience of the landscape, combined with careful analysis of land ownership, resulted in the report to the Denver Parks Commission of April 1913 recommending the acquisition of an astounding 41,320 acres of park land. Included were scenic mountaintops such as Lookout Mountain and Bergen Peak as well as valleys including land along Bear Creek. After Denver voters authorized funding to develop the parks through a dedicated property tax, Denver began acquiring park land in 1914.

The essential character of the natural landscapes was to remain as untouched as possible while locating a roadway from which to exhibit the scenery. Across the United States, the popularity of the automobile demanded improvements in road building of all kinds. Olmsted’s pioneering work on the Denver Mountain Parks was an early expression of ultra-sensitive scenic roadbuilding techniques that would soon after be expanded in the National Parks. In an October 1913 report, Olmsted directs “the smaller the extent of obviously artificial and manhandled surface, whether in the roadway or adjacent to it, the better it is for the mountain scenery.”

The road up Lookout Mountain was the first section of road completed in 1913 and was designed to never exceed a six percent grade to allow for easy and safe travel. A carefully choreographed experience, the road is a study of ever-changing scenery revealing itself through motion. Throughout the system of parks, sources of water were provided at intervals along the route for refreshment of the tourist and to serve the needs of early automobiles prone to overheat. Olmsted included shelters to “protect people caught in a storm” though opined “except in stormy weather, a roofed shelter is a distinctly undesirable thing in the Mountain Parks.” École des Beaux-Arts trained Denver architect Jacques Benedict later designed an exceptional collection of rustic park shelters using materials indigenous to the site so the structures reflect and uplift their surroundings.

Simultaneous with his work in the Mountain Parks, Olmsted, Jr. consulted on the design for Denver’s Civic Center. His work on the National Mall in Washington DC as part of the McMillan Commission prepared him well to advise on the design of Denver’s ambitious plans to clear several blocks of buildings and bring into coherent relationship existing civic buildings including the Colorado State Capitol and the Main Library of 1909. Similar to the National Mall, Denver’s Civic Center Park is structured around a cruciform major and minor axis. Architect Arnold Brunner collaborated with Olmsted to produce a plan richly-punctuated by fountains, sunken gardens, and a music pavilion set in a grove.

Denver began construction of its new Civic Center Park in 1914. Several years later, Edward H. Bennett was commissioned to consult on the design of the park then under construction. Though changes were made to the original design, Bennett built upon the essential structure Olmsted established. Civic Center was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2012.

Thanks in part to the Olmsted Brothers, Denver enjoys a multifaceted park system containing both urban parks and scenic wilderness that connects the city visually and physically to the Rocky Mountains. Olmsted Jr.’s unique vision for the Denver Mountain Parks has been realized as “a place where [people] are not only at liberty to camp, to picnic and wander at will, but where they can […] with a consciousness that the right to do so has been permanently secured to them.” Over a century later, this far-reaching vision has proven invaluable to define the character of a growing city in a magnificent setting.

Tommy Matthews is Associate Principal and Environmental Graphic Designer at Tryba Architects, Denver, Colorado.