When Woodrow Wilson signed the legislation establishing the National Park Service in August 1916, over six years of efforts by park advocates, including J. Horace McFarland, Robert Sterling Yard, Horace M. Albright and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., were finally rewarded.

It was Olmsted Jr. who insisted that the legislation include an explicit statement of the purpose of the parks and he drafted this portion of the bill. “The fundamental purpose …” of the parks, he wrote, “… is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

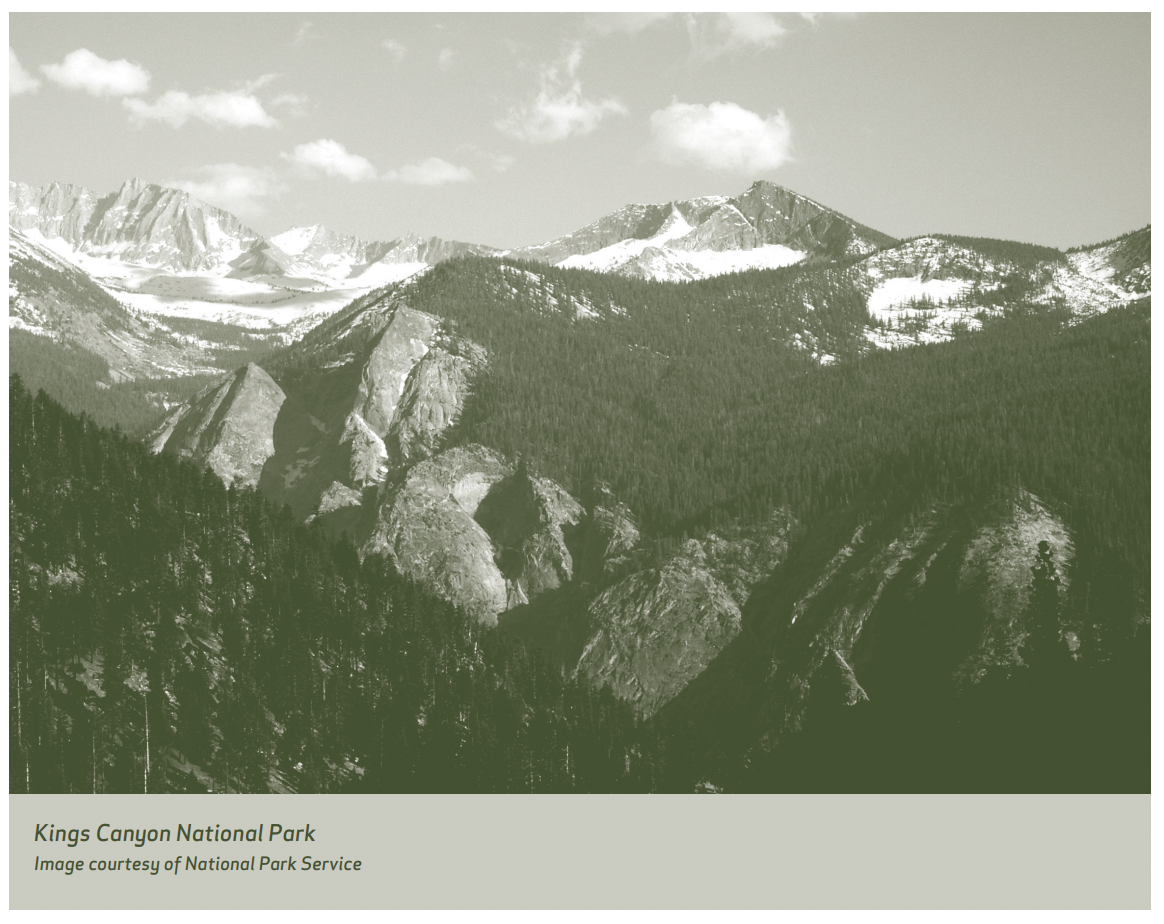

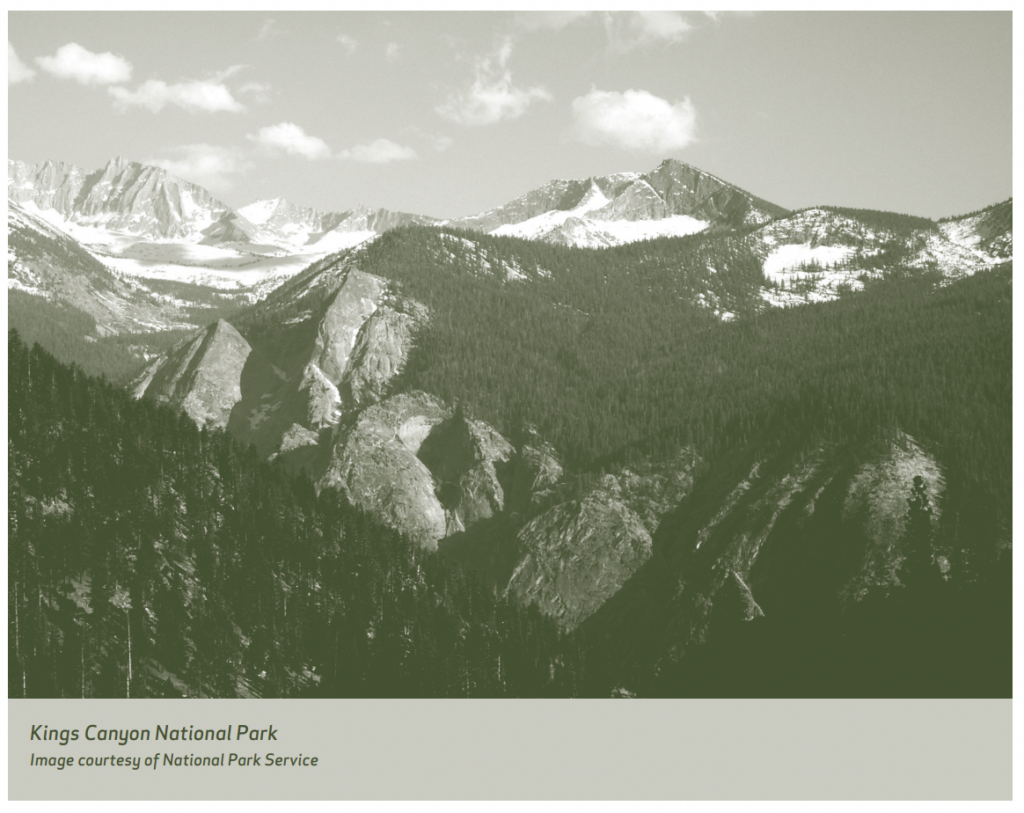

Olmsted Jr. remained intensely interested in the federal agency he helped create. The memorandum reprinted here was part of a 1934 review of U.S. Forest Service plans for the development of the Kings Canyon area in California, which was then still part of the Sequoia National Forest. Forest service officials endorsed Olmsted’s conclusions and had this portion of his report distributed, noting that the specific observations regarding Kings Canyon should apply generally to wilderness areas in national forests.

In 1935, Landscape Architecture magazine reprinted the circular letter as an article. Kings Canyon was a remote wilderness area with dramatic Sierran scenery that had been compared to Yosemite Valley since the 1870s. Although it had been part of a federal forest reserve since 1893, preservation advocates had pressed for the more complete protection of national park status for decades. In 1934 Congress was preparing to consider new legislation to create a Kings Canyon National Park, which would have transferred jurisdiction of the area to the National Park Service.

By accepting and distributing Olmsted’s report, forest service officials were trying to show that they were worthy stewards of the area, implying that park designation might not be necessary. The issue of how and where to protect wilderness on public lands had become a heated issue by the mid 1930s, largely because of the extensive road building and recreational development made possible by the Civilian Conservation Corps and other New Deal programs. Olmsted argues here that officials should not repeat the mistakes made at Yosemite Valley by allowing hotels and other “amusements” that would make the area a destination for reasons other than the appreciation of its unique scenery.

His recommendations were not unlike those made by his father in 1865 for Yosemite Valley. In 1940 Congress finally established Kings Canyon National Park, and in 1946 Olmsted again reviewed development plans for Kings Canyon, this time at the request of the Sierra Club, of which he was vice president at the time. Published in the Sierra Club Bulletin the following year, the report reiterated many of the convictions contained in this article: development of the wilderness park should remain the absolute minimum that would provide for reasonable access and primitive camping. In part due to his efforts, Kings Canyon has remained far closer to that ideal than Yosemite Valley.