Last year, Oregon State University Press published a new book detailing the wonders of Portland’s largest park. “Forest Park: Exploring Portland’s Natural Sanctuary” by Marcy Cottrell Houle includes 21 hikes covering 75 miles through the park, all illustrated with full-color maps and photography. Houle, a biologist, documents each route in detail, pointing out the park’s features.

“Hikes are grouped by theme to encourage people to explore Forest Park’s watersheds, geology, lichens and mosses, vegetation, amphibians and reptiles, pollinators, native wildlife, and wildlife corridors,” the publisher writes. Recently, Houle agreed to answer a few questions we asked about her work.

Q: What drew you to write about Forest Park? What are Forest Park’s distinctive features?

Growing up in the West Hills of Portland, Oregon, Forest Park was the backdrop to the city and, even more, almost in my backyard. I was drawn to these beautiful woods as a child and spent many happy hours with my family walking on its shaded trails. Then, much later, after college and graduate school, I became a wildlife biologist. Remarkably, my first job brought me back to Portland and an exciting opportunity: to research the plants and animals of Forest Park and to develop some management strategies for the Park Bureau to consider. Even more fun, my research was the first ever in-depth study of the park!

While I had always loved the park and considered it a special and beautiful place, it was not until I began studying it more closely that my eyes were opened to what an outstanding park it truly was. It housed hundreds of native plant and animal species. The diversity of its species, some very sensitive, was outstanding. And its size alone– at 5,200 acres– made it the largest forested city park anywhere in the country.

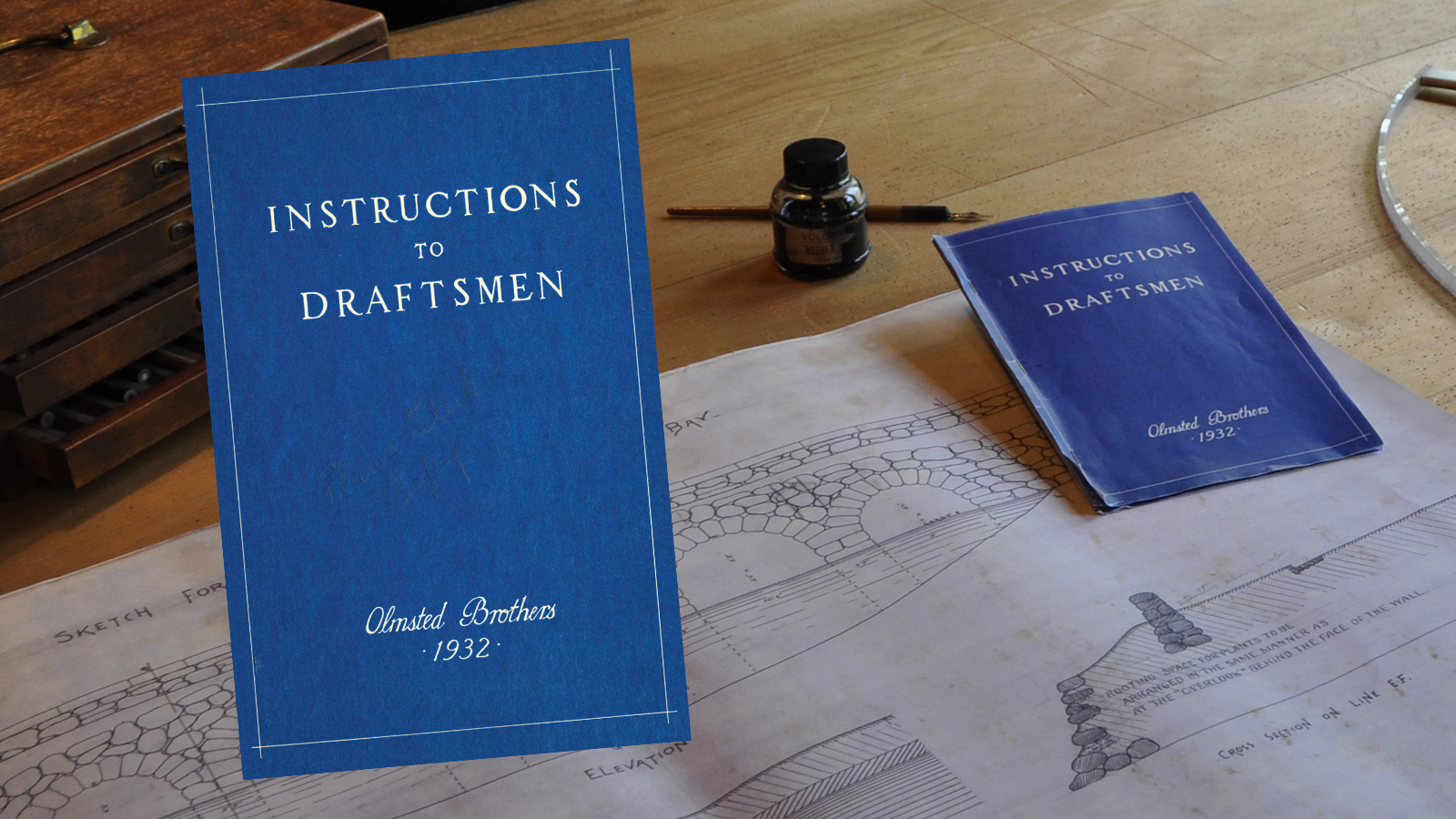

The more I learned, the more important it seemed to write about this place and let others know what a spectacular park existed in our city! Then, discovering its connection with the Olmsted Brothers only made the story more fascinating, and a tale that needed telling since it was astonishing that Forest Park even existed at all!

Q: What is the Olmsted Connection to Forest Park?

In 1903, under the direction of the Portland Park Board, John Charles Olmsted traveled to make a park-planning study for the city. Thoughtful, perceptive, and wise, he made several far-reaching suggestions. One idea was planning a circuit of connecting parks that looped around the city like a natural necklace. Later these would be known as Portland’s famous “40 Mile Loop.” He also proposed another visionary concept: that the hills west of the Willamette River be acquired for an extensive park of wild woodland character.

“Along the hills northwest of Portland,” wrote Olmsted, “there are a succession of ravines and spurs covered with remarkably beautiful primeval woods…. Future generations will bless the men who were wise enough to get such woods preserved. Future generations will be likely to appreciate the wild beauty and the grandeur of the tall fir trees in this forest park… its deep shady ravines and bold view-commanding spurs, far more than do the majority of the citizens of today, many of whom are familiar with similar original woods. But such primeval woods will become as rare about Portland as they now are about Boston. If these woods are preserved, they will surely come to be regarded as marvelously beautiful.”

The Olmsted Report was visionary. Unfortunately, after two failed bond measures to purchase land to implement the Olmsted proposals, it soon was forgotten. The Plan became buried along with other documents and left to gather dust. Making matters worse, in 1912 there was a shift in politics in Portland. The organization of the Park Board– which had been independent of politics, as the Olmsteds had said it should— was changed by City Charter. A new mayor, Joseph Simon, was elected. He had his own idea about parks: they weren’t necessary.

“I am going to stop all extravagance,” Simon wrote. “I do not believe in buying up property for parks all over the city. In my judgement, it is unnecessary to expend such large sums in beautifying this city.”

What did this proclamation mean for the future of Forest Park? Eager land speculators enthusiastically laid out massive subdivisions across miles of forest. At the same time, hills were rapidly being logged. If not for a down turn in the economy and Mother Nature executing terrible rainstorms washing out roads to the imaginary homesites, Forest Park may never have existed.

But these events did happen, and they bought Forest Park time. New citizens became advocates for the park, and sleuthing historians rediscovered the Olmsted Report. Thanks to their activism, the Olmsted Plan was resurrected and fought for. It changed the course of Portland history. Forty-five after the Olmsted Plan was written, in 1948, 4200 acres were dedicated as Portland’s Forest Park.

Since then, other innovative measures have shaped the history of Forest Park. One thousand more acres have been added. In 1995, a management plan was produced for the park, written by numerous scientists and experts. What makes this plan unusual, even unique among all urban parks, is that this plan became law, with the high goals to preserve the wonders of this forest. Titled the Forest Park Natural Resources Management Plan, its vision soundly aligns with Olmsted principles of connecting people with nature and is wonderfully captured in its mission statement:

“Forest Park represents an unparalleled resource where citizens can enjoy the peace, solitude, ruggedness, variety, beauty, unpredictability and unspoiled naturalness of an urban wilderness environment. [t is] a place that maintains this wilderness quality while allowing appropriate passive recreational and educational use without degrading natural resources; an urban laboratory for environmental research and resource enhancement and restoration. [It is] America’s premier urban ancient forest.”

Since that time, exciting new research is being conducted and the splendor of the park continues to be revealed.

Q: You have been advocating for Forest Park to be designated as the first Olmsted-designed Park to be an Urban Biodiversity Reserve. Please explain.

With its outstanding attributes, Forest Park serves as a sanctuary for wildlife, plants, lichens, mosses, amphibians, pollinators, healthy watersheds, and more. It is also a sanctuary for people. The park is a living laboratory for scientific investigation into the protection and stewardship of land, water and biodiversity. Remarkably, it affords many of the qualities that the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve program seeks in terms of its goals. What is surprising, however, is this place exists in a major city!

For these reasons, I believe it is time we go to the next level for this extraordinary place: to designate Forest Park as the nation’s first Urban Biodiversity Reserve. It could act as a model and inspire their creation around the nation. It would raise people’s awareness so that Forest Park’s natural heritage can be protected and transmitted to future generations. And, it would be indeed fitting to have such a designation be given to an Olmsted-designed Park, which makes perfect sense when one considers the moving words of Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.:

“A well-designed park is a gift to future generations, a legacy of beauty and inspiration.”

“Parks… are place of healing and renewal… a sanctuary for the human spirit.”

Marcy Cottrell Houle’s Forest Park: Exploring Portland’s Natural Sanctuary is available from OSU Press.

All photos are by the author and used with her permission.