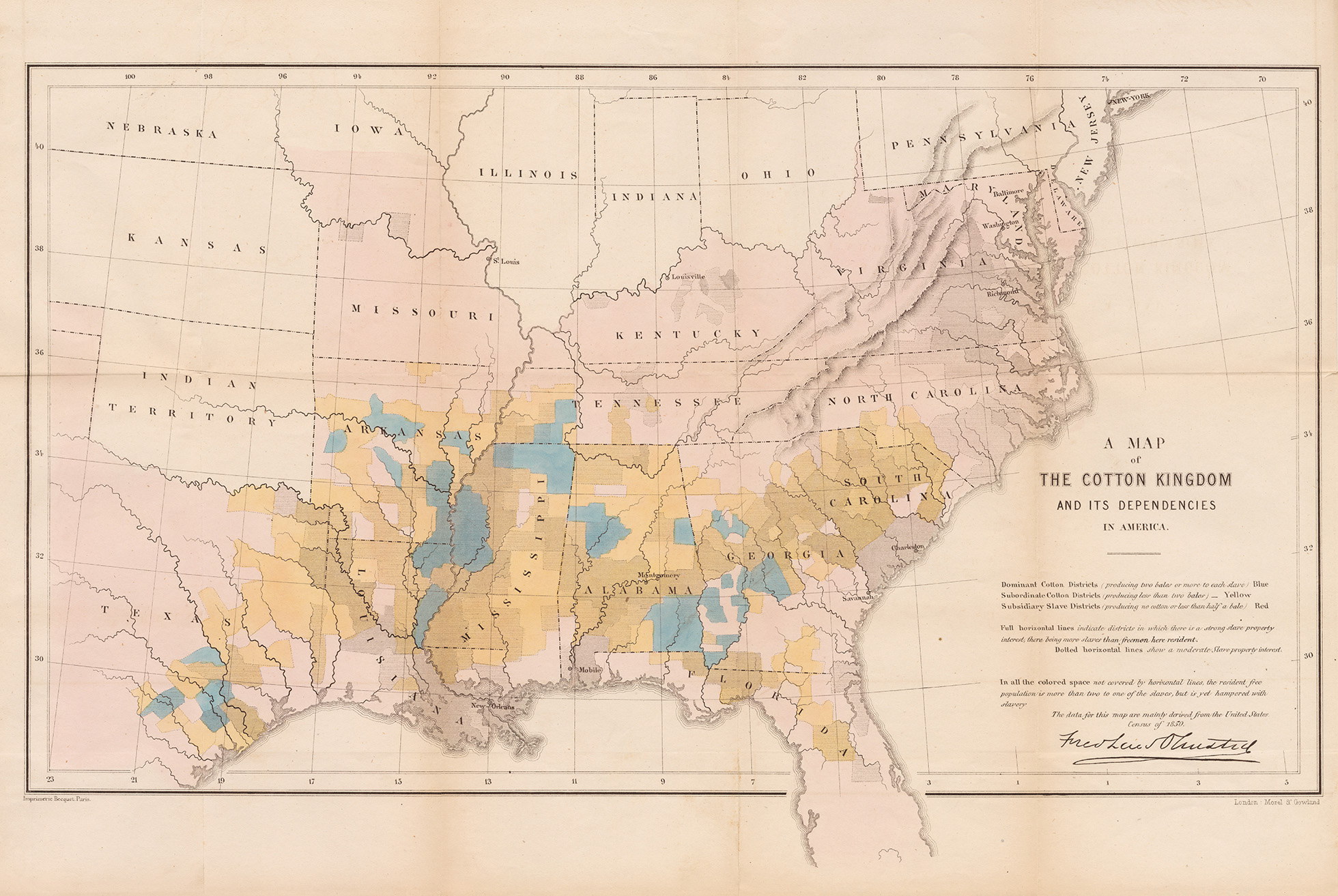

When Frederick Law Olmsted wrote Cotton Kingdom, he articulated “the most staunchly antislavery position he had taken,” says landscape architect Sara Zewde.

“Olmsted certainly describes the condition of enslaved people in jarring terms,” says Zewde, who also teaches at Harvard University, “but does so to characterize their condition as a function of their enslavement and not a biological condition.”

Wherever he was, and whatever he was doing, Olmsted focused on ways to elevate civil discourse and contribute to the betterment of society. He was a creative thinker and prolific writer.

Olmsted’s trip to England in the 1850s led to the publication of his first book, Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England. That, in turn, led to employment as correspondent for the New York Daily Times, where he crafted posts under the pseudonym Yeoman and opposed slavery in the south. Later that decade, Olmsted became a partner in a publishing house and managing editor of Putnam’s Magazine, a magazine of literary and political commentary. For six months, as editor, he resided in London, becoming acquainted with the English literary establishment and further exploring the public parks and landscapes around the city.

In these roles, he became part of the literary establishment at home in America — Emerson, Longfellow, Melville, Irving — whose company he enjoyed and whose thoughts inspired his own thinking and writing. In perhaps the best letter of recommendation of all time, Washington Irving and other well-known writers endorsed Olmsted for the superintendent’s job at Central Park, a job for which he had no apparent qualifications.

A Prolific Writer and Thinker

In the following decade, Olmsted and E.L. Godkin conceived of a new weekly publication, which by 1865 evolved into The Nation. Olmsted remained a co-editor until 1868 and the magazine’s articles and opinions were substantially shared or shaped by him, including its advocacy of the Freedman’s Bureau, support for women’s suffrage, and the zeal to make the Capitol City, Washington, D.C., a source of national pride.

Olmsted was a “founding figure in the formation of American landscape architecture,” says Zewde, who “worked actively on societal issues. The explicit interface of beauty, design and political engagement is central to our discipline.”

I want to make myself useful to the world… to help advance the condition of Society… as well as other things too numerous to mention.”

Frederick Law Olmsted

By the end of his life, Olmsted had written five books, crafted thousands of articles and letters, and produced and often paid for the publication and distribution of numerous reports. Six-thousand letters and reports written by Olmsted have survived, dealing with 300 design commissions. The full list of his publications, including letters describing his southern journeys and various documents published by the U.S. Sanitary Commission, contains more than 300 items.

Today, the Olmsted Archives at Fairsted contain over 1,000,000 original documents related to the more than 6,000 landscape design projects undertaken by Olmsted and the Olmsted firms. The Library of Congress houses thousands of pages of correspondence from the firms, as well. The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, edited by Series Editor Charles Beveridge (whose scholarship informs this website), populate 12 volumes and can be accessed via the HathiTrust and libraries. The Plans and correspondence can be accessed here.