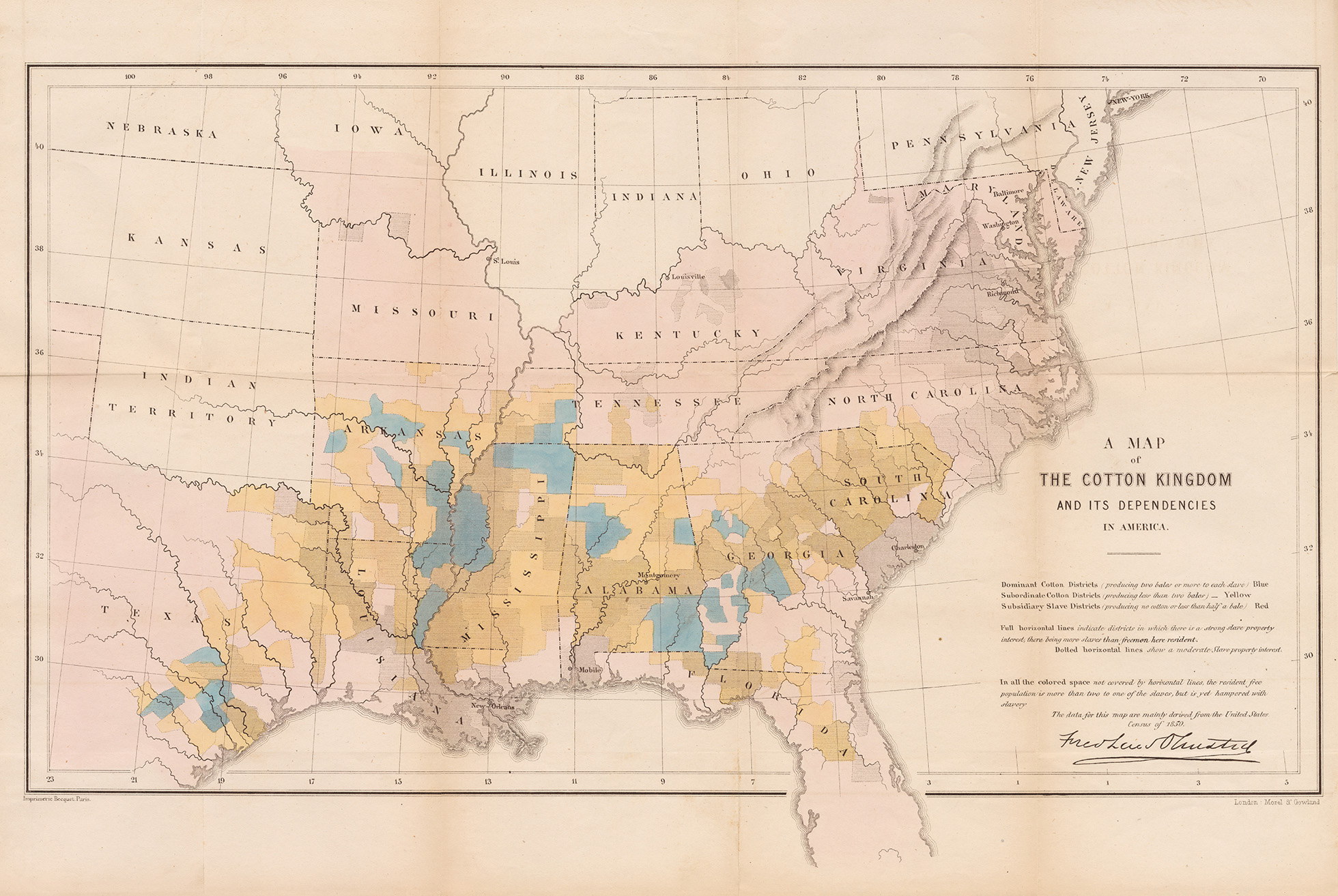

Before becoming arguably the most famous landscape architect in the United States, Frederick Law Olmsted, as a reporter for the New York Daily Times, spent years drawing attention to the horrors of slavery in the American South. Reflecting on his travels throughout the “Cotton Kingdom” on the eve of the Civil War, Olmsted rendered a stark verdict on the system of human bondage that so many in the South were willing to fight – and die – for. “It is said that the South can never be subjugated,” Olmsted wrote in 1861. “It must be, or we must. It must be, or not only our American republic is a failure, but our English justice and our English laws and our English freedom are failures.”[i]

For Olmsted, there was a distinct physical manifestation of slavery in the American South. Throughout the region, Olmsted witnessed the privileging of private land over public space; plantations, whose very existence was made possible by the free labor of Black bodies, seemed to be the only sites worthy of substantial investment. Public spaces like parks, libraries, and town squares for those outside of the elite plantation class were rare and, if they did exist, had often fallen into disrepair. The privatization of space in the antebellum South therefore did more than create physical monuments to the inequalities of slavery; it also shaped an environment that had little to provide non-slaveholding Southerners. Such a reality touched upon social, aesthetic, and practical concerns. There was very little mixing between southern elites and anyone else, as spaces of beauty were reserved solely for the upper class. At the same time, there were few spaces that addressed the public health of the majority of the region’s inhabitants. Not surprisingly, Olmsted took note of the sickly, unhealthy nature of many he came across during his travels.

Among those who study the work of Olmsted, there is a growing consensus that Olmsted’s experiences in the South had a profound impact on his later career as a landscape architect who would design some of the nation’s most beloved parks. Writing on Olmsted’s legacy within the field of landscape architecture, Harvard University professor Sara Zewde has found that “It was very clear to me how the discipline’s actual founding was propelled by the South.” In a myriad of projects completed following the end of the Civil War across the United States, Olmsted sought to proactively address the deficiencies that he had seen in the undemocratic landscapes of the American South. It is within this conversation between historical moments and geographical regions that we can begin to see the continued importance of Olmsted to a variety of American cities in the twenty-first century city. As Zewde notes:

“When you’re born in a Black body in the South, you are prompted to an awareness about the histories of landscape that may not be taught or memorialized. Yet and still, the very visceral experience of going to these spaces and being able to so clearly track the past through Olmsted’s words and the present with my own eyes offered new levels of understanding to me about these places, and in fact, this history.”[ii]

Does this mean that the Olmsted of the nineteenth century comes to us ready to address all the issues of the present moment? Of course not. While Olmsted was anti-slavery, he was not necessarily a public abolitionist (though he was a much more strident critic of the institution in his private correspondence). And the development of New York’s Central Park led to the demolition of Seneca Village, a predominantly African-American community. Those interested in a complete history of Olmsted and his work must not shy away from such realities.[iii]

Yet one must also contend with the role of ideas in any assessment of Olmsted’s legacies – and the ways those ideas were informed by Olmsted’s evolving understandings of such concepts as access, equity, and democracy. As Zewde and others have noted, the theory behind Olmsted’s practice was undoubtedly shaped by what he witnessed throughout the American South. Yet Olmsted’s practice suggests a true commitment to the theory, for example, of equitable access to public space for all Americans. For Olmsted, real public spaces served as reminders of America’s democratic promise: everyone (physically) had a space here. Importantly, Olmsted also saw such public spaces as sites where social integration could occur. For a country often riven by segregation of all sorts, this potential was of great importance to Olmsted. Writing on his work in New York’s Prospect Park, Olmsted found that “You may thus often see vast numbers of persons brought closely together, poor and rich, young and old, Jew and Gentile.” One cannot have a functioning body politic without a functioning body. It was in such spaces where Americans could find joy in coming together.[iv]

It must be noted that the demographics of the cities where Olmsted did much of his work have changed considerably over the years. Yet many of his parks remained popular as such shifts occurred – even when those enjoying such spaces had no idea of the history behind them (this, too, was by design. Writing in 1882, Olmsted noted that he strove to keep his approach “simple and natural,” employing design strategies for parks that “touch us so quietly that we are hardly conscious of them.”). Yet as the work of Zewde and others suggests, there is great value for our contemporary moment in putting these histories in conversation with present realities. As the market-driven policies of neoliberalism continue to call into question the existence of such spaces as parks, Olmsted’s vision of a public and democratically accessible infrastructure of social goods reminds us of a usable past that could counter the belief that the privatization of such spaces is the only way to go. As more and more spaces seem to be designed exclusively for the wealthy, Olmsted’s commitment to the promise of such a strategy – and to the benefits of designing truly inclusive spaces – provides a road map for strengthening public spaces for the twenty-first century.[v]

Finally, Olmsted’s articulation of the horrors of slavery and benefits of integration may provide new ways to envision the relationship between race and public space in the new millennium. Such a possibility does not mean casting Olmsted as any sort of anti-racist pioneer; he was a flawed white man who shared many of the prejudices of his era. Yet in putting Olmsted in conversation with new actors – actors that often come from the communities of color that are now located near Olmsted’s parks – we may come to see both a reinvention and rebirth of his ideas, recast for a new environment and a new set of challenges.

[i] Frederick Law Olmsted, The Cotton Kingdom: A Traveller’s Observations on Cotton and Slavery in the American Slave States, Vol. I (London: Mason Brothers, 1861), 2.

[ii] Zewde quoted in Alice Bucknell, “In Cotton Kingdom, Now, Sara Zewde retraces Frederick Law Olmsted’s route through the Southern states,” News: Harvard University Graduate School of Design, January 13, 2021: https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/2021/01/in-cotton-kingdom-now-sarah-zewde-retraces-frederick-law-olmsteds-route-through-the-southern-states/.

[iii] Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992).

[iv] Frederick Law Olmsted, Public Parks: Being Two Papers Read Before the American Social Science Association in 1870 and 1880, Entitled, Respectively, Public Parks and the Enlargement of Towns and a Consideration of the Justifying Value of a Public Park(Brookline, MA, 1902), 40.

[v] Frederick Law Olmsted, “Trees in Streets and in Parks” (September 1882), in The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, volume VIII: The Early Boston Years, 1882-1890 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 594.

Michael H. Carriere is a professor of history at the Milwaukee School of Engineering. He is the co-author, with David Schalliol, of The City Creative: The Rise of Placemaking in Contemporary America (University of Chicago Press, 2021).