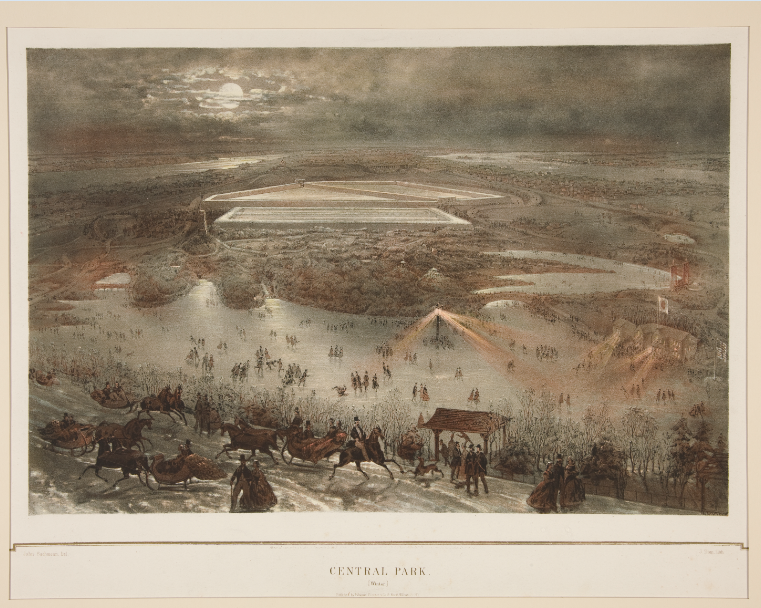

Central Park is made up of a variety of landscapes that are diverse, intricate, and interconnected—just like the communities of Park-lovers who enjoy them. Each year, 42 million visitors come to the Park to find sanctuary, socialize, and connect to their passions: birders, bikers, wildlife enthusiasts, runners, walkers, caregivers, dog owners, and more. Different types of terrain not only allow all of these groups to use the Park for a wide range of purposes; they also work in harmony with one another to comprise the wider Park ecosystem and fulfill its original purpose.

Landscape variety was key to Frederick Law Olmsted’s vision for Central Park over 160 years ago. “[The beauty of the Park] should be the beauty of the fields, the meadow, the prairie, of the green pastures, and the still waters. What we want to gain is tranquility and rest to the mind,” Olmsted stated in 1870. If the Park was going to elicit the same “sense of enlarged freedom” that comes from being in nature—but in the heart of a growing city—its landscapes had to reflect the variable topography of nature itself.

Olmsted and co-designer Calvert Vaux came up with this plan for Central Park and its many unique landscapes during a design competition run by Park commissioners from 1857 to 1858. Their winning plan, called the Greensward plan, beat our 32 other submissions and featured landscapes that felt untouched and natural—despite the effort and construction this would take to fabricate and maintain. While this style of park is commonplace today, at the time, the idea of an urban park that mirrored natural landscapes was fairly progressive. The standard for major urban parks of the era was largely dictated by Europeans, whose greenspaces tended to be formal, ornamental, and heavily manicured. While some of Vaux and Olmsted’s competition leaned into a similar natural aesthetic, many other designers submitted plans that consisted of palaces, fountains, terraces, concert halls, museums, manicured gardens, terraces, and carriage concourses.

Though Central Park has changed significantly throughout history, it still embodies the Greensward plan’s original intent to provide New Yorkers with a serene space that is reflective of natural topography. Today, each landscape—from lawns to water bodies to woodlands—serves a vital role in keeping the various plants, animals, and people who rely on the Park healthy and happy. Read on to learn about Central Park’s different landscapes and how they fit into the Park’s ecosystem:

LAWNS

If you’ve ever visited the Park on a warm, sunny day, one thing is clear: Lawns are some of our most adored landscapes. With their soft, comfortable, and beautiful green surfaces, they provide an optimal space for sunbathing, picnicking, casual lawn games, and making memories in the Park. Beyond being a backdrop for bocce ball and cloud-watching, turfgrass also serves essential functions for the Park and is a vital component to the health of this urban greenspace. Healthy lawns can reduce noise, mitigate flooding by slowing water’s horizontal movement, decrease urban heat, and prevent erosion.

While you can find turfgrass to lounge or play on in many places throughout the Park, some of our favorite sprawling lawn landscapes include the Great Lawn, East Meadow, and Sheep Meadow.

WOODLANDS

The term woodland is often used broadly to describe a landscape covered in trees, but there are many types of woodlands with varying degrees of tree density. Much like the landscapes of the Catskills or the Adirondacks that inspired Central Park’s woodlands, these Park ecosystems have an open tree canopy that facilitates a diverse variety of animal and plant life. The canopy provides coverage and habitat for various wildlife, while still allowing enough sunlight for plant photosynthesis below, resulting in a landscape that is rich with biodiversity. The expansive 40-acre North Woods is the largest of the Park’s three woodland landscapes, followed by the popular 36-acre Ramble and the intimate four-acre Hallett Nature Sanctuary. The Park’s designers celebrated woodland landscapes for their ability to give New Yorkers a sanctuary and an immersive experience of nature that may otherwise be inaccessible to many city-dwellers.

WATER BODIES

There are nine bodies of water in Central Park: the Pond, the Gill, Turtle Pond, the Loch, Conservatory Water, the Pool, the Reservoir, the Lake, and Harlem Meer. Although many of these water bodies look natural, they are all human-made to mirror those found in nature. The watercourse on the Park’s north end was originally designed to allow water to flow from the Pool to the Loch and into the Meer. The Park’s designers even added large rocks and boulders throughout the Loch to create cascades, or small waterfalls, along the watercourse. The Park’s designers even added large rocks and boulders throughout the Loch to create cascades, or small waterfalls, along the watercourse.

Our current restoration of the Harlem Meer is reconnecting the Loch to the Meer, allowing water from the Pool to flow unobstructed through the water bodies once again. On top of offering serene environments and recreational opportunities, these landscapes also contribute to the Park’s overall biodiversity and create habitats for wildlife like fish, turtles, and waterfowl.

HILLS AND BEDROCKS

Not only are Central Park’s rocks and hills fun to climb on and sled down, they can also tell you a lot about the land’s history. The word “Manhattan” is derived from the Lenape word for this island, “Manahatta,” meaning “island of many hills.” While much of Manhattan’s original landscape has been obscured by development over time, you can see the land’s geological past in the prominent rocks and hills of Central Park. The Park’s rocks were formed through volcanic activity around 500 million years ago and were shaped by more recent glacial activity around 14,000 years ago.

Millions of years after their formation, Central Park’s rocks are prized as some of the Park’s most dramatic and defining features. Summit Rock is the highest natural elevation in Central Park and was a prominent feature in Seneca Village. Vista Rock—the Park’s second-highest point—is home to Belvedere Castle and has served as a site for the National Weather Service to record temperature and wind speeds since 1919.

GARDENS

While stunning flora and blooms can be found around every corner in Central Park, it also hosts a few designated gardens. Among them is the Conservatory Garden: Central Park’s formal garden, a horticultural masterpiece, and one of the most significant public gardens in New York City. The smaller and charming four-acre Shakespeare Garden boasts an array of trees, shrubs, flowers, and herbs mentioned in William Shakespeare’s plays and poems. The North Meadow Butterfly Gardens are particularly important, as they provide habitat for the more than 50 species of butterflies that pass through Central Park.

MEADOWS

The term “meadow” typically refers to an open landscape or habitat that is populated with a more diverse variety of flora than grass alone, like lawns, but isn’t as dense with tree growth as woodlands. Completed in 2017, the Dene Slope is a vibrant and dynamic native meadow that boasts a variety of native blooms and grasses. Though cultivating a native meadow like Dene Slope can be laborious, they are relatively low maintenance once created since native plants have already adapted to the environment. Tall meadow grasses prevent self-seeding invasive species from taking over, and they don’t require mowing.

Amileah Sutliff is the Senior Marketing Writer & Editor at the Central Park Conservancy.