In 1609, when Henry Hudson sailed up the Muhheakantuck, the River That Flows Both Ways, as the Munsee Lenape called it, Manahatta, the Island of Many Hills, was covered in several types of forest and dotted with shallow freshwater marshes. Today, the only forest similar to what Hudson saw from his ship, the Half Moon, is in Fort Tryon Park, at the north end of Manhattan facing the river that now bears his name. Thanks, however, to the foresight of some mid-nineteenth-century civic leaders and the creative genius of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the island has other extensive natural areas such as Central and Riverside parks that give New Yorkers and visitors a break from the urban grid and built cityscape. Central Park, the first joint venture of Olmsted and Vaux, continues to reflect their original vision, meeting the ever-evolving recreational needs of a great metropolis for open space, green landscapes, and places for celebration and contemplation. The park, from its first years, has also inspired many artists to depict its scenery and the ways people enjoy it, giving us, as a few early examples show, another way to appreciate the park’s design and social impact.

The grid that defines Manhattan was laid out, on paper at least, in 1807, long before streets and avenues were paved or lots filled with buildings. But only a few decades later, the inevitability of growth northward was recognized, and plans were made to create extensive green spaces while land was still available. William Cullen Bryant, the poet and editor of the New-York Evening Post, had been promoting the idea for years, and was joined by Andrew Jackson Downing, an influential landscape designer, who between 1848 and 1851 wrote a series of letters in The Horticulturist bemoaning the lack of parks in American cities. The New York City and State governments had considered an area of 153 acres between 66th and 75th streets but concluded it was too small and poorly located. They chose the more central location, which gave that word to the park’s name, when the Croton Aqueduct Board said it needed some of this better-situated area for an additional reservoir to meet the anticipated growth of the city. The park was allocated the land surrounding the reservoir site, from Fifth to Eighth avenues, from 59th to 106th streets; a few years later, the land up to 110th Street was added.

When the legislative and budgetary processes to secure the land were completed in 1853, the designated area had long lost its forests and wetlands. It was mostly a scrubland with a few small settlements, most notably Seneca Village, a primarily African American community between 82nd and 89th streets and Seventh and Eighth avenues. In 1857, the commission established to create the park announced a design competition with very specific guidelines for the features and facilities that the park had to include. Thirty-three entries were submitted – the very last to arrive coming from Olmsted and Vaux, on April 1, 1858. Theirs was perhaps the most detailed and highly illustrated, with nine presentation boards showing parts of the land as it then was and how they proposed to modify it. For added measure, they included a painting by the young landscape artist Jervis McEntee (1828-1891), whose sister Mary had married Vaux in 1854. McEntee’s 1858 painting, View in Central Park, is one of the best images we have of what the land was like at the time. It looks north, showing the depression that Olmsted and Vaux proposed to fill with water to create a lake.

Olmsted and Vaux won the competition. “The primary object in the design,” they stated in their Greensward Plan, “[is] to get the better of the most conspicuous defect of the site, and to take the utmost advantage of such opportunities…..to make the visitor feel as if a considerable extent of country were open to him.” McEntee’s painting surely helped make the point of how much labor would be needed to achieve this. In 1859, as many as 3,800 workers were employed building and planting the park. The park opened in sections, with most of the landscaping in place by 1861. At the site McEntee depicted, Olmsted and Vaux enlarged a natural creek running west to east from 77th to 72nd streets to fill 22 acres of what has ever since been called the Lake. And the Lake has ever since been one of the park’s most significant features, the link between two components of the vision Olmsted and Vaux had for the variety of experiences the park could provide visitors. To the south, the Mall, a broad, straight paved area lined with elms and ideal for promenades meets the lake at the Terrace. Vaux wrote of this site, “The landscape is everything, the architecture nothing—til you get to the Terrace. Here I would let the New Yorker feel that the richest man in New York cannot spend as freely….just for his lounge.” On the north side of the Lake, the formality melts away in the wooded hills of the Ramble. There, as Olmsted wrote to the park’s chief landscape gardener in 1863, his goal was “a sense of the superabundant creative power, infinite resource and liberality of Nature.”

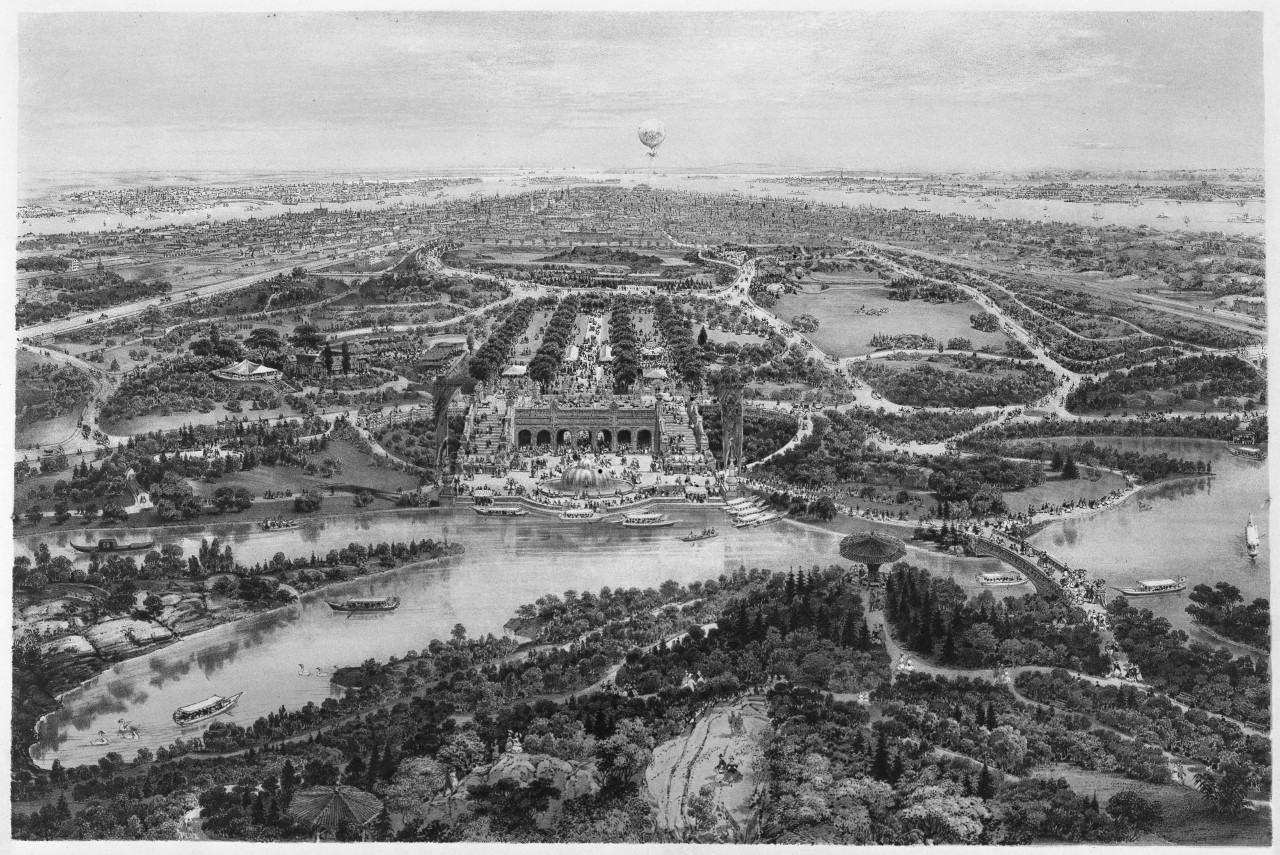

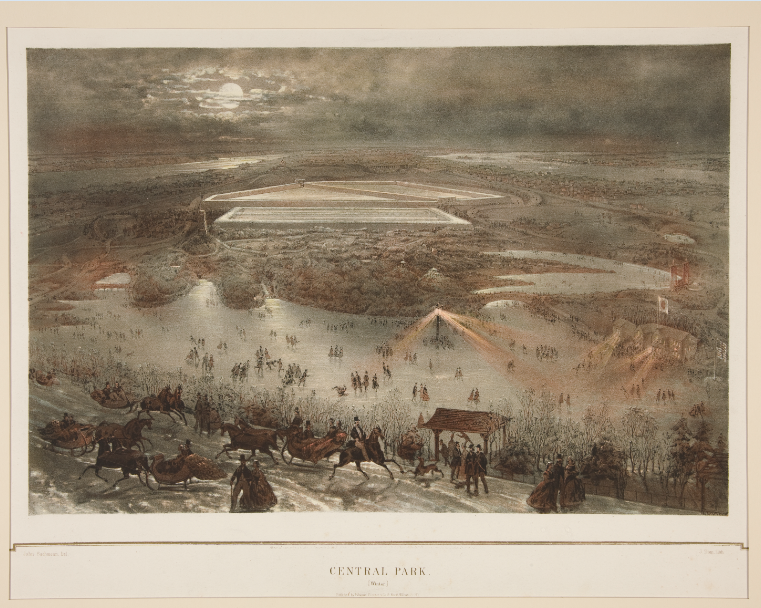

The 1865 aerial view of the Lake, Central Park (Summer), a color lithograph by Julius Bien after John Bachmann, shows how rapidly both goals were achieved. Here, as though in a hot-air balloon like the one in the distance, we hover over the Ramble, looking south to the Lake and the Terrace and Mall beyond, with the Sheep Meadow to the west and the Pond farther south. The avenues bordering the park are as yet hardly built upon, and this print is also valuable for depicting the Terrace before the statue of the Angel of the Waters was installed in 1873. The variety of watercraft and the streams of people in both the formal and natural areas of the park show how popular it was and what a recreational need it fulfilled. On the drives, people ride horses and in carriages. The companion lithograph, Central Park (Winter), looking north over the same scene and to the original and the then-new reservoirs, shows a moonlit night, with riders and carriages on the West Drive and skaters on the frozen Lake.

The pair of images hint at the social changes Central Park made possible in the city. Before, the city offered few outdoor recreational opportunities of any kind. With the park, there were broad esplanades for strolling in a sophisticated landscape evocative of Paris and London. Riding and driving created new jobs and advanced industries in fashion, saddlery, and carriage building; conspicuous consumption, perhaps, for those who could afford it, and entertainment for those who could watch the parade from the walking paths designed to parallel the drives. Skating, previously unavailable in the city, attracted thousands from the very first winter of 1860 when the lake froze; the park was kept open until midnight for their enjoyment. In 1865, skates could be purchased for 25 cents or rented in the park, making them available to almost all classes. The benefits of these recreations were especially significant to women: riding and driving gave them more ways to get out of the house and to exercise, while skating, another newly available activity, not only raised the level of skirts well above the ankle but also gave women on the ice the socially correct opportunity to be arm in arm with a man– a husband, beau, or perhaps even someone not approved but now beyond view of any chaperone!

Roger F. Pasquier has been a regular visitor to Central Park since he was a baby in a perambulator. He is an art historian and ornithologist and author of several books, including Painting Central Park (Vendome Press 2015), which discusses and illustrates the rich history of artists depicting the park. His presentation on paintings of the park can be found on the Olmsted 200 YouTube here.

You can purchase a copy of Painting Central Park here.

Sources:

Creating Central Park by Morrison H. Heckscher (Metropolitan Museum and Yale University Press 2008)

Central Park, An American Masterpiece by Sara Cedar Miller (Harry N. Abrams, Inc. in association with the Central Park Conservancy 2003)

Painting Central Park by Roger F. Pasquier (Vendome Press 2015)

The Park and the People: A History of Central Park by Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar (Cornell University Press 1992)