While Frederick Law Olmsted was in Chicago overseeing landscape design for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition, the nascent City of Milwaukee Parks Commission engaged him to help develop parks for their city. Olmsted agreed to correspond with the commission about potential park sites and then to design three of his choosing.

Olmsted initially visited Milwaukee in February 1892, followed by three more trips until 1894. His team included his stepson, John Charles Olmsted, and Warren Manning, who served as superintendent of planting. (Manning continued to oversee the development of the Olmsted parks in Milwaukee and to consult on additional park planning and design there.)

Olmsted and his firm designed Lake, River (now Riverside) and West (now Washington) parks. He also envisioned Newberry Boulevard as a mile-long linear parkway linking the first two. For West Park, several tracts of land were acquired in 1891, comprising about 125 acres. Located just outside the city’s limits, the park soon was incorporated into the growing metropolis. Olmsted presciently anticipated that the park would help attract new development to that West Side area. It was renamed Washington Park in 1900 and became a vibrant destination. Olmsted successfully urged officials to create a streetcar station near the park, to make it accessible for everyone.

A Scenic Park with Panoramic Vistas

Olmsted appreciated the site’s 15-acre native forest and high rolling hills, with elevations between 130 and 180 feet above Lake Michigan. Though miles away, the lake was visible from some park locations–before mature trees obscured those views. West Park’s “pastoral” design included open, low meadows, the strategic planting of thousands of trees and shrubs, and an ample picnic area. Its central feature was a naturalistic lagoon that also served ice skating and boating. By the early 1900s, the park became Milwaukee’s most popular location for ice skating, according to the park commission’s annual reports.

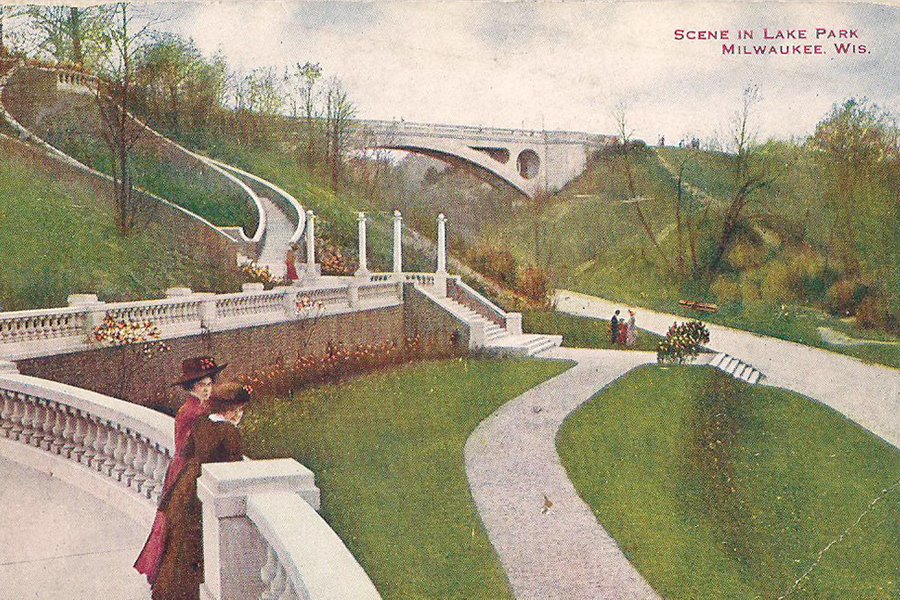

West Park was laid out with separate curving pedestrian walkways and carriage paths. Picturesque vistas highlighted the park’s undulating terrain and lagoon—and were featured on many postcards.

Olmsted’s design also included a one-acre “deer paddock” to accommodate donations of animals by two park commissioners, Louis Auer and Gustave Pabst. This modest beginning soon led to the creation of Milwaukee’s first zoo, which gradually expanded to include over 800 animals on 23 acres. Eventually the zoo outgrew the park and, after years of planning, in the early 1960s it was moved several miles away to its current larger location. After zoo structures were razed, the site was essentially restored to its former pastoral layout and a senior center was built in that area.

Other early additions to the park included a boathouse, a mile-long horse-racing track, grandstands, stables and a wooden gazebo for musical events. Later, basketball and tennis courts, aquatic facilities, playgrounds, and other amenities were added.

In 1938, a much-needed open-air bandshell—the “Emil Blatz Temple of Music”–was built within a natural amphitheater. This Art Deco stage, designed by Fitzhugh Scott, became the site of classical, operatic, pop, and jazz “Music Under the Stars,” concerts, which were attended by thousands and continued until 1992. In recent years the all-volunteer Washington Park Neighbors have been organizing popular community concerts called “Washington Park Wednesdays.”

Disconnection and Decline

“Urban renewal” policies, including the decision to build freeways in the 1950s and ‘60s, shredded the fabric of many city neighborhoods—including in Milwaukee. The block-wide western edge of Washington Park was eliminated to create a freeway spur in 1962, that was intended to connect to another freeway that was never built. Now named Highway 175, that freeway spur separated some neighborhoods from the park, created noise pollution, and decreased safe and welcoming access into it. Shifts in demographics and slashing of park budgets contributed to major disinvestment in Washington Park.

Despite some improvements to Washington Park, including the restoration of the bandshell and regrading of soccer fields, other key elements have remained neglected for decades. Notably, Washington Park’s once-attractive lagoon has become unhealthy and overtaken by masses of invasive cattails. Views of the lagoon are also largely obscured by overgrown vegetation along its edges, making this asset invisible in many areas.

One promising development is that Milwaukee County Parks has announced plans to renovate two deteriorating bridges spanning the lagoon. This project could draw more attention to the lagoon’s needs and potential; restoring it will improve the park as an ecosystem and visitors’ experience of it. A taxpayer-funded Master Plan for the Revitalization of Washington Park can serve as foundation for further planning and decision-making that considers the park as a “unified composition.” After all, that was Olmsted’s emblematic approach to designing landscapes.

Completed in 2000 by Quorum Architects, Inc, for Milwaukee County Parks, the Master Plan’s task force engaged wide-ranging professionals and community members. It offers recommendations about how to respect the park’s distinctive heritage, beauty, and versatility while addressing contemporary issues. For example, the study urged the enhancement of “perceived safety” by keeping the park “as visibly open as possible.” Adherence to the “middle plane theory” is often employed within urban parks. “The theory maintains that people feel more comfortable when there is clear visibility from the ground plane up to the area above eye level where the lowest branches of most deciduous trees begin” the Plan explained. That approach has proven to be compatible with Olmsted’s design concepts in other parks.

Opportunities for Holistic Planning and Connectivity

Circulation was also addressed in the Master Plan: “Another issue that greatly affects how the park is used is the current network of both vehicular and pedestrian paths…We can see how the construction of the highway…spur interrupted major portions of the original plan and caused some traffic and circulation problems within the park.” Some walkways suddenly end, including around the park’s perimeter, or they lead to blind corners and intimidating “walls” of tall vegetation. Neighbors have recently expressed concerns about not being able to safely enter the park–due to convoluted street layouts and the lack of adequate crosswalks and sidewalks. Many paths have deteriorated.

Wisconsin’s Department of Transportation has allocated funding to study the potential of rebuilding Highway 175 into a standard roadway, thus creating opportunities to reconnect the park to all of its surrounding neighborhoods. This DOT study can serve as an impetus to analyze and improve all roadways within and around the park.

In 2022, the Milwaukee County Board of Supervisors passed a resolution to rename the roadway traversing Washington Park as Olmsted Way. “Frederick Law Olmsted’s design of Washington Park deserves to be celebrated. The landscape architecture in the park has shaped how people have enjoyed the space for more than 130 years and will continue to shape how we enjoy it for the next 100,” said Chairwoman Marcelia Nicholson, who introduced the original renaming resolution.

“Having Olmsted Way run through Washington Park gives us the unique opportunity to uplift a historic figure whose work was vital to the development of our parks system,” said Supervisor Peter Burgelis, whose district includes Washington Park.

Some safety issues involving this roadway remain a concern. The Master Plan noted that traffic along this drive “currently travels at speeds exceeding 45-50 miles per hour, with two lanes of traffic going in either direction.” It proposed several traffic-calming solutions, including reducing traffic from four lanes to two. Discussions are reportedly beginning to address those issues.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation, based in Washington D.C., included Washington Park in its 2022 Landslide program of threatened and at-risk cultural landscapes designed by Olmsted. Their report suggested that “All current and future revitalization efforts for Washington Park would benefit from clear, shared overarching principles and guidelines to ensure that development balances both natural and cultural values for a significant work of landscape architecture that is likely eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.”

Greater awareness of Washington Park’s significance as an Olmsted-designed landscape—and historic designations–could help to affirm its value, encourage thoughtful stewardship, and enhance access to grants for its appropriate care. With some 200 other Olmsted landscapes listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including Milwaukee’s Lake Park, many models exist for how to successfully preserve and update Olmsted-legacy parks. Local historic designation of Washington Park, which was favorably reviewed by the City of Milwaukee’s Historic Preservation Commission, was placed on hold and is pending the development of stewardship guidelines. That process had stalled during the pandemic. Olmsted 200 activities have helped to shine light on both the history and potential of Washington Park.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation’s Landslide 2022 report on Washington Park: https://www.tclf.org/sites/default/files/microsites/landslide2022/locations/washingtonpark.html

“The Lasting Legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted,” by Archer Parquette, Milwaukee Magazine, April 2022, https://www.milwaukeemag.com/the-lasting-legacy-of-frederick-law-olmsted-and-his-3-signature-milwaukee-parks/

“Faded Glory: Washington Park still has striking beauty, but years have taken their toll” by Whitney Gould, September 8, 2003, https://www.gregpostles.com/lakepark/gouldarticle/gould/168121.html

Gould interviewed neighbors of an Olmsted park in Newark, New Jersey, who have embraced Olmsted, his design for their park, his democratic ideals and his influence on Malcolm X.

“Olmsted Deserves Recognition in Milwaukee,” by Virginia Small, Milwaukee Magazine, February 7, 2017

Master Plan for the Revitalization of Washington Park

An award-winning journalist, Virginia Small spent time in Washington Park while attending high school in Milwaukee. When she returned to her hometown in 2012 (after working in communications and journalism on the East Coast), she began writing and speaking about landscapes and environmental issues. She has led many tours of Olmsted parks in Milwaukee and other legacy landscapes.