Continuing the popular virtual discussion series, Conversations with Olmsted: Civil War, Abolition and the National Park Idea captivated an audience with exploration into Olmsted’s role in the creation of national public parks, encouraging the preservation of some of the United States’ most beautiful natural spaces.

The discussion was moderated by Olmsted 200 Honorary Committee Member Sara Zewde and featured Ethan Carr and Rolf Diamant. Carr and Diamant are the co-authors of a new book— Olmsted and Yosemite: Civil War, Abolition and the National Park Idea, which can be purchased here. Just in time for the bicentennial, the book examines the turbulent pre- and post-Civil War times when Olmsted designed Central Park and wrote the groundbreaking 1865 Yosemite Report. The authors explore Olmsted’s vision of public parks as “keystone institutions of a liberal democracy” and argue that Olmsted’s critical— now largely forgotten— role in the funding of national parks was “manipulated to erase references to an activist government working on behalf of freedom, civil rights, and the remaking of the republic.”

The provocative conversation stimulated a wide array of questions from viewers which could not be answered during the program time. In response to our dedicated audience, we are pleased to offer the following additional responses to thought-provoking questions:

Was there any link between the idea of allocating funding for public parks and allocating funding for land-grant colleges?

Rolf Diamant: Good question— absolutely! Like the Land-Grant College and Homestead Acts that preceded it, the Yosemite Act achieved a desired civic improvement by the granting of public land (much of it previously seized from Native Americans). In general, such civic improvements were opposed by slave interests and their Democratic representatives in Congress who believed such reforms might eventually undermine slavery and withdraw public lands from sale (an important source of revenue in lieu of taxation).

Let’s examine passage of the Yosemite Act, signed by President Lincoln in 1864, in the context of Justin Morrill’s first college land grant bill. In 1859, Morrill’s bill was denounced in apocalyptic terms by pro-slavery Southern Democrats and ultimately vetoed by President James Buchanan. There is little doubt that had the Yosemite legislation (a land grant) been introduced alongside Morrill’s bill in the ante-bellum Congress, it would have been subjected to the same rhetorical assault and suffered a similar fate.

Why would southern legislators be against public works projects that would benefit their constituents?

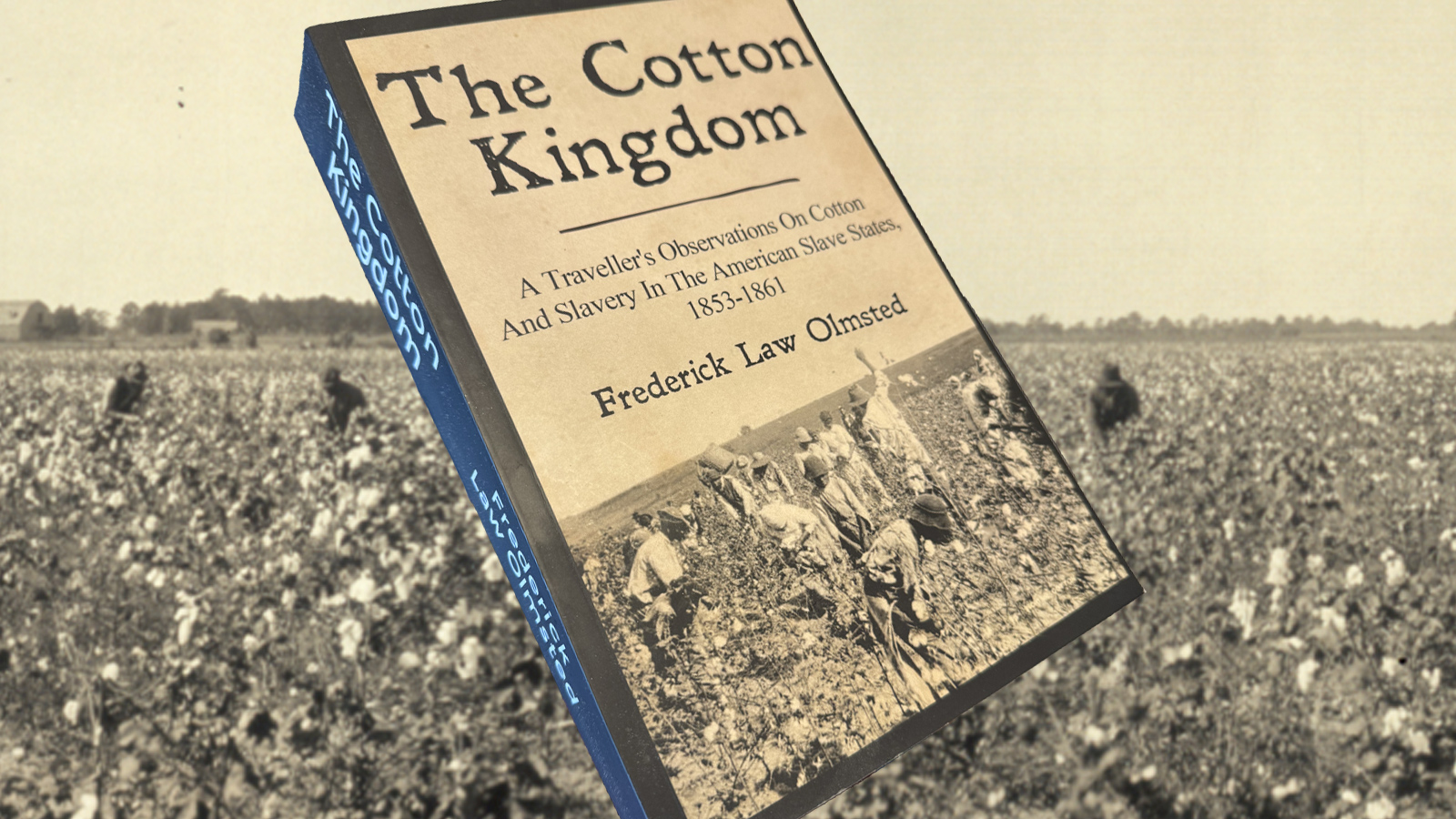

Rolf Diamant: There is no question, for example, that pre-war legislation that established a national system of land grant colleges would have benefited the families of farmers and mechanics of modest means — in the South, as well as the rest of the country. However, the political power structure in the South (dominated by slaveowners) that Olmsted wrote about in his dispatches for the NY Times, favored expanding economic investment in plantation slavery and cotton production— over competing civic needs and development— at a time when there was so much money being made (cotton made up sixty per cent of all US exports). In Congress, Southern Democrats (largely elected from the ranks of the planter class) also blocked any similar national initiatives that might have diverted public resources or posed in their view an existential threat to the slavery’s long-term future.

Did you miss our live stream? No worries— Conversations with Olmsted: Civil War, Abolition and the National Park Idea was recorded and is available on our YouTube here. Our other webinars are located here.

Please join us in May for the next installment in the Conversations with Olmsted series. Conversations with Olmsted: Olmsted and the Writing Life will be held on May 24 at 3 pm ET. Details and registration to come here.