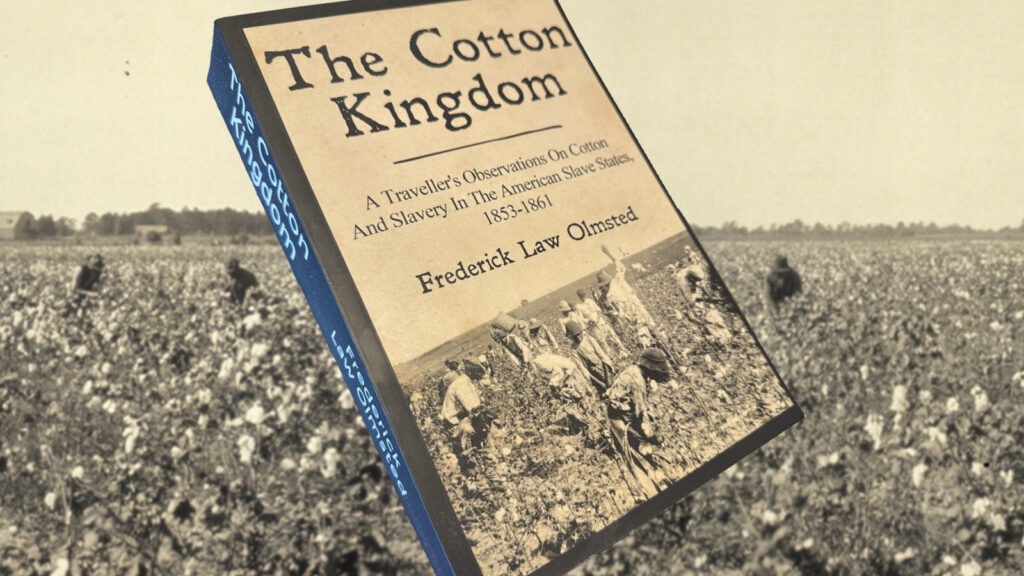

In December 1852, Frederick Law Olmsted began the first of two trips through the slaveholding South that lasted twelve months. He was 30 years old. He went for three reasons: he loved to travel; he was interested in learning about unfamiliar forms of agriculture; and he wanted to find out firsthand what slavery was like. He had been involved with recurring debates with his friend Charles Brace, and abolitionist and philanthropist. While Olmsted disliked slavery, he was also sympathetic to slaveholders; and he wanted to judge for himself rather than hear about slavery from Brace.

As Olmsted said of his trip, “I believed that much mischief had resulted from statements and descriptions” from abolitionists. “I had the most unquestioning faith, that while the fact of slavery imposed much unenviable duty upon the people of the South, and occasioned much inconvenience, the clear knowledge of which would lead to a disposition of forbearance” by northerners toward the south, and encourage a respectful purpose of assistance” in helping them with their “problem” of slavery. He went there thinking that slavery was “an unfortunate circumstance, for which the people of the South were in no wise to blame.” And he believed that “abolition there was no more practicable than the abrogation of hospitals, penitentiaries, and boarding-schools.” He traveled South hoping to illuminate “the peculiar virtues in the South,” which were “too little known or considered.”

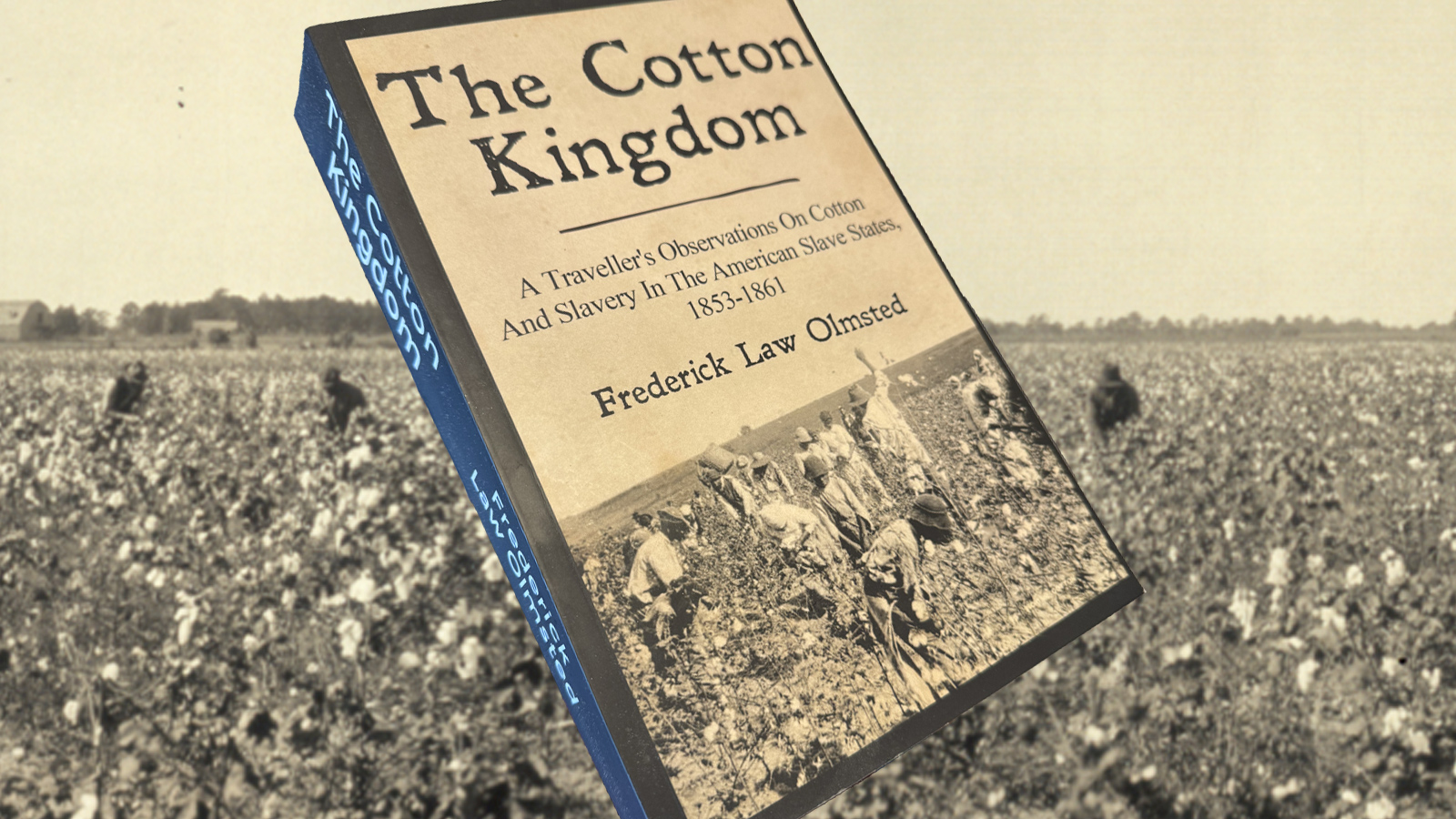

From February 1853 to June 1854, he published 65 letters for the New York Times describing his travels. Out of these letters came four books:

- “1856: A Journey in the Sea-Board Slave States”

- “1857: A Journey through Texas”

- “1860: A Journey in the Back Country”

- “1861: The Cotton Kingdom,” a two-volume book that revised and rearranged selections from “Seaboard States” and “Back Country.”

Olmsted went south skeptical of the movement to abolish slavery; he returned a reluctant abolitionist, his prior faith in Southern citizens shattered: “I was disappointed in the actual condition of the people of the South, citizen and slave,” he wrote after his first trip, and the more he traveled in the South, “the greater was my disappointment” in “the people of the South.”

Olmsted’s Southern writings constitute the most extensive and detailed description of the antebellum South by a contemporary observer. These works were part of a rich tradition of writers from the Revolution to the Civil War who traveled South to observe conditions there, saw firsthand the horrors of slavery, and vigorously critiqued the institution that girded the South’s culture and society. Most ex-slaves who published autobiographical accounts of their lives in a “slave narrative” cast the South as hell, slaveholders as devils, and the North as the promised land; and they end their narrative after reaching the promised land. There are also numerous examples of white writers—foreign and Northern—who took delight in ridiculing the inconsistency of freedom-touting slaveowners: Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur; Morris Birkbeck; Isaac Holmes; Frances Trollope; Alexis de Tocqueville; and Charles Dickens.

The nature of travel-writing about the south began to change after the Civil War. While black writers from Charles Chesnutt and W.E.B. Du Bois to Ida B. Wells, Zora Neale Hurston, and Gene Toomer continued to make sharp distinctions between the North and South, white writers sought to reconcile the differences between the regions in their quest for reunion. As the historian David Blight has noted, by the turn of the century, Northern and Southern whites looked back on the Civil War in terms that avoided ethical responsibility; neither side was good or evil, winner or loser. It was a stark contrast from the outset of secession, when each side fought for or against slavery, believed itself to be in the right, and invoked God’s aid against the other, as Lincoln famously said. Reconciliation erased the moral certitude of both sides. Whites ignored the cause of slavery, either as a positive good or as the sum of all evil, and explained the conflict in terms of amoral economic forces. By distorting and ignoring conceptions of evil, the reconciliation of the North and South fueled the rise of white supremacy, which greatly overshadowed the vision of emancipation and civil rights for blacks. Travel writing by whites participated in this reconciliation until World War II.

Throughout American history, travel writing has been enormously popular, and it has always had different purposes for different eras and peoples. Today, writing on the South has been of special interest to Northerners, often transplanted from the South, who continue to cast the region as a separate culture, a world apart.

Olmsted went South seeking knowledge; he returned with his worldview transformed. His southern trips revealed to him the close connection between the landscape and how people use, abuse, and inhabit it. The notion that identity— whether individual or regional— consisted of a continuous interaction between place and consciousness was a new concept in Olmsted’s day. It suggested that people could remake themselves through relocating, and it began the belief— still very much with us— that we can regenerate ourselves through travel. Change your place, and your understanding of yourself and your world also gets transformed. Olmsted understood very early that our physical landscape shapes who we are as much as we shape it. He brilliantly highlights this connection between place and identity in his southern writings; and the insight later fueled his interest in landscape architecture.

This blog post was originally published by the National Association for Olmsted Parks circa 2008. It was written by Harvard Professor John Stauffer regarding Olmsted’s trips to the South to research the institution of slavery. It resulted from Stauffer’s speaking engagement at a public discussion entitled, Looking Southward: The Southern Travelogue from Frederick Law Olmsted to the Present, that explored social conditions in the American South. Held on April 12, 2005, at the Boston Public Library Square, the discussion explored the American South’s society, economy and race relations through the keen eyes, perceptive minds and sharp pens of important travel writers of the past 150 years. Olmsted Papers Series Editor, Charles E. Beveridge, also served as a panelist at the forum that featured the writing of Olmsted who traveled to the South as a New York Daily Times special correspondent during the 1850s. The Olmsted Network (formerly the National Association for Olmsted Parks) and the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site were sponsors.