Designing landscapes is not a static process. Walking through a park or a campus, a visitor is experiencing the work of a multitude of decision makers, many of whom the original landscape architect never met. Mark Hough’s new book, Design Through Time, from the University of Virginia Press, explores this idea.

The illustrated volume offers case studies of parks, gardens, campuses, communities and cultural sites— from Prospect Park, the Missouri Botanical Garden and Mount Auburn Cemetery to Tuskegee University and Dumbarton Oaks Park— to answer several crucial questions: Whom is the proposed landscape conceived to please? How will it change, affected by both natural and societal events? How will stewards address the need for landscapes to remain relevant, attractive and accessible?

Recently, Hough, the university landscape architect for Duke University, was kind enough to answer several questions about his inspiration for the book and how he selected the landscapes he chose to feature.

Was there a particular landscape you watched evolve that inspired the book?

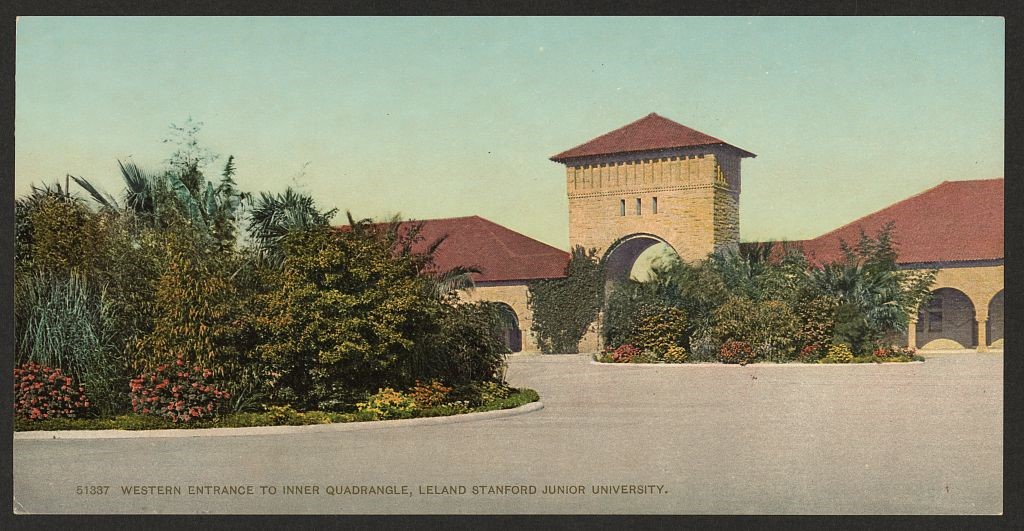

There are really two landscapes that inspired the book. The first is Central Park, where I worked in the 1990s in the design office at the Central Park Conservancy. This experience early in my career taught me that even the most sacred places need to adapt to meet the changing needs of communities, and it reframed how I think about and evaluate historic and public landscapes. It also influenced my work on the second landscape, the campus of Duke University, which was originally designed by the Olmsted Brothers firm and is where I have worked as the university landscape architect for almost 25 years.

Your book covers a wide range of landscapes across the country. How did you decide which ones to cover, and what was your research process?

My goal was to offer landscapes that convey a variety of scales, aesthetics, geographic locations and design legacies— some famous, others less so. A few I chose because I have admired them for many years, while others were ones I had been curious about or discovered have intriguing histories that fit well within the themes of the book. It was important to me that I personally visit each of the landscapes, a process that involved a lot of time walking sites, poring through archival information and interviewing a number of pertinent people who were generous with their time and added extra layers to the depth of the research.

Your subtitle refers to Prospect Park; what about its evolution as a public park made you want to include it?

I wanted to include at least one truly iconic place, and Prospect Park, regarded by many as Olmsted and Vaux’s masterpiece, surely enjoys that status. The challenges the park has faced over many decades, as it strives to respect its significant legacy while also allowing for needed adaptations and transformations, align well with my fundamental focus. I also have great respect for Tupper Thomas and Christian Zimmerman, whose work at the Prospect Park Alliance has been so critical to the ongoing success and continued relevancy of the park. To me, they epitomize the inherent value of stewardship and confirm the need for professionals who commit their careers to the betterment of a single landscape.

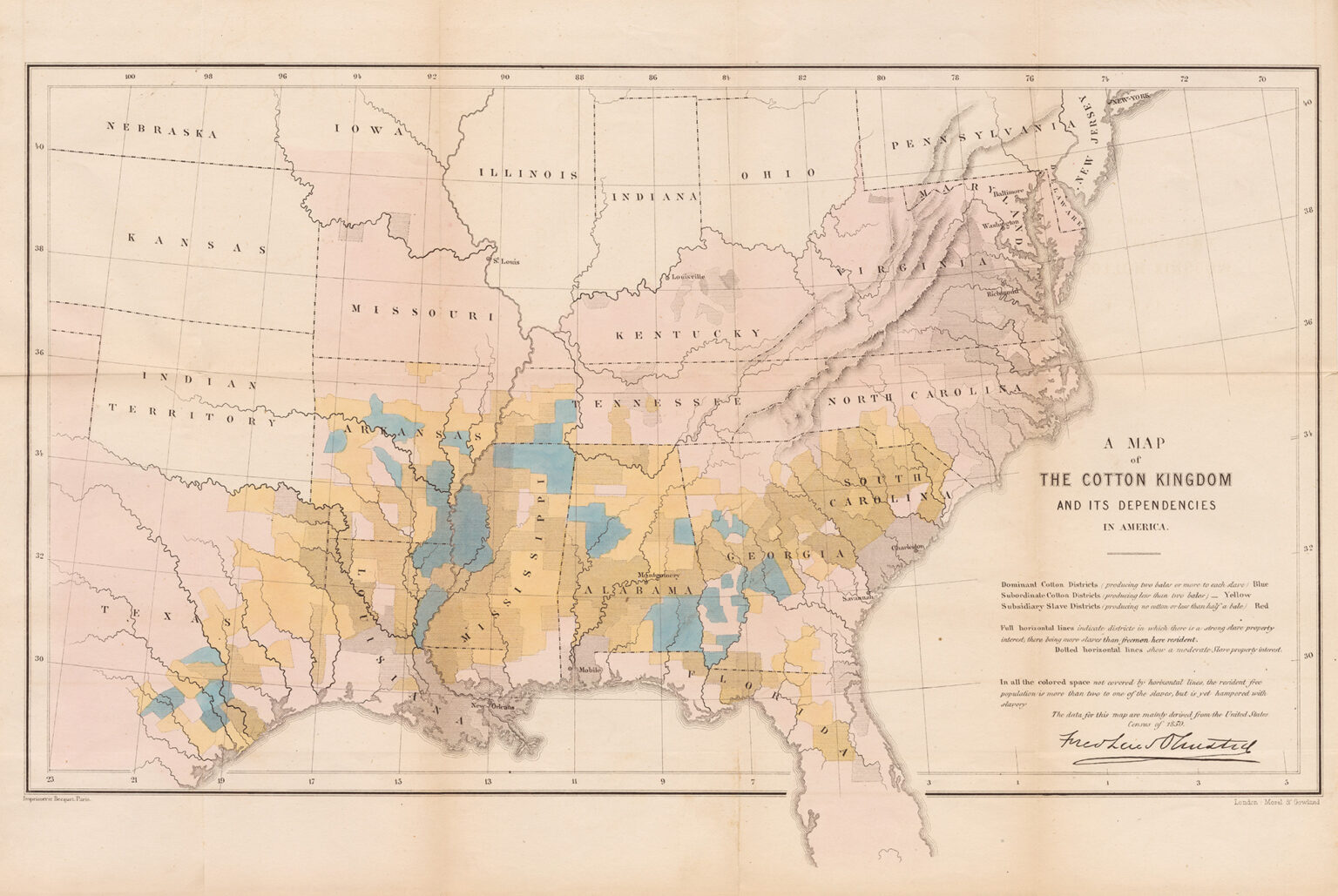

In describing your work to us, you said Olmsted’s influence “permeates through” the book. Please explain.

In addition to several of the book’s case studies that involve landscapes designed by Olmsted, nearly all of the landscapes I discuss have some connection to him or subsequent iterations of his firm. At Tuskegee University for instance, Booker T. Washington invited Olmsted to consult on the design of the campus, and David Williston, a landscape architect working for the university, took inspiration from Olmsted’s views on campus design and applied them to the grounds. In addition to this, Warren Manning, a protégé of Olmsted, completed a master plan for the university. This example, along with similar things I discovered from other places, affirmed for me just how pervasive Olmsted’s influence on America’s collective cultural landscape has been, even when only in an indirect way.

What is it about Olmsted’s influence that is so important for modern readers to understand?

I believe there is at least as much to learn from Olmsted’s prolific writings as from the plans and drawings generated by his firm. He was an exceptional writer, and his eloquent narratives describing the intent of his designs remain meaningful, informative and surprisingly relevant. This can be seen in his brilliant description of his and Vaux’s design intent for Prospect Park, which reads as a treatise on the critical need for urban parks and, in my opinion, should be considered required reading for landscape architecture students. At a time when the design process is increasingly dependent on rapidly advancing technologies, Olmsted’s old-school intellectual approach would be welcome in our attempts to create meaningful places able to stand the tests of time.

As the landscape architect for Duke University, how have you seen the campus change during your tenure?

The campus has been incredibly transformed. As part of a multi-billion-dollar expansion, we have created, reimagined or restored at least 125 acres of campus landscapes in collaboration with around 25 local, regional and national landscape architecture firms. This work includes the restoration of historic spaces designed by the Olmsted Brothers firm, as well as many new landscapes created to respect that heritage while inserting a contemporary layer into the campus. The cumulative results of this work have given me firsthand knowledge of how landscapes evolve and have both inspired and helped inform this book.

All photos by Mark Hough and used with permission.