Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. began his career as a landscape architect at an early age and achieved major professional accomplishments while still in his twenties. He also retained and renewed his father’s commitment to public service, and especially to the creation and stewardship of public parks. Olmsted, Jr. wrote the critical portions of the 1916 act creating the National Park Service, for example, which clarified that the “fundamental purpose” of national parks was “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such a manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” Throughout his career, Olmsted was actively engaged in shaping the policies of the national park system, particularly for Yosemite National Park. He also advocated for state and regional parks and planned the 40,000-acre “mountain park” system around metropolitan Denver beginning in 1912. But his greatest accomplishment in state park planning—and in fact one of the great accomplishments of his life—was the California state park survey, a portion of which is reprinted here.

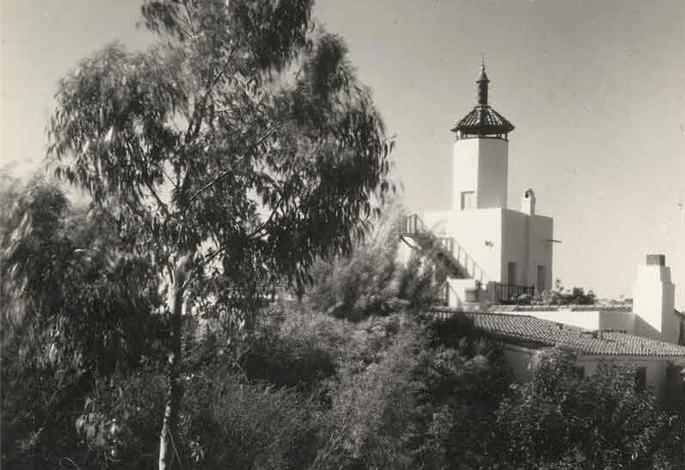

The movement to create state parks in California had begun earlier, mostly around concern for the remaining groves of Coast Redwoods. In 1927 the state legislature established a state park commission for the purpose of planning and developing a “comprehensive, state park system” as a means of “conserving and utilizing the scenic and recreational resources of the state.” The commission immediately hired Olmsted, who was already in California and well known to them as the designer of Palos Verdes Estates and other major subdivision projects in the state in the 1920s. Olmsted in turn consulted with leading California landscape architects, including Emerson Knight, H. W. Shepherd, and Daniel R. Hull.

The California state park survey demonstrated a new standard procedure for planning a diverse park and recreation system over a large and geographically varied area. The state was divided into districts, and for each district Olmsted recruited a committee of volunteers and experts in park design, forestry, history, and other fields. A state map was prepared at the University of California landscape architecture department that illustrated this comprehensive and scientific approach to the park planning through the use of color-coded zones corresponding to forest types and other information.

In what became an influential precedent for state park standards, Olmsted specified that each park should be “sufficiently distinctive and notable” to attract visitors from all parts of the state, not just the local area, and that the parks should also preserve characteristic forests, beaches, mountains, and generally a “wide and representative variety of [landscape] types for the state as a whole.” These types included desert parks and historical parks, as well as other landscapes that expanded the purposes and goals of scenic preservation and state park planning.

As Olmsted and his regional committees of volunteers surveyed the state for potential park sites in 1928, a massive advocacy campaign was underway to pass an historic state park bond act as well as to raise private donations for the acquisition of land. Passed in November 1928, the act allowed for the extensive implementation of Olmsted’s plans, resulting eventually in what many would consider the finest state park system in the country. Olmsted had worked himself into exhaustion and had employed himself and his staff at Olmsted Brothers at far below their regular fees; but the timing was fortuitous. Not only did the bond act pass in California overwhelmingly, but also four years later, as the National Park Service was launched into an intense expansion of its activities through President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the example and success of the California state park survey supplied a precedent and model for the creation and expansion of dozens of state park systems all over the United States. Today, many of those state park systems, including California’s, face unprecedented challenges to their funding and even to their continued existence. Olmsted’s assertion of the value of these “scenic and recreational resources,” and the spirit behind the campaign to plan, fund, and create state park systems, are needed today more than ever.