In the early twentieth century, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was a principal figure in establishing the profession of city planning. Between 1905 and 1915, he produced city planning reports for seven cities, including two at the request of the Pittsburgh Civic Commission. Olmsted was retained to suggest both immediate “necessary improvements and a comprehensive improvement program for the next twenty-five years.”

His 1910 study, PITTSBURGH: Main Thoroughfares and the Down Town District, included recommendations for upgrading and rationalizing the street system, proposals for public buildings and boulevards in the central city, and suggestions for improvements to primary residential and industrial districts. In addition to this vast undertaking, which addressed the renewal of older parts of the city, Olmsted broadened his charge to include suburban and regional planning. He advised the city’s leaders to look “to the wise and economical layout of what remains to be done, especially in the outskirts of the city where the major part of the city’s growth is bound to occur.”

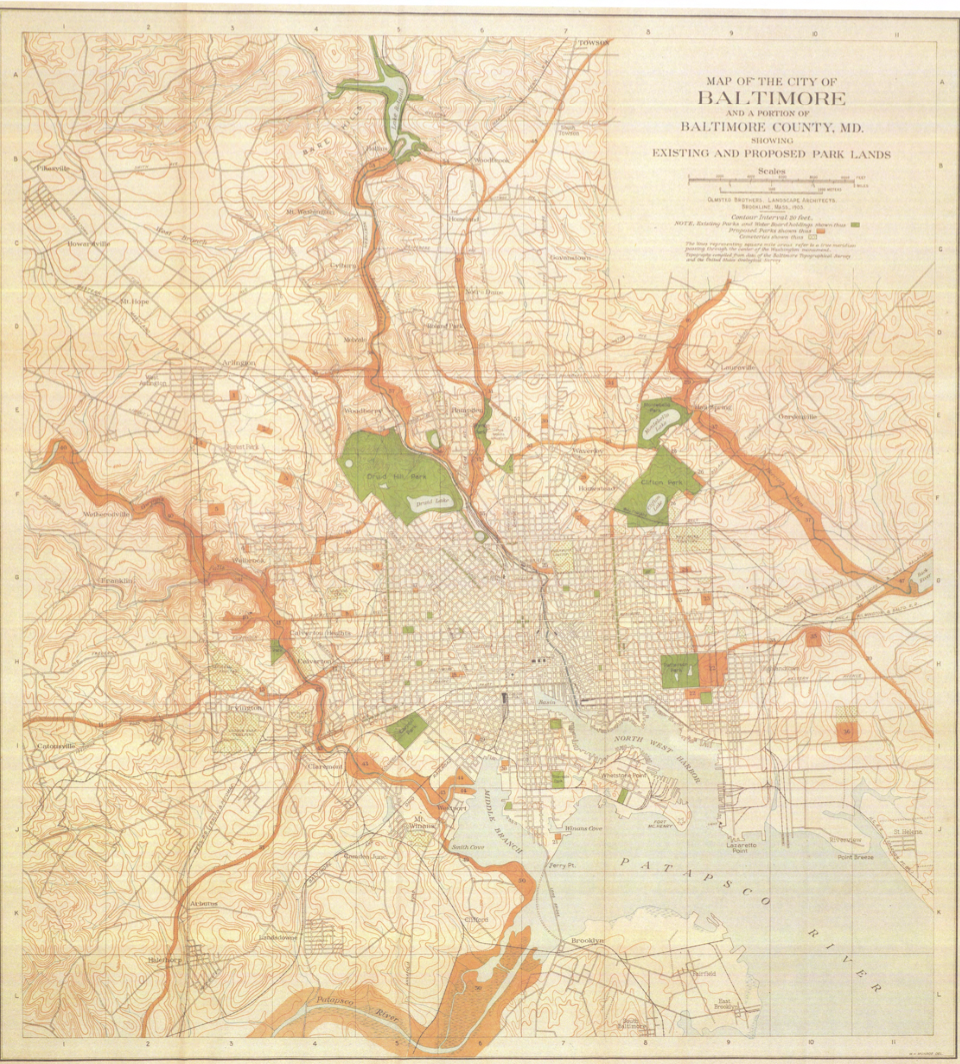

Prevention is cheaper than the cure, he admonished, and “the city plan is daily taking shape out of nothing, whether it is intelligently designed or not.” Olmsted recommended the creation of an administrative agency empowered to take a regional approach to planning, observing that the city was most likely to grow by the annexation of developing suburban areas. Olmsted’s city planning reports looked beyond matters of physical design and manipulation of the urban landscape to raise issues of social concern. From the time of his work on the 1901 McMillan Commission plan for Washington, D.C.’s monumental core, Olmsted’s city planning reports always included proposals for a network of park and recreation areas that should be accessible to all residents through parkways and public transportation.

In the following excerpt from the 1910 Pittsburgh report, Olmsted advocates for a park or playground within a quarter-mile of every home, a concept that became an important tenet of Progressive Era city planning and was popularized during the 1920s as the Neighborhood Unit concept. It was the city’s responsibility to provide parks, supervised playgrounds, libraries and field houses “that set a good example for the neighborhood” close by the homes of “children and women of the wage-earning families.” These citizens had the most need for healthful recreation and the least ability to travel to find it.

This selection illustrates Olmsted’s attention to the smallest detail. In addition to recommending a metropolitan street system, making proposals for a civic center, and designating far-flung parcels of land that could be linked into a regional park system, Olmsted thought deeply about the fine points of how the people would use neighborhood parks and what needed to be done to assure that they were able to enjoy them fully.