By the end of the nineteenth century, Spokane was a vital commercial and rail center for the flourishing inland region of the Columbia Basin. In addition to a scenic and healthful setting, the city had a group of progressive and ambitious citizens eager to see their municipality build on its advantages. None was more forward thinking than Aubrey L. White, the first president of the city’s new park board, who arranged for John Charles Olmsted’s first visit to the city in 1907.

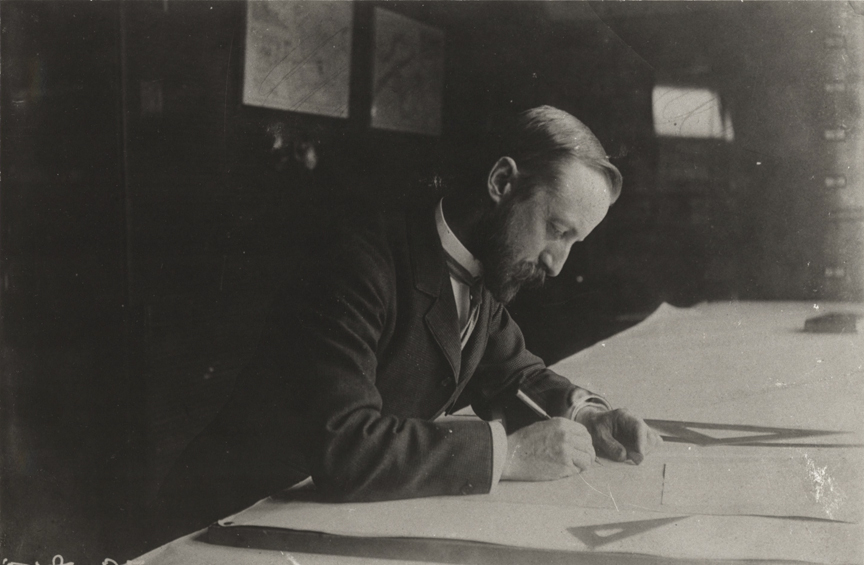

Olmsted was already deeply involved in his work in Seattle and Portland and elsewhere on the West Coast. He was familiar with the region and he could also arrange to pass through Spokane on his transcontinental train journeys. He did so several times between 1906 and 1908, once accompanied by James Frederick Dawson, an associate landscape architect of the firm. The Olmsted Brothers presented their report to the park board in 1908, although the commissioners chose not to publish it until 1913.

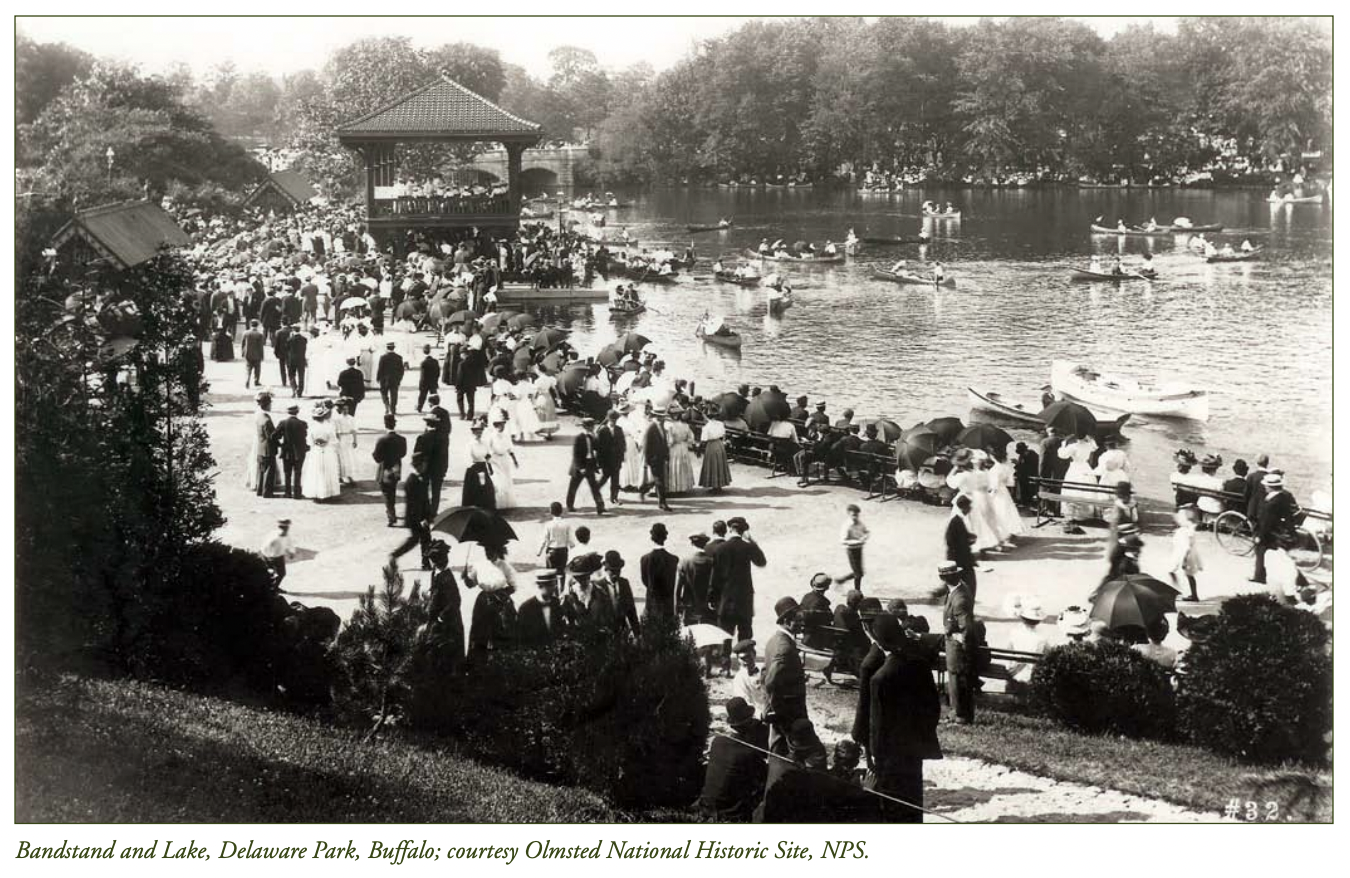

The Spokane report, like the Seattle report published three years earlier, is a mature statement of the goals and values of park-making that J. C. Olmsted learned from his famous stepfather in the nineteenth century, and then put forward anew for the twentieth. Working with younger associates and partners (Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. was almost twenty years younger), J. C. Olmsted had more extensive and personal experience working with the elder Olmsted than any other member of the firm. Above all J. C. Olmsted deeply believed in what he sometimes described as the “true purpose” of the large park—the country park—that was expansive enough to contain the broad effects of landscape scenery that could cause profound emotional responses, and therefore affect the emotional and physical well being of city dwellers.

He also knew that park advocacy, as well as planning, was always required, and that many members of the community would need to be convinced in order for such ambitious plans to be implemented. He therefore began the report with a classic statement of the need for parks, followed by another statement arguing specifically for the timely creation of four large parks, in addition to other small parks and playgrounds in Spokane. Historian Sally R. Reynolds observes that both plans and advocacy succeeded, and that under White’s leadership, the park board was able to implement most of the 1908 report’s recommendations over the next twelve years. “Not only was the Olmsted Plan implemented with few exceptions,” Reynolds concludes, “the park system has remained intact and has been added to, often in direct support of the original recommendations.”

The complete 1908 report is available as part of the 1913 Report of the Board of Commissioners being reissued in 2007 by the Spokane Parks Foundation as part of their park centennial commemorations.