In the 1950s and 1960s, Forest Hills Gardens was at its peak of maturity. The elms lining the streets had not yet succumbed to Dutch Elm disease and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.’s lush plantings surrounding the Tudor-inspired houses were at their peak. As a teenager living in the Gardens, I knew little about the history and significance of this unique place. The names “Olmsted” and sometimes “Atterbury” were batted around our dinner table, but meant nothing to me. I was more concerned about facing my nightly homework assignments. After ten idyllic years living on the South Shore of Long Island, we moved to Forest Hills Gardens in 1956, when I was fourteen years old. My father, a Wall Street lawyer, had grown tired of the long commute via the Long Island Railroad into Manhattan. On the other hand, my mother loved living on the “island,” as she called it, where she had a beautiful garden and a small greenhouse as well as lots of bridge-loving friends. I attended the local grade school and after-school activities consisted of riding my bike and waiting for the Good Humor truck to come jingling by. Summers were spent with overnight trips to Fire Island on our boat. It wasn’t until years later that I learned that Brightwaters, the seaside village where we lived, was an ideal planned community replete with swans on the lakes and grandiose homes.

When the decision was made to move back to the “city,” my mother was in tears and I was glum about leaving behind all my friends. To make matters worse, I learned that I was being sent to a private school rather than the local high school. Before Brightwaters, my parents had briefly lived on Union Turnpike in Forest Hills, but this time around it was “The Gardens,” the planned community conceived by the Russell Sage Foundation in 1909. Our new home was a picturesque attached row house on Ingram Street, not one of the grand mansions. It was actually quite spacious and well designed, with four bedrooms, a living room, dining room, sunporch (with a Baby Grand), a tiny kitchen (which my mother hated), and a postage-stamp-sized backyard. Later I learned that the house had been designed by the renowned architect Grosvenor Atterbury. My daily walk through the tree-lined streets with their quaint brick-and-stucco houses and Spanish tile roofs eventually led to the Kew-Forest School where the drill was quite different from the high school on Long Island. In sum, I had a lot of catching up to do.

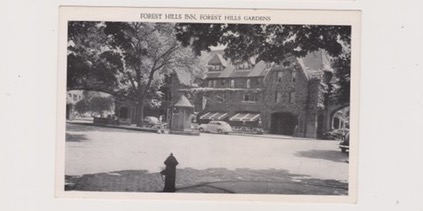

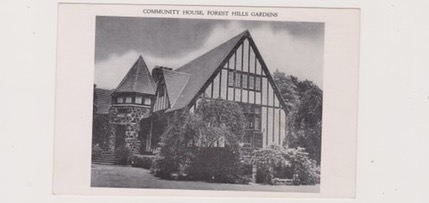

One of the perks of our new life was membership in the West Side Tennis Club (1912), where I proved to be a miserable player—miserable, in fact, in all sports. During these formative years, many pleasant hours were spent meandering the quaint streets in the Gardens admiring the homes and learning who lived in them, like Thelma Ritter on Greenway Terrace. On our way to events at the Community House, my girlfriends and I spun stories about the owners of some of the larger mansions. We took for granted the beautiful magnolias, dogwoods, and other ornamental trees lining the village streets, the exception being the sap-dripping Gingkos that spoiled my father’s Cadillac. At the time, of course, I didn’t realize how special these years were or how my exposure to the beauties of the Gardens sparked my interest in landscape history.

After his retirement in the early 1980s, my father was a legal advisor to the Forest Hills Gardens Corporation (successor to the Russell Sage Foundation) and one of his jobs was to “police” improvements by homeowners. We were regaled with tales of miscreants using the wrong paint color for exterior trim or, worse yet, replacing the tiny-paned louvered windows with picture windows. It was during these years that the names Olmsted and Atterbury began to mean something to me. And just in time, because I was beginning to discover the world of architecture and garden history and regularly visiting England where I was exposed to the Garden Suburbs that inspired the planning of Forest Hills Gardens. No doubt growing up in an elite designed community with grand houses, glorious trees, and impeccable maintenance opened the door to the world of landscape history.

Judith B Tankard is a landscape historian and the author of twelve books.