The elm tree was a pirate ship. Sometimes it was a castle. After school, I tossed my backpack by its trunk and clambered up its leafy branches. When darkness and mosquitos began to interrupt my play, I returned to the ominous-looking Victorian house across the street. It was in such a state of disrepair that neighborhood kids called it haunted. I called it home.

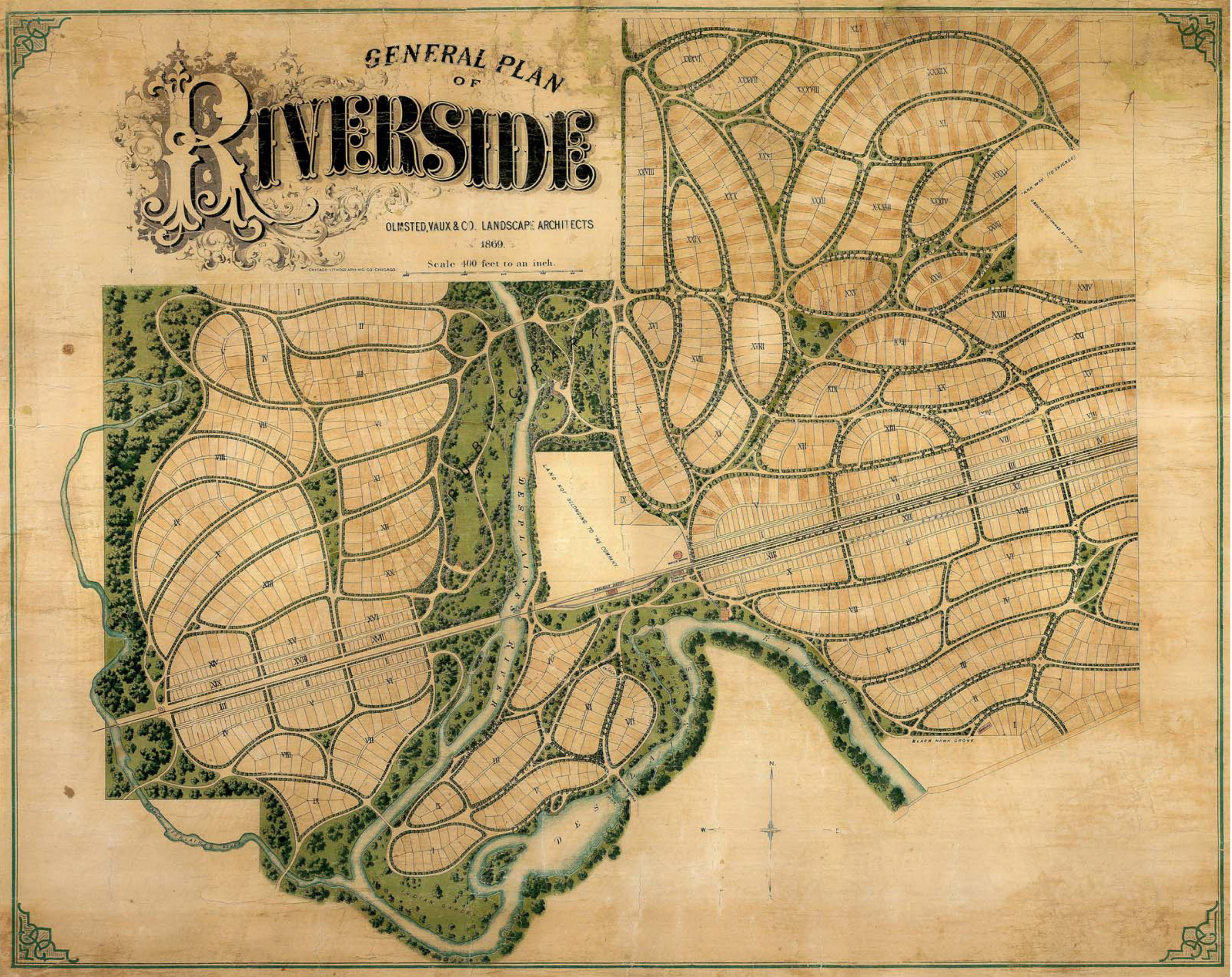

The elm tree was in the Akenside/Michaux Pocket Park, a tiny triangle of green space in Riverside, Ill. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, founders of American landscape architecture, were commissioned to design the village plan in 1868. Riverside’s defining characteristics include abundant greenery across its two square miles, gas streetlights that dot its winding streets and historically significant homes with large, sprawling lawns. This idyllic National Historic Landmark village is where I grew up climbing trees in the ‘90s.

My father so respected Frederick Law Olmsted that his was the first famous name I learned. Olmsted transformed swampy, unattractive swaths of land into beloved green spaces that were free and open to all. His first effort as chief architect for Manhattan’s Central Park was such a success that he went on to reshape America’s landscape. Though his partner Vaux was a talented draftsman and architect, Olmsted quickly surpassed him in notoriety. Olmsted designed hundreds of city parks, campuses, hospital grounds, cemeteries and more.

My dad revered Olmsted’s ability to transform outdoor spaces into living art. Dad also had an artistic vision. When my parents purchased the dilapidated Second Empire mansion in Riverside before I was born, it had every imaginable old house problem. They planned to restore it mostly themselves, using 19th-century salvaged materials and late-Victorian preservation techniques. We didn’t have the financial resources to hire architects, preservationists or contractors. Dad took on all those jobs himself, self-taught from books and on-the-job training.

Dad installed three antique street lights on our property, the same that dot Riverside’s streets. He selected earthy paint colors like Summerdale Gold and Country Redwood from a Victorian-era palette, meant to be harmonious with nature. He dug up the 100-foot concrete driveway to reinstate its original curve, then re-paved it with salvaged red bricks. It could be a coincidence that Olmsted had once undertaken a similar project at his Staten Island Farmhouse, where he first began experimenting with landscaping. Olmsted rerouted the carriage driveway so that it better conformed to his land’s topography, approaching the farmhouse in a gentle sweep, writes Justin Martin in Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted.

On the first page of a notebook where dad documented his house projects, he wrote: “A man who works with his hands is a laborer. A man who works with his hands and head is a craftsman. A man who works with his hands, head and heart is an artist.” Our house had been one of the first constructed in the early 1870s. Dad envisioned making it the gem of Riverside once again. In his mind, our house would be a work of art that blended seamlessly with Olmsted’s landscape around it. That is, if dad ever could ever finish the project.

Summers were always a flurry of activity, when my parents took vacation from their day jobs to work on the house. My friends took real vacations with their families or spent their summers at the members-only swim club. Left to entertain myself, I climbed the elm tree in the little park across the street. My favorite solo game was lost explorer. From my tree-top perch, I’d form my hands into the shape of an imaginary telescope and squint, peering for signs of civilization in the distance.

On the hottest days, I’d mosey along the winding Riverside streets to the air-conditioned public library. The half-mile journey should not have taken more than ten minutes. It took me an hour or more. There were so many four-leaf clovers to hunt, so many flowers to inspect, so many cavernous nooks in bushes to explore. As a nine-year-old in the ‘90s, I was experiencing Olmsted’s design exactly how he intended. “We should recommend for the general adoption, in the design of your roads, of gracefully-curved lines, generous spaces, the absence of sharp corners, the idea being to suggest and imply leisure, contemplativeness, and happy tranquility,” he wrote in the Preliminary Report upon the Proposed Suburban Village at Riverside, Near Chicago, published in 1868.

We should recommend for the general adoption, in the design of your roads, of gracefully curved lines, generous spaces, the absence of sharp corners, the idea being to suggest and imply leisure, contemplativeness, and happy tranquility.”

Frederick Law Olmsted, Preliminary Report Upon The Proposed Suburban Village At Riverside, Near Chicago

Olmsted’s 199th birthday this spring kicked off a year of events to celebrate his legacy leading up to the bicentennial celebration. If the Olmsted 200 programming doesn’t include the tiny triangle-shaped park where I spent my summers, I might host a solitary celebration of my own. I’ll pack a book and drive to where Akenside and Michaux Roads intersect. The elm tree with the sturdy climbing branches is gone, likely a victim to Dutch elm disease. A younger hackberry tree stands its place. I’ll toss my backpack by the trunk and lean against it. I’ll open my book. While others celebrate Frederick Law Olmsted’s better-known city parks and large-scale landscapes, I’ll sit in one little garden park underneath one tranquil tree, content.

Betsy Mikel is a Chicago-based writer with a lifelong passion for old houses. She grew up in a dilapidated Victorian in suburban Riverside that’s said to have been designed by William Le Baron Jenney. She is writing a memoir. Follow her at @akenside_house.