I’ve had a historian’s fascination with Olmsted for decades. No other American grappled with so many of the defining issues of the 19th century, including the abolition of slavery, the explosive growth of cities, and the degradation of the environment. Because so many of his concerns still are strikingly relevant, I once considered writing a book about him. But I’m glad I didn’t. Looking back, I see that my appreciation of Olmsted was purely intellectual until 2016, when I moved to Buffalo, New York. Now I live five minutes from the largest of the parks Olmsted and Calvert Vaux designed for Buffalo after the Civil War, and I walk there all the time. I often feel Olmsted’s presence.

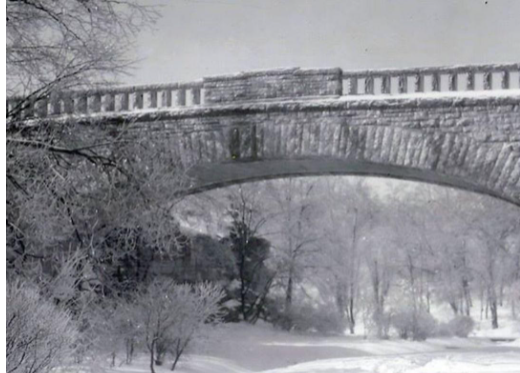

On my first walk in Delaware Park during the pandemic, I even spoke to Olmsted. Wary of any contact with strangers, I went out at dusk with snow falling, and I was overcome. The park was beautiful and serene and seemingly eternal, though I didn’t consciously think that. I just said, out loud, the only time I’ve ever talked to the dead, “Thank you, Olmsted!”

That night I began to think again about doing an Olmsted project. I felt a keenness, a passion, I hadn’t felt before. The result was a short “course” for Audible. My Audible course – “The Enduring Genius of Frederick Law Olmsted” – focuses on four questions that drove him both before and after he won renown as a landscape architect. In a highly mobile and individualistic society, what can create community? What enables cities to thrive? What kind of relationship to the non-human world is most satisfying and sustainable? What is government’s role in providing for the common good?

My walks in the park helped me reflect more deeply about all of those questions. That’s especially true of the question about community, which was critical to Olmsted’s mission as a landscape architect. Olmsted argued that parks were forces for social improvement. They could bridge divides of class and ethnicity. They could root people in place. Above all they could nurture what he called “communitiveness” – the understanding that we can’t be totally self-reliant, we depend on others, and we need to work with our neighbors to sustain our shared home. To be sure, some of Olmsted’s arguments now are dated. But I’m amazed by the many ways Delaware Park still is vital.

The park certainly is the most diverse place in the city. On my walks, I see people from around the world, in all manner of dress, of all ages, with many identities. And I see them at their freest. Not in the uniform of a job or in line as a customer, but being themselves. Though not a utopia, the park gives me hope that we can fulfill our dreams, together.

Adam Rome is professor of Environment and Sustainability at the University at Buffalo. His audio course about “The Enduring Genius of Frederick Law Olmsted” is available from Audible here.