Utica, a small community of 65,000 in the center of New York State, is sometimes characterized as a “rust belt city.” However objectively true this might be—it is indeed a place powerfully affected by deindustrialization—it is nevertheless also home to a relatively large array of architectural gems, and an Olmsted patrimony that is the bedrock of its impressive heritage.

Covering 600 acres, the Utica system of parks and parkways designed by the Olmsted Brothers Firm, is approximately 70% of the size of Central Park (for a city with 1/26th as many people as Manhattan), and it consists of three parks tied together by a three-mile-long parkway that gently winds across the southern end of the city. Civic-minded local patricians, the Proctors, envisioned this system and enlisted Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., in 1906, then heading Olmsted Brothers along with his stepbrother John Charles Olmsted, to make their vision a first-rate reality.

The Proctors also enlisted Olmsted Jr. to make Utica the subject of one of his first pioneering city planning reports (1908), which promoted the idea of creating a more robust system of parks for Utica. Before the Proctors began park-building in the 1890s, the city had only seven acres of public parkland, in contrast to the 700 it now has, comprised mostly of its Olmsted Brothers system.

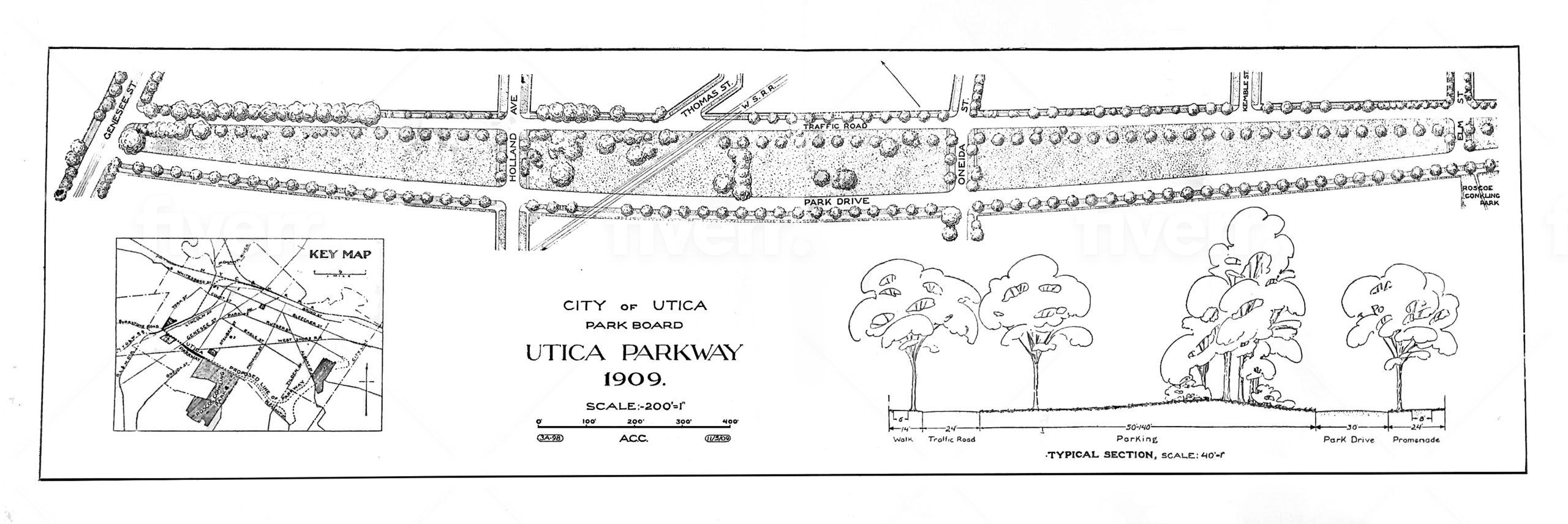

Utica’s Parkway covers 60 acres and was built in stages between 1909 and 1919. In the spirit of the then ascendant City Beautiful movement, the first half-mile of Utica’s Parkway was punctuated by monuments, mostly statues, selected at local initiative. Olmsted Jr. was not pleased with the location of the first monument on the parkway, the Swan Memorial Fountain, designed by the renowned American artist Frederic William MacMonnies. He had wanted to locate the foundation in Conkling Park, but his suggestion was ignored.

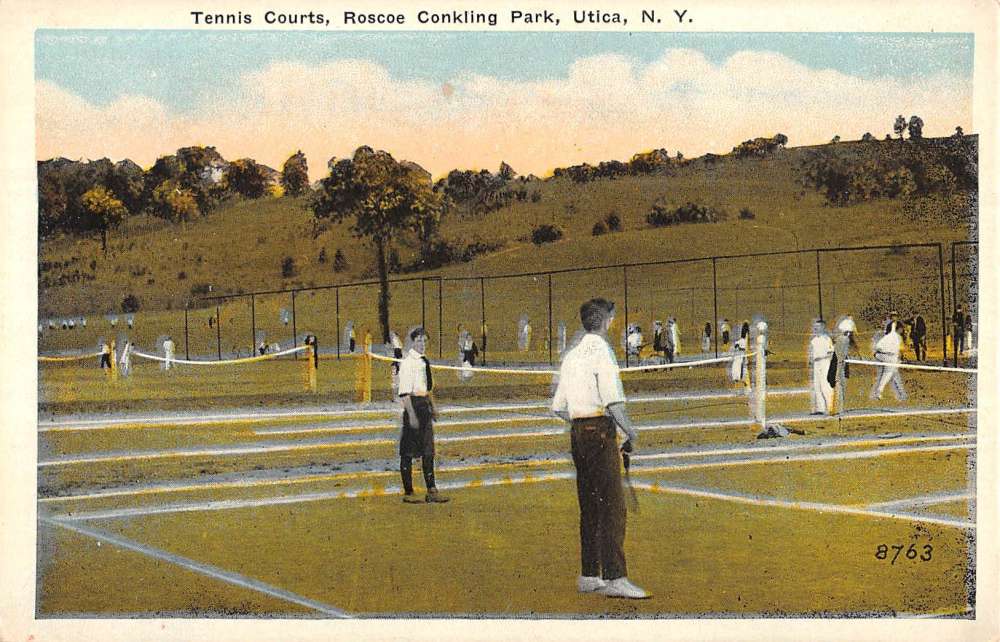

Roscoe Conkling Park, dedicated in 1909, has long been home to a municipal golf course (redesigned by Robert Trent Jones in the 1930s), tennis courts, and a zoo. Conkling Park is also home to a ski hill and chairlift of more recent construction (unfortunately not used much these days, thanks to climate change) and several promontories that – in Olmstedian fashion – offer majestic views of the Mohawk Valley. The best-known of these viewing areas is the site of The Eagle, an imposing sculpture created by Charles Keck (who also created the relief sculptures on Manhattan’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel, among other accomplishments).

The gem of the system is F.T. Proctor Park. Built in 1912-14, it is 62 acres built around a gently rolling meadow largely covered by wild thyme. Original features include the so-called Lily Pond, a formal rectangular pool designed by Olmsted Jr. in 1913, a formal gate of gray granite, and a picturesque ravine.

Utica’s Olmsted heritage does not end in Proctor Park, however. It includes five neighborhoods designed by Olmsted Brothers: Brookside Park, Proctor Boulevard, Talcott Road, Sherman Gardens, and Ridgewood. These neighborhoods were laid out largely as designed between 1913 and 1926. Today, most have a mixture of architectural styles. The Great Depression interrupted development of several of these neighborhoods (notably the two largest, Ridgewood and Sherman Gardens), resulting in varied periods of construction in the 1920s, 1930s, and the immediate postwar period, in addition to some construction in the 1960s and 1970s. There is also one partially-realized but beautiful Olmsted-designed neighborhood, Oxford Heights (better known as Hoffman Road, for the part that was completed), in the adjacent suburban village of New Hartford. The Olmsted Brothers firm was active in this community, mostly designing landscapes for individual homes, into the 1940s.

Utica’s Olmsted-designed parks and parkway system and neighborhoods cover about a tenth of the land mass of this little city. This is complemented by a string of larger structures built on Genesee Street, Utica’s main historic north-south artery, built during Utica’s “Olmsted Era” (1900-40) and designed by architects of stature at least broadly comparable to that of Olmsted Brothers, most notably: Ralph Adams Cram, Carrère and Hastings, Thomas Lamb, York & Sawyer, and Alfred Fellheimer.

Olmsted City of Greater Utica, a new program of the Landmarks Society of Greater Utica (this community’s historic preservation advocate for fifty years) is working to raise awareness about Utica’s Olmsted and Olmsted-era treasures. Its work currently focuses on public education and the restoration of F.T. Proctor Park in time for the Park’s centennial, in 2023, of its donation to the people of Utica. It is our hope that Utica will earn recognition as an “Olmsted City,” and it eagerly looks forward to contributing to the impending Olmsted 200 celebration.

Philip Bean is the director of Olmsted City of Greater Utica, a program of the Landmarks Society of Greater Utica, members of the Olmsted Network and celebration partners of Olmsted 200.