Olmsted’s Three Visions for Jackson Park

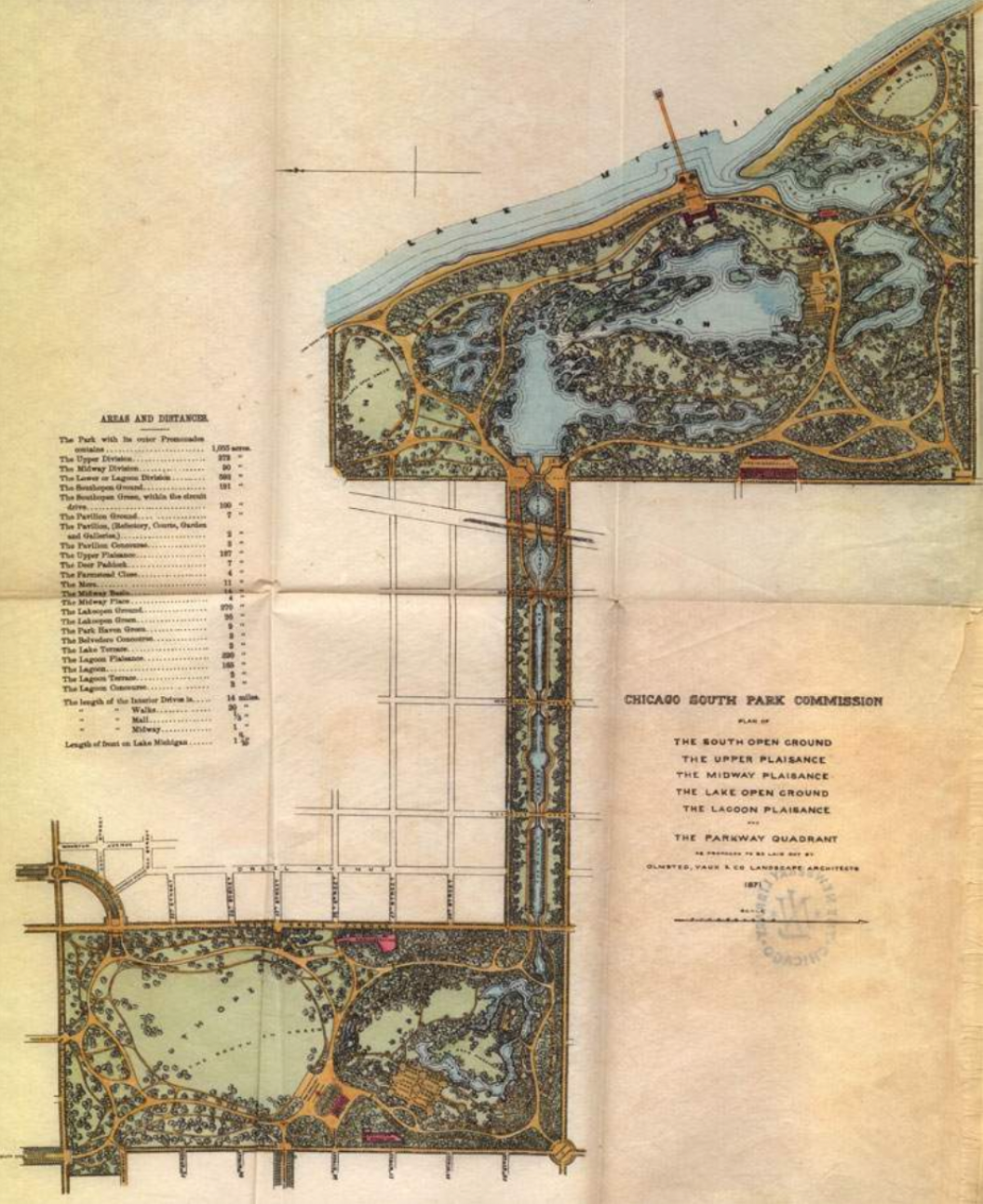

Vision One: Chicago’s South Park

In Chicago, Frederick Law Olmsted and his partner Calvert Vaux originally laid out the 1055-acre South Park, later known as Jackson and Washington Parks and the Midway Plaisance, 1871. The park was created and managed by the South Park Commission (SPC), one of three separate park districts chartered by State legislation in 1869. Although the South, West, and Lincoln Park Commissions were independent agencies, the overall goal was to create a unified and interlinking ribbon of parks and boulevards that would encircle Chicago. Ultimately, the Olmsted firm was involved only in designing parks for the South Park System.

In May of 1869, while Frederick Law Olmsted was in the area working on the Riverside, IL commission, members of the SPC asked him to visit the proposed site. Although Olmsted was known for recognizing “the genius of a place,” and designing scenery that enhanced those qualities, he was less than pleased when he saw Chicago’s South Park site.[1] In fact, when referring to the natural conditions of the site, Olmsted stated that “if a search had been made for the least park-like grounds within miles of the city, nothing better meeting that description could have been found.”[2]

Despite Olmsted’s initial disappointment with the site, he and Calvert Vaux created an impressive original plan in May 1871 that would transform the unimproved grounds into a magnificent landscape.

This plan includes a 38-page written report that explains the designers’ intentions in a detailed and poetic manner. The plan divides the park into three areas, the 372-acre Western or Upper Division, which became known as Washington Park, the 593-acre Eastern or Lower Division, later renamed Jackson Park, and the 90-acre Midway Plaisance—a grand boulevard linking the two large landscapes.

Olmsted felt disdainful of the site’s flat and marshy natural conditions, but he believed that it had one great asset— its relationship with Lake Michigan. He admired the lake’s “special grandeur” and suggested that the “Lake, can be made by artificial means no more grand or sublime.”[3] Using water as a unifying theme, Olmsted’s plan connected the Eastern Division to Lake Michigan through an intricate series of lagoons with lushly planted islands and edges, meant to inspire a sense of awe and mystery for park patrons.

Boats entering at Lake Michigan could navigate through the lagoons of the Eastern Division (Jackson Park), and, if the plan had been fully implemented, the boats could have cruised along a formal canal through the center of the Midway Plaisance, to enter a small lake, called the Mere in the Western Division (Washington Park). In the early years of park development, construction of the canal had to be put on hold, and though there was a later attempt to build it, the Midway canal was never realized.

The impact of the Great Fire of 1871 and problems with land acquisition delayed the implementation of Olmsted & Vaux’s plan, particularly in the Eastern Division. Responding to financial challenges, the commissioners constructed the park in phases. They hired Horace W.S. Cleveland to begin landscape improvements, focusing first on the Western Division— Washington Park.

Vision Two: 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition

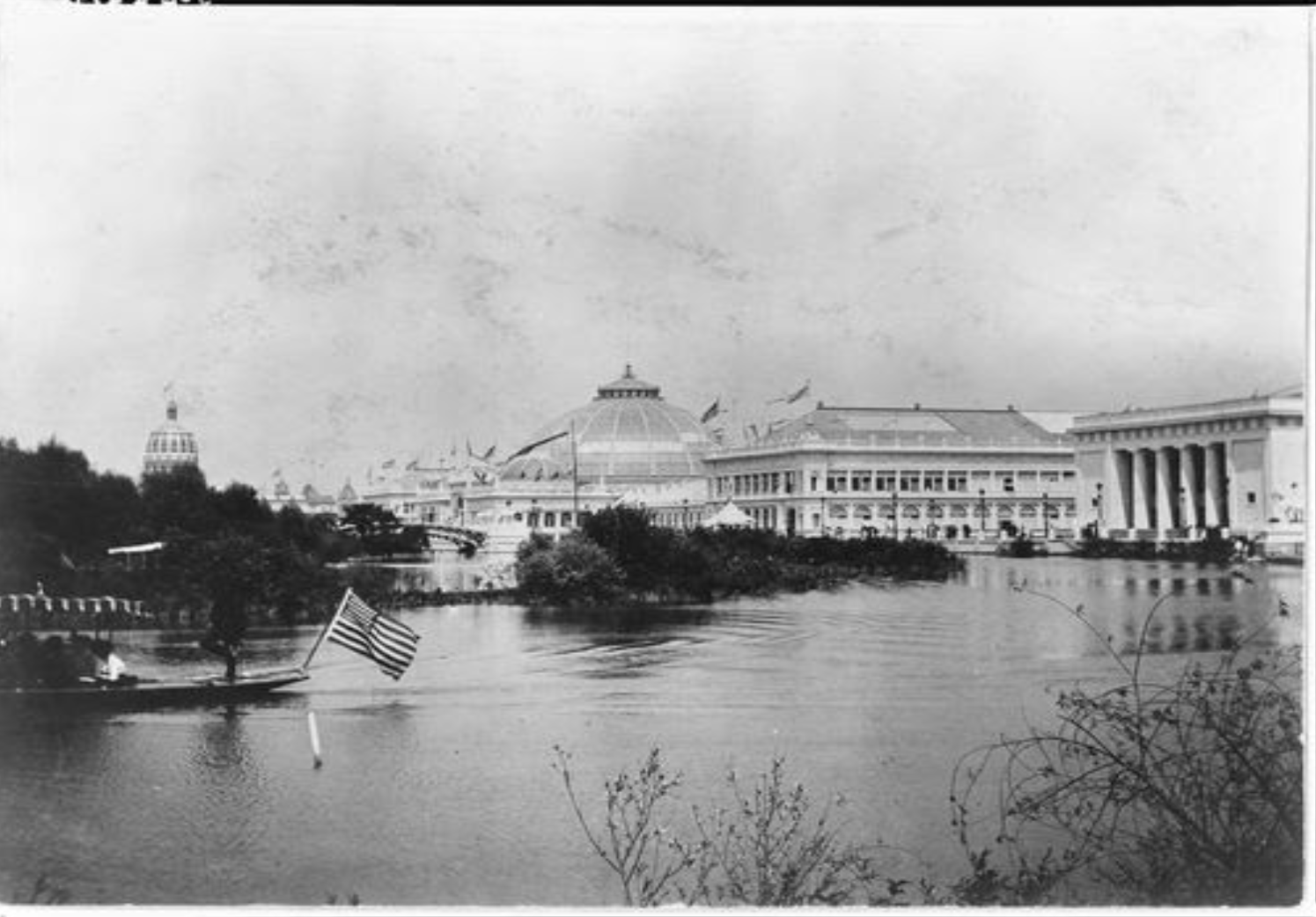

Two decades later, Olmsted had the opportunity to create a second plan for Jackson Park, and this time his grand vision was fully implemented. Literally rising from the ashes after the Fire, Chicago was selected as the site for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Olmsted was asked to help select the location of the fairgrounds. Stressing that views of Lake Michigan should provide the backdrop for the fair and noting the unfinished state of Jackson Park, he recommended holding the exposition there.

Olmsted and a young associate, Henry Codman, designed the fairgrounds in collaboration with Chicago architects Daniel H. Burnham and John Wellborn Root. The designers explained that after making many sketches, “on a crude plot” of a “large scale, the whole scheme was rapidly drawn on brown paper” and that this plot “contemplated as leading features of design”:[5]

That there should be a great architectural court with a body of water therein; that this court should serve as a suitably dignified and impressive entrance hall to the Exposition, and that visitors arriving by train or boat should all pass through it; that there should be a formal canal leading northward from this court to a series of broader waters of a lagoon character, by which nearly the entire site would be penetrated, so that the principal Exposition buildings would each have a water, as well as a land frontage, and would be approachable by boats; that near the middle of this lagoon system there should be an island, about fifteen acres in area, in which there would be clusters of the largest trees growing upon the site; that this island should be free from conspicuous buildings and that it should have a generally secluded, naturally sylvan aspect.[6]

Frederick Law Olmsted

A group of highly talented architects and artists created the buildings and sculptures of the fair. Most structures were rendered in a classical style and whitewashed to further unify the fairgrounds.

Olmsted wanted to keep the Wooded Island free of buildings or other objects. He felt that the calm “naturalness” would “serve as a foil to the artificial grandeur and sumptuousness” of other parts of the fairgrounds.[7] Despite this intent, there were many requests for pavilions and other amenities on the island. With these pressures, the designers asked themselves, “which of all the propositions urged” would have “the least intrusive and disquieting result?”[8]

One of the requests—a pavilion on the Wooded Island— came from the Japanese government. The proposal was to build a structure inspired by an ancient Phoenix temple. Olmsted and Burnham decided that the elegant and simple Japanese Pavilion known as the Ho-oh-dean would not interfere with the natural appearance of the island.

During a six-month period in 1893, the World’s Columbian Exposition dazzled an estimated 27 million visitors. Beginning in January of 1894, a series of fires destroyed many of the fair buildings. Later that year, the Chicago Salvage and Wrecking Company was hired to demolish most of the remaining structures.

Vision Three: 1895 Olmsted, Olmsted & Elliot Plan to Transform Jackson Park Back to Parkland

After the fair, the SPC hired Olmsted’s firm, then known as Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot, to transform Jackson Park back into parkland. The fairgrounds had always been planned as a temporary installation. The Commissioners wanted to create a beautiful site that “would retain many of the features characteristic of the landscape design of the World’s Fair” while also providing a “modern park” with facilities “for refined and enlightened recreation and exercise.”[9]

Olmsted’s 1895 Plan included “three principal elements of the scenery” for Jackson Park, “the Lake,” “the Fields,” and “the Lagoons.”[10] The plan fully capitalized on views of Lake Michigan for people walking, boating, driving, and riding. As had been included in the two earlier plans, sequential and interconnected lagoons offered changing landscape scenes, as well as access by boats throughout the entire waterway. There were walkways near the water and scenic overlooks. But now, the canal of the exposition grounds would be replaced with informal and naturalistic lagoons. The green lawn areas of “the Fields” would stand in contrast to the lake shore and lagoon scenery and would provide democratic spaces for lawn tennis and other games.

In addition to the three principal elements, the plan retained two important buildings from the World’s Columbian Exposition – the Fine Arts Palace and the Japanese Pavilion. The Fine Arts Palace became the Field Columbian Museum in 1895 and later transformed into the Museum of Science and Industry. The Japanese Pavilion— with a garden added in the 1930s— proved to be and iconic example of Japanese architecture and gardens until a tragic loss to fire in 1946. Today, the museum, Japanese Garden, and a commemorative version of Statue of the Republic— dedicated in 1918— are visual reminders of Jackson Park’s history. Though more subtle, but equally beautiful, are lagoons, historic bridges, winding paths, and the Wooded Island– all features that reflect Olmsted’s legacy in Chicago.

Julia Bachrach is the former historian of the Chicago Parks Department and author of “The City in a Garden: A Photographic History of Chicago’s Parks.”

[1] Charles E. Beveridge, “Olmsted— His Essential Theory,” National Association for Olmsted Parks, http://www.olmsted.org/the-olmsted-legacy/olmsted-theory-and-design-principles/olmsted-his-essential-theory.

[2] Olmsted, Frederick Law. “The Landscape Architecture of the World’s Columbian Exposition.” Inland Architect 22, no. 2 (September 1893), p. 19.

[3] Olmsted, Vaux & Co., Landscape Architects. Report Accompanying Plan for Laying Out the South Park, South Park Commission, 1871, p. 10.

[4] Ibid, p. 9, p. 16.

[5]Olmsted, Frederick Law. “The Landscape Architecture of the World’s Columbian Exposition, p. 20.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Jackson Park, Chicago,” Park and Cemetery, Vol. V., No. 2, April, 1895, p. 20.[10]Revised General Plan for Jackson Park, Olmsted, Olmsted & Elliot, 1895.