Are you one of the hundreds of thousands of people who read Erik Larson’s best-selling book, The Devil in the White City?

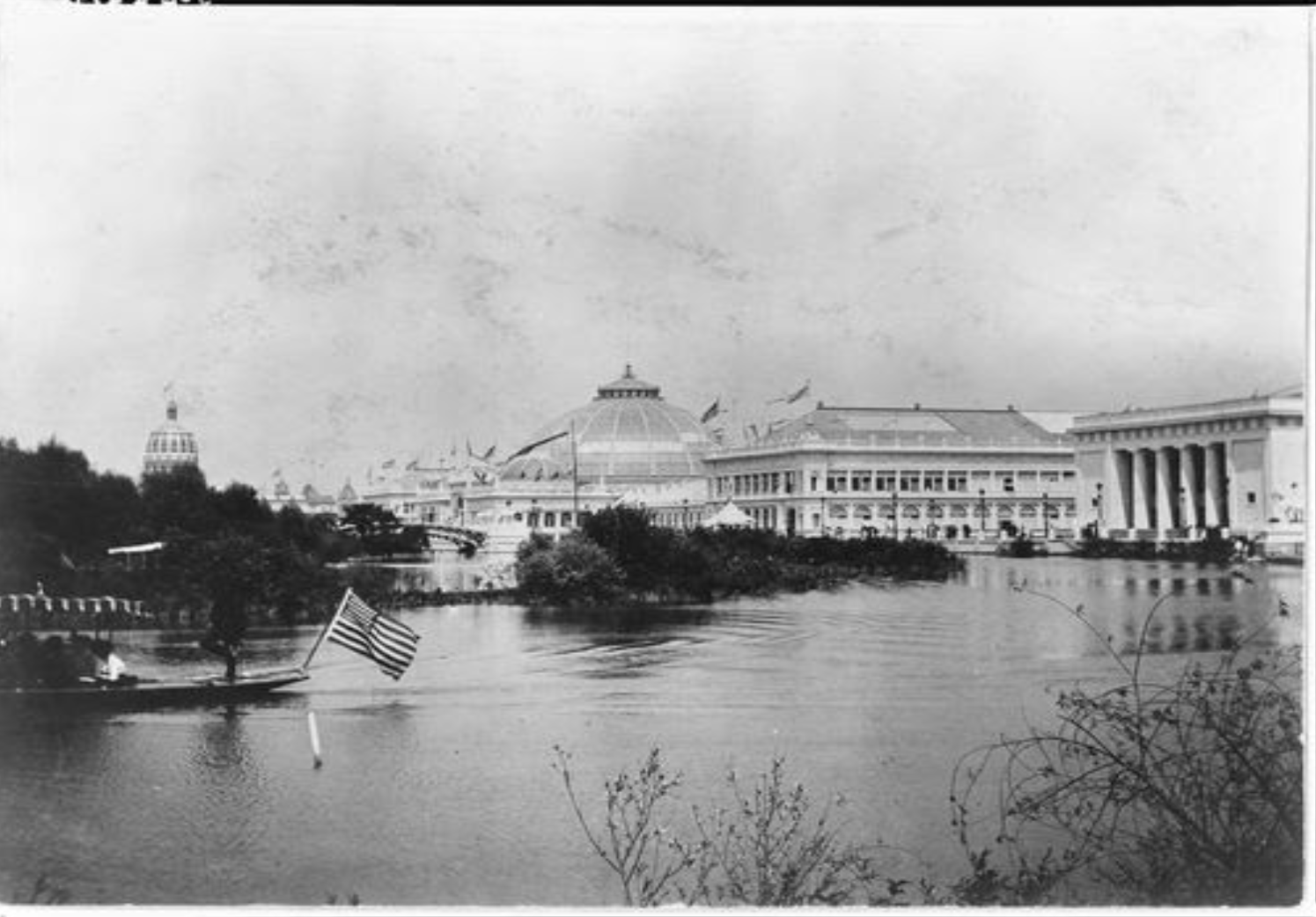

If so, you probably remember the vile serial killer, H. H. Holmes, who is central to Larson’s mesmerizing story. But do you also remember Daniel Burnham and Frederick Law Olmsted? They were responsible for creating “the White City” and overseeing the development and design of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park.

The Windy City out-competed others to win Congressional approval to showcase the Midwest—and show up the French who had debuted the Eiffel Tower at the 1889 Paris Exhibition. Chicago leaders wanted to put their city on the map, and 28.5 million visits later —representing almost half the U.S. domestic population in 1893—they had.

Leading the charge for the design of the World Fair was architect Burnham. He was a force of nature, and someone who believed it was important to “make no little plans. They have no magic to stir a man’s blood.”

As Director of Works, Burnham brought a grand vision. The fair included about 200 buildings and exhibits, but at its center was a core of buildings, a “White City,” composed of an array of glistening white buildings devised to house the exhibitions.

Working closely with Burnham was Olmsted, who near the end of his career, was responsible for the landscape design. He helped select the Exhibition location and converted the swamp into lagoons and a glorious wooded island with lush verdure to be enjoyed from the water. Having experienced life on the ocean during his year-long service in the China Trade, Olmsted had a particular interest in ensuring a memorable boating experience.

While the World Fair proved to be a great success, its creation was nothing short of herculean.

The world was swept up in the Panic of 1893, a major economic depression. The exposition was running behind schedule and the landscape design offered special challenges. Plant nurseries had little to offer in a short timeframe, so Olmsted determined that it was best to collect native plant materials from streams and swamps around Chicago. In a report to the American Institute of Architects, Olmsted recounted collecting over one million plants, and then planting the lagoons with 100,000 “willows, seventy-five large railway platform car-loads of herbaceous aquatic plants, and 140,000 ‘other aquatic plants, largely native and Japanese irises,’ with 285,000 ferns and other perennial herbaceous plants.”(p. 475)

Quite frankly, Olmsted was none too fond of the white buildings. His hope was to employ the landscape to soften the visitor’s experience and to connect city residents with the rejuvenating and healthful benefits of nature. As Olmsted explained it, the goal of the landscape design was “to establish a considerable extent of broad and apparently natural scenery, in contemplation of which a degree of quieting influence will be had, counteractive to the effect of artificial grandeur and the crowds, pomp, splendor and bustle of the rest of the Exposition.”

Contemporaneous accounts indicate Olmsted succeeded. The wooded island met with considerable applause and is still enjoyed today.

At the close of the fair, the exhibit buildings were removed. Olmsted and his son, John Charles, traveled back to Chicago to return Jackson Park to its original design. They wanted to ensure open vistas to the lakeshore and a pristine experience of nature for future generations. They were explicit that the Science and Industry Building was to be the highest and only structure so that building would not overpower the landscape.

In a passionate essay, The Spoils of the Park, Olmsted made it clear that buildings were antithetical to his park design and he railed at politicians and public officials who viewed parks as simply places to build. Olmsted explained, “The very ‘reason for being’ of the Park is …opportunity for pleasurable and soothing relief from building…. Where building for other purposes begins, then the Park ends. The reservoirs and the museum are not part of the Park proper: they are deductions from it.”

Olmsted was regularly disappointed by “degradation of [his] works…the breaking of promises to the future which had been to me as churchly vows.” He urged officials to find alternatives to destroying a park’s natural setting—its unique vistas and open green space—by adding intrusive architecture.

Today, the Obama Foundation is making plans to construct the Obama Presidential Center in Jackson Park. Olmsted would surely view the Foundation‘s plans as one more “broken promise” to the future.

Dede Petri is the president of the National Association for Olmsted Parks.