From the beginning of his career, Frederick Law Olmsted had a clear concept of what constituted a “park,” and he devoted much time and energy to explaining the difference between a park and other types of public recreation grounds. The purpose of a park was to provide city dwellers with an experience of extended space that would counteract the enclosure of the city by providing “a sense of enlarged freedom.” An expanse of meadow with gracefully contoured terrain, gently curving paths and an indefinite boundary of trees was the central element of the park. Every city, he was convinced, needed such a freely accessible public space. It would provide the most effective antidote to the debilitating artificiality of the built city and the stress of urban life. The park made possible what he termed “unconscious” recreation, whereby the visitor achieved a musing state, immersed in the charm of naturalistic scenery that acted on the deepest elements of the psyche. There the visitor could experience an “unbending” of the faculties that would restore mental and physical energies, renewing strength for the daily exchange of services that sustained the community of the city. This public space would serve a variety of different activities for groups of visitors, with no group or activity monopolizing any part of it. To achieve this, all design details were rigorously subordinated to promote the psychological effect of the park space, by a means that Olmsted called “the art to conceal art.”

Olmsted believed that in a park, in addition to restorative landscape, “the largest provision is required for the human presence.” He planned extensive systems of walks and drives for visitors, and designed sections of his parks for the gathering and entertainment of crowds. There were places for civic gatherings, for music concerts and for promenades. There were refectories for providing food and beverages and facilities for children’s play and gymnastics. Through the years, as team sports became more popular, there was provision for them as well, in separate areas that avoided an “incongruous mixture” of uses and left the landscape experience undisturbed. The separation of interior ways—drives, paths and bridle paths—from each other, and of cross-park city traffic from the park’s circulation system, also strengthened the landscape experience.

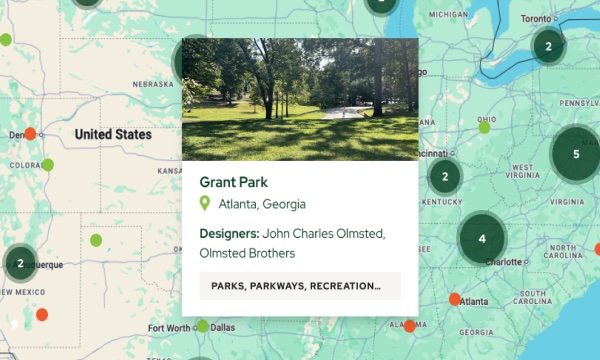

A corollary design principle was the provision for active sports and crowd activities in separate spaces at a distance from the principal park of the city. The purpose was to supply a number of all-city uses, not a series of merely local recreation grounds. Such a system of parks and recreation grounds, first clearly accomplished in Buffalo, New York, created a structure of green spaces in advance of the concentrated settlement of residential areas. Completing this system were ribbons of public space in the form of parkways that facilitated movement through the city and served as neighborhood outdoor resting places. Usually two hundred feet wide, the parkways separated the commercial traffic of carts and wagons from private carriages, and provided separate ways for pedestrians and equestrians. Olmsted also advocated creation of linear greenways along urban stream valleys. The classic example is the valley of the Muddy River between the Charles River and Jamaica Pond in Boston and Brookline, Massachusetts.

Olmsted also urged public ownership of areas of special scenic beauty and the creation of scenic reservations where the principal role of the landscape architect was to construct a circulation system that would facilitate enjoyment of the scenery with least intrusion on it. During the twenty-five years between the retirement of Frederick Law Olmsted and the death of John Charles Olmsted, the firm designed extensive park systems for many cities. After the 1920s, the Olmsted firm created few parks of the size created by the earlier firm, and with more emphasis on utilizing urban stream valleys. In its later years, the firm also placed much greater emphasis on local parks that provided active facilities, including the fieldhouses that marked the Progressive Era, and facilities for team sports. In several instances this involved planning areas for recreational athletic fields adjacent to older city parks. The decades of the 1920s and 1930s saw Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and other firm members carry out extensive and innovative work in county, state and national park planning and scenic preservation.