The design of residential grounds constituted the largest category of projects for the Olmsted firm over the entirety of its practice, with more than 3,000 listings, of which about 2,000 generated at least one plan. Although parks and park systems were initially the major area of endeavor for Frederick Law Olmsted and his partners, domestic design increasingly became an important component of the practice as transportation improvements extended suburban enclaves beyond city boundaries. From the last decade of the nineteenth century through the first three decades of the twentieth century, commissions for private home grounds steadily increased so that, for the 1910-1930 decades alone, they numbered more than 1,000 projects.

For Frederick Law Olmsted, the concern was to create tasteful domestic settings, artistically coherent, appropriate in scale and unblemished by extravagant materialistic displays. He sought to enhance natural site features to create a series of separate spaces, giving the home its distinctive character, much as he did in his own domestic landscape at Fairsted in Brookline, Massachusetts, making the two acres seem more expansive. These same design criteria influenced planning for larger estate properties, though for these he often included a greater utilitarian purpose, such as forestry (J. C. Phillips/Moraine Farm in North Beverly, Massachusetts), scientific farming (W. S. Webb/Shelburne Farms in Shelburne, Vermont, which is listed in Burlington, Vermont) or horticultural education with forestry at a uniquely monumental scale of thousands of acres (G. W. Vanderbilt/Biltmore in Asheville, North Carolina).

While essentially retaining these criteria in their residential work, the Olmsted Brothers firm was frequently called upon to include more decorative and formal elements—pergolas, pools, tea houses, etc. —in their estate practice, which flourished in the post World War I years. The client list reads like the Who’s Who of American society, national civic and business leaders as well as prominent individuals from cities across the country. The nexus of grand estates on Long Island for many of these wealthy clients (e.g., Otto Kahn in Cold Spring Harbor, New York; William R. Coe’s Planting Fields in Oyster Bay, New York; and J. E. Aldred in Glen Cove, New York) reflected similar work, some begun by the earlier firm, for clients in Newport, Rhode Island, (e.g., estates for Ogden Goelet, Arthur Curtiss James and John Nicholas Brown, as well as F. W. Vanderbilt’s Rough Point). The firm designed domestic landscapes for multiple generations within families (e.g., Anson P. Stokes in Newport, Rhode Island, and I. N. Phelps Stokes in Greenwich, Connecticut). The firm designed grounds for clients’ city homes and for their country places (e.g., Misses Norton in Louisville, Kentucky, and Hendersonville, North Carolina).

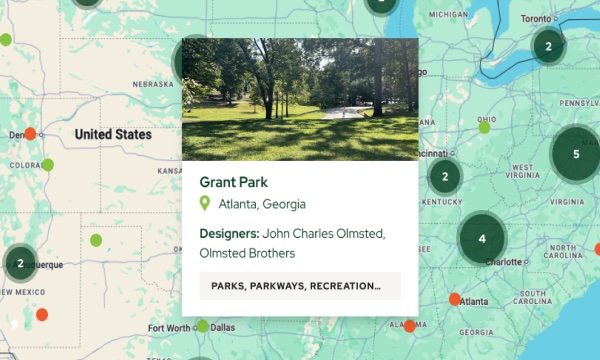

The firm’s extensive planning for residential subdivisions and resort communities across the country led to numerous private commissions within these enclaves. In Seattle, work for The Highlands/Seattle Golf & Country Club generated eleven other residential commissions within this gated community; for the Palos Verdes Syndicate in California the firm worked on nineteen individual projects; for Yeamans Hall in Charleston, South Carolina, on another seven homes while for the Mountain Lake Corporation in Mountain Lake (Lake Wales), Florida, the client roster grew to more than eighty individual listings.

As the economy changed, the Olmsted Brothers firm was called back by several of these substantial clients to plan for subdividing what had once been grand estates. In particular, the original work done in the first decade of the twentieth century for the reconstructed Tudor mansion for I. N. Phelps Stokes in Greenwich, Connecticut, became a multiplot high-end residential community, Khakum Woods. This subdivision, begun in the 1920s, was carefully crafted to retain the original landscape character. Likewise, Fernwood, the original Brookline, Massachusetts, estate for Alfred Douglas, was divided into smaller units. In both of these examples the documents for both the single property and the subdivision are found under the same job number.

However, the Olmsted firm also designed residential grounds on small lots for worker housing within Subdivisions and Suburban Communities, as in the multiple projects for National Cash Register in Dayton, Ohio, or for the Beacon Falls Rubber Shoe Company in Beacon Falls, Connecticut, among other such commercial projects. This residential work is incorporated within the documents under the job number for the larger project. Therefore, as extensive as this thematic category is, there is still more related research to be done to extract the full range of the Olmsted firm’s domestic work from the archival records.