(Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length.)

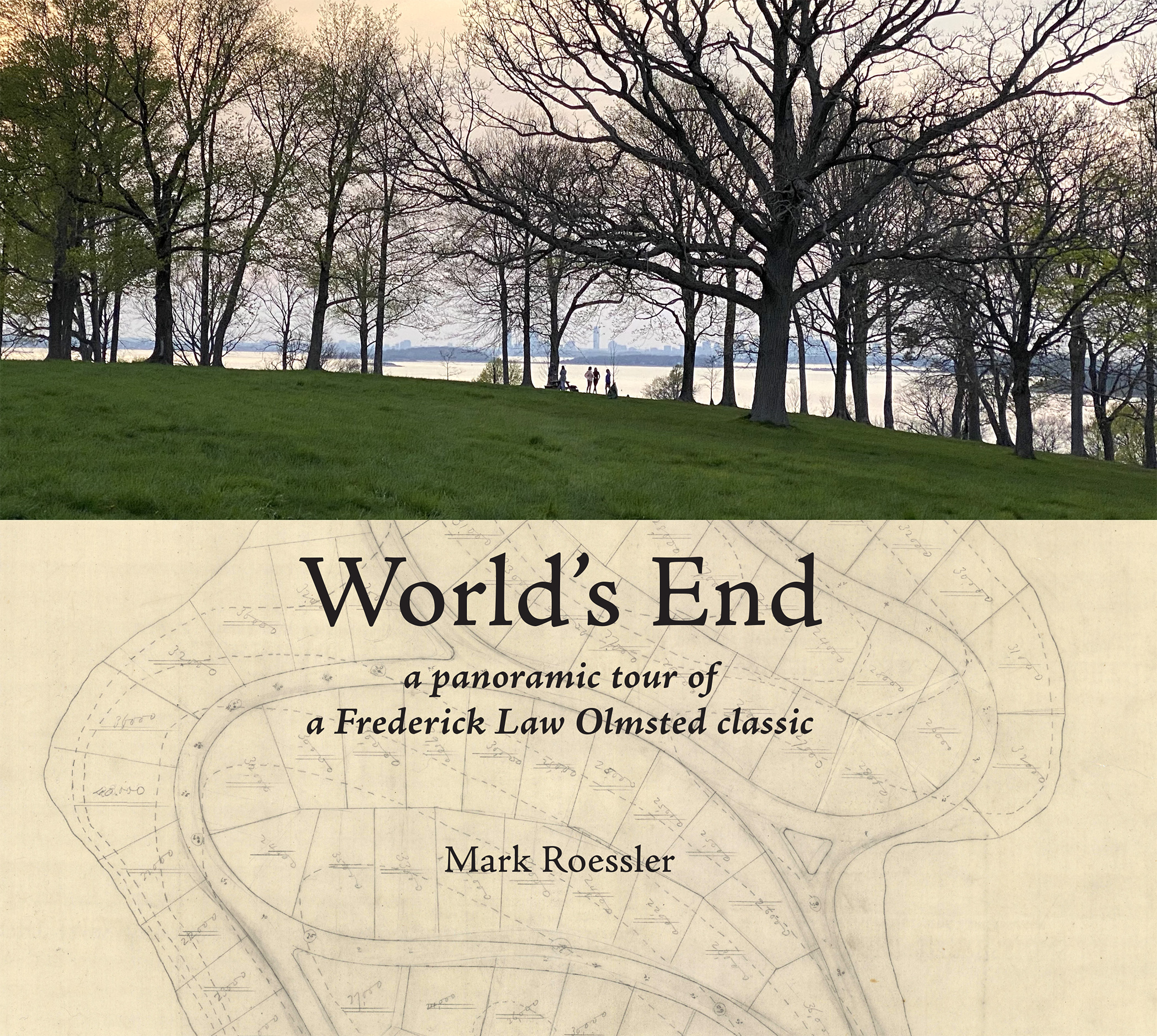

What drew you to write about World’s End?

I’ve been interested in Frederick Law Olmsted since I was a kid. My dad was a preservation architect in New York City during the 1980s and ’90s, and one of his jobs was helping to restore Central Park. Since then, I’ve always been curious about how Olmsted’s works have transformed over time. I enjoy asking and discovering: What’s original to the parks I visit today? What has developed as he imagined, and what’s an addition that conflicts with his original vision?

World’s End is unique in that much of the planned development for the site never happened. What is left is a carefully maintained Olmsted original. Somehow World’s End avoided a series of unfortunate fates.

Olmsted usually collaborated with architects to realize a client’s goals, but at World’s End, his firm worked independently. “Olmsted Unplugged” is the title of the essay that opens my book, and I liken the property to a rock musician’s acoustic album. To me, it was a wonder such a place existed where you could see so clearly the artist playing solo. I wanted to learn how it came to be and share my findings and the place with the world.

I’ve been photographing panoramic tours for much of my professional life. Increasingly, I’ve become focused on historic preservation and documenting spaces that are important and interesting to me. In the past couple of years, I’ve published two collections of my images as books. One volume was of a tour of a demolished state hospital, and the other was a visual document of my college’s final year. For my next book, I wanted to capture a thriving, vibrant Olmsted space. When I first found World’s End on a wet, cold October day in 2019, I knew I’d found the perfect subject.

What are World’s End’s distinctive features?

The most distinctive feature of the property is that there is nothing built on it. Only wildlife lives there. For nearly a century and a half, the stunning landscape has defied commercial development.

Stuck out in the middle of Boston Harbor on two linked islands near Hingham and Hull, Massachusetts, all you see across the water on the coastline that surrounds is development. Houses, factories, marinas, and more houses—everywhere you look. Airplanes from nearby Logan fly a little too closely overhead. But there are no cars, signage, or construction up close, just trees and grass. Only an occasional, well-placed bench interrupts the wilderness.

My book divides the property into three parts, offering maps and original drawings from the Olmsted archives as a way to navigate my panoramas:

1. Planter’s Hill is the highest point on the island, closest to the shore, and accessible via footbridges.

2. Rocky Neck is the lower, undeveloped part of the property that was never realized as Olmsted planned for it. Covered in scruffy pines and meandering paths, the craggy shoreline walk reminds me of Maine.

3. “World’s End” is the name given to the whole property, but it’s also what the second island is called. Further out in the bay, World’s End is linked with a land bridge built long, long ago. There are two smaller hills here with a shady valley running between them. Before Olmsted, all the grassy hilltops were treeless. There were only three big trees on the property. Olmsted’s designs added a balanced mix of open fields and forest. Wherever one looks, there are sweeping ocean vistas and shady wooded glens.

Olmsted was engaged in designing World’s End as a 163-home residential subdivision — how did that assignment inform/affect his plan for the space?

That was a key question that guided my research. Though used as a park now, the Olmsted firm was hired to make World’s End a private enclave filled with mansions. The carriage paths were to be lined by fences behind which would be mown lawns leading to front porches, all fighting for a water view. This was farmland the owner wanted to sell off in as many private housing lots as possible.

With the digitized archives made available by the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, I was able to see how through three drafts, he and his firm developed their plans. Surveys of the land were provided to Olmsted at the start of the project, and he used these as the basis for his work, adding and modifying the roadways that already existed across the property.

Comparing the drafts, it’s clear that maximizing the number of lots was the chief principle guiding the firm’s design. Early on, it appears Olmsted played with the idea of leaving the valley that bisects World’s End free of houses. Subsequent plans include lots there as well. You can see this all in my book.

The correspondence I read was mostly about orchestrating meeting times. One letter signed by Frederick Law Olmsted, though, is telling. Responding to an apparent request to add another road to the settled plan, he dismissed the idea. The grading would be too expensive, and “such a road cuts three good lots all to pieces.”

The pathways he added appear to me to be about both making more lots available and improving circulation through the property. With the bottleneck of the narrow causeway between Planter’s Hill and World’s End, carriage traffic needed to be able to have options when it got to either side.

Unlike Olmsted’s urban parks, World’s End didn’t require any great earthworks or massive reconfiguring of the landscape to achieve a particular effect. No swamps were dredged for ponds or meadows leveled for parade grounds. His client wanted his existing farmhands to realize the plans Olmsted provided. They could grade new roads and plant new trees, so for this job, that’s what the landscape architect had to work with. At a later date, someone else would worry about plumbing and zoning laws for the proposed homes.

Even if it wasn’t meant to be a park, though, World’s End shares many of the qualities of Olmsted’s finest.

It lacks a single sweeping meadow, but it has many smaller ones. There’s no centerpiece plaza or pavilion, but the hills all have their own commanding sense of center. No water features were built—no boat pond or bubbling waterfall—but everywhere you look are sweeping shorelines.

What happened to that plan — why didn’t it come to pass?

The short answer is that John Brewer, the man who hired Olmsted and had his farmhands carry out the work, died in 1893 as the plantings neared completion. His family, it appears, didn’t care how many potential housing lots the property had; they meant to farm it. After his passing, the family farm prospered and grew. Since Olmsted’s path system provided excellent access to all parts of the farm and the trees offered much welcome shade, the farmers not only kept them, but maintained them for years.

During the Great Depression, World’s End stopped being an active farm, but the family continued to maintain the property, allowing locals to wander it at will. Until the 1960s, ideas for development came and went. In the meantime, South Shore residents began to see the property as integral to their quality of life.

The main reason I think the property survives and didn’t become a private enterprise is it’s stunningly gorgeous. World’s End is an enchanted destination full of idyllic spaces. You feel better for having visited. That’s certainly true of many places that aren’t as fortunate as World’s End, but without any steeple in view, it’s almost church-like. You want it to be just the same when you have a chance to return; the idea it might be anything else seems blasphemous.

Other uses have been proposed for the site over the years — what nearly went there, and how was it saved?

Beyond John Brewer’s housing development, the two chief proposals I’ve read about have been a site for a nuclear power plant and a possible location for the United Nations. Given how incredible and isolated the place is, I understand why developers would consider it. As a power plant, the valley between the two hills on World’s End was going to act as a channel for the cooling water. I don’t know what the plan for a U.N. building would have been, but I bet the site’s lack of easy access doomed it. It’s not a direct drive around Boston Harbor from Logan to Hingham.

My guess is that those were just the biggest plans we know about, but there must have been many others. I bet that Brewer’s descendants were pestered by developers and realtors regularly for decades. When they finally put World’s End up for sale in 1967, the family said their preference was for it to be preserved and kept open for public use, but they also needed to be fairly compensated for the prize property. A time limit of a few months was placed on proposals.

That year, the newly formed Trustees of Reservations, and a team of local activists, chiefly based in Hingham, brokered an ambitious deal with the family. The Trustees provided a third of the funds immediately, the local organizers would raise the other third by the deadline on proposals, and the remaining amount could be raised later. The fundraising efforts were epic, but the surge of support for preserving the property met the need.

It was saved by those who treasured World’s End the most—the public who live around it and have made it their own.

Your book features original Olmsted notes, correspondence, and maps — what surprised you as you delved into World’s End’s design history?

The first thing that surprised me is how much original source material about Olmsted is readily available, particularly for projects he undertook while living and working at Fairsted in Brookline, Massachusetts. As someone who’s done research much of my professional life, it’s a rare thing to have so many answers available for the asking.

I have most volumes of “The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted,” edited by Charles E. Beveridge (and an army of others), and I treasure it as my key Olmsted resource. The more I looked into what was available in the archives—letters, drawings, sketches, newspaper clippings—the more I was astonished by the mountain those editors had to cull through in creating their exceptional series. Olmsted and his firm left a vast paper trail that I think will take a very long time for scholars to digest.

The thing I enjoyed the most about researching this book was seeing the hand-rendered and often erased early sketches of the Olmsted firm plans. I’ve always admired the architectural drawings Olmsted and Vaux provided for their work. Everything is perfect, from the renderings of the individual trees to the lettering of the captions. Getting a sense of how that perfection was achieved was rewarding.

I enjoyed seeing that no curve in a path or connection of two routes was taken for granted. Each was carefully honed and reimagined a dozen times before a final solution was found. I’m not certain who in the firm is making those pencil marks, but I know it’s Olmsted’s tutelage and experience guiding the work.

What was Olmsted’s vision for the role parks and shared green spaces should play in society?

When Olmsted and Vaux teamed together to begin work on Central Park, America was still a very young nation, not even a century old. For many here and abroad, the jury was still out on whether democracy was a viable or even desirable form of government. Whatever your opinion, it was impossible to deny the system was fragile and under multiple threats.

Our ancestors faced the same challenges we do today. Race- and class divisions threatened to cause irreconcilable rifts. Economic growth was threatening the environment and making people sick. A few Americans were fantastically wealthy, while many more were in poverty. Although everyone was patriotic, there was little agreement or understanding what being a member of a public of equals meant.

Public parks and shared greenspaces were Olmsted’s radical mastermind solution to all of these problems. He never thought parks would be a complete cure, but he knew they would help. He continues to be proven right.

Though he didn’t invent the concept, we have Olmsted to thank for making public parks a critical component of any American city or town. As he argued throughout his life, no matter one’s status, all human beings require access to natural settings for physical and mental well-being. Rural air was more healthy than city air. Even then, this was not a contentious point.

Olmsted’s radical notion was that a single, magnificently designed, and well-maintained space could not only be shared by all classes, races, nationalities, ages and sexes, but the act of doing so would make everyone involved a more evolved public citizen. Putting a carriage lane next to a common wooded footpath for many people spelled serious trouble. Wasn’t this just inviting banditry? Wouldn’t the rivalries between different immigrant nationalities be played out on a common lawn or promenade? Even Olmsted wasn’t sure his scheme would succeed, but his long career is a testament to how well it did.

Today, these spaces are so ubiquitous and central to so many lives, and we tend to take public parks for granted. To Olmsted, though, the quality and vibrance of our public parks was like a canary in a democratic coal mine. If you let your public spaces deteriorate, what’s next? I think that’s a useful gauge for us still.

What is Olmsted’s importance in 21st century America?

I think it’s impossible to overstate Olmsted’s importance today.

As I said previously, he faced the same kinds of challenges the world faces today—race conflict, environmental disasters, and civil unrest—and with public parks and introducing greenspace to urban centers, and he provided long-term solutions that continue to work. His ideas were so effective, and they are now part of the framework of what it means to be an American city. What’s a city without a park?

And it wasn’t just his work as a landscape architect that was transformative.

To understand slavery, he traveled the South. He documented what he saw as a journalist, providing an invaluable firsthand account published in newspapers of the day that influenced many readers. When the Civil War broke out, he left work on Central Park to serve the Union Army, becoming a leader in the Sanitary Commission. His efforts organizing donations on a national scale and coming up with better procedures for attending to the wounded on the battlefield contributed to the forming of the Red Cross and how American ambulances still prioritize their work during an emergency.

Before he returned to park design, Olmsted spent several years managing a mine in the West. Though the mine went bust, he understood the importance of the wild scenery of places like Yosemite or Niagara Falls long before others did. His was one of the first voices proclaiming the need to protect them.

So many of America’s greatest places owe a debt of gratitude to Frederick Law Olmsted, and it might be easy to think we’ve squeezed him dry of new inspiration. Studying his parks and his writings about working together for the common good, though, I think his ideas and achievements still offer guidance on how to meet today’s challenges. He often writes about what it means to serve the public while also being a member of the public. It was a concept that was new then and not well understood now.

Some general themes I often see repeated in his written work and his parks that inspire me every day:

In addition to averting ecological disaster, the planning we do now about how we shape our environment can make our world more beautiful, livable, and equitable than it was before.

Small things we do now will have lasting repercussions for generations.

And while fences might make for better neighbors, a democratic country that values the common good needs to prioritize the creation, upkeep, and use of public spaces and services. Being a citizen of a democratic nation has daily responsibilities that go beyond occasionally voting. Acknowledge one another while passing on the sidewalk. Occasionally jump up from what you’re doing to return a stranger’s ball. When you can, take a walk in a park, sniff what your neighbors are grilling for dinner and enjoy overhearing their music. Wave hello. Repeat often.

What makes World’s End unique among Olmsted-designed spaces?

I believe World’s End is unique in being the only Olmsted landscape surrounded on all sides by salt water. There are other coastal Olmsted parks, such as in Bridgeport, Connecticut, but none with such an intimate relationship to the sea. So close to the Atlantic Ocean, the property’s coastline fluctuates with the tide.

Historically, I think it’s also significant that Olmsted was first contacted about the project just weeks after his close friend and colleague, the architect H. H. Richardson, died of a sudden heart attack. Unlike other properties Olmsted worked on, World’s End was not a collaboration with another architect providing bridges, stairs, and buildings. Construction was supposed to follow later. But in its absence, World’s End is a demonstration of Olmsted’s basic design principles, undiluted by anyone else’s influence. It’s a pleasure to see how his work stands happily on its own.

Do you have a favorite spot in World’s End, and what is your favorite season in which to visit?

I’m still searching for my favorite spot.

I especially like the most northern carriage way, wrapping around the furthest part of the furthest island. The grassy lane running through the row of trees is so stately, but the human touch appears to be so very light. It’s one of many church-like spaces there: ideal for personal contemplation or deep, one-on-one discussions. But the Valley on either end of that loop is also always a welcome transition that makes me whisper when I’m there.

My book includes panoramic images taken during all seasons. Summer is lush, and the breezes from the sea are most welcome. Winter is stark, but the sea views are widest then and most stunning. The paths are left covered in snow during the winter. People clearly enjoy snowshoeing and skiing but walking there in winter I’ve found to be hazardous. Autumn, as it is all over New England, is probably the most stunning, but I’m always a fan of the Northeast in May.

You can order your copy of World’s End: a panoramic tour of a Frederick Law Olmsted classic here!