Riverside Park Conservancy recently launched its “More Trees, Less Trash” campaign in an effort to both protect and beautify the historic Riverside Park in New York City.

Staying true to the design history of this iconic Olmsted park is, of course, a complicated undertaking. The New York City Parks Department (NYC Parks) is the guardian of the park’s history and protector of the city’s urban forest, while the 40-year-old non-profit Riverside Park Conservancy has raised tens of millions of dollars for the park and provides both capital and operational support, including 24 full-time gardeners.

Margaret Bracken, NYC Parks’ landscape architect for Riverside Park, and John Herrold, the Riverside Park administrator, kindly responded to these questions about how the initiative to plant new trees was approached.

Why was the campaign needed?

It might be easily overlooked amid the day-to-day of park maintenance, but sustaining the urban forest is a continuous proposition. Natural forces of age, weather and pathologies take their toll, as do human impacts such as wayward vehicles, road salt, construction and even vandalism. Public safety and tree health require regular pruning and inspection. NYC Parks’ Forestry Division, in partnership with the Natural Areas Conservancy, focuses on these critical efforts throughout this city of five million trees.

Within the NYC Parks system, Riverside Park is fortunate to have dedicated personnel with expertise both in design and on-the-ground tree care, and its public resources are augmented through the public-private partnership with Riverside Park Conservancy, which holds a maintenance and operations agreement with the cIty.

The “More Trees, Less Trash” initiative resulted from Riverside Park Conservancy recognizing that the community cares deeply about trees and their critical role in city life and even urban survival. Whether it is as simple as making sure every sidewalk tree bed is filled or protecting an allée of priceless American elms from Dutch Elm Disease, people are eager to see that their contributions can have a direct impact on trees in the park. Indeed, more than 500 donors contributed to the campaign. With this funding, NYC Parks was able to plant 54 street trees at various locations along Riverside Drive.

How did you select the new plantings? Did you reference the original planting plans?

Yes, but that is not the simple question it may seem.

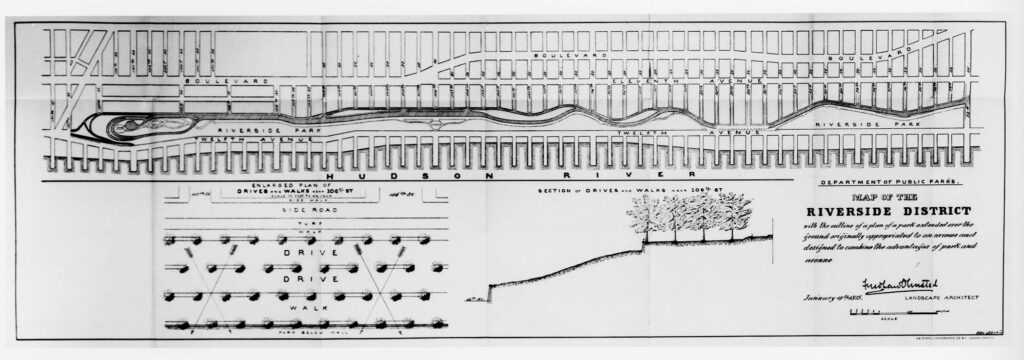

Riverside Drive and Park, from West 72nd Street to St. Clair Place, were Frederick Law Olmsted’s vision. The naturalistic curves of Riverside Drive and massive bedrock retaining wall which follow the curves and undulation of the natural topography of the site speak to Olmsted’s attention to preserving and enhancing the natural advantages of any site. While the defining characteristics of the park are pure Olmsted, the execution and the subsequent life of the park over the past 150 years represent multiple design layers.

Olmsted’s concept was executed by Calvert Vaux, Samuel Parsons and others in the 1870s. In the early 1900s, the Department of Public Works’ construction of the 125th Street viaduct, as designed by F. Stuart Williamson, allowed for the northward expansion of Riverside Drive and the slender strip of parkland located between Riverside Drive and the railway tracks of the New York Central Railroad. This expansion of the park to 153rd Street displays a very different design aesthetic from the more naturalistic Olmsted design to the south. This northward expansion adheres to the more formal Beaux Arts aesthetic of early 1900s New York City. Where the Olmsted design made ample use of the original Manhattan mica schist bedrock of the region, the later retaining walls and stair ensembles to the north use stone quarried in Maine.

In the 1930s, under Robert Moses, architect Clinton Loyd and landscape architects Gilmore Clarke and Michael Rapuano designed the Park’s westward expansion, creating much of the present topography, added acreage and 20th Century park features we see today. Athletic fields, playgrounds, field houses and public restrooms, parking lots and a marina are among the park elements never imagined by Olmsted— who designed a park for strolling, passive recreation and enjoyment of river views— but are central to how the public experiences and enjoys the park today. With the park now triple the size of Olmsted’s, there were new pathways, promenades with allées of London plane trees— a Moses favorite— and newly planted woodland slopes.

Most of the mature trees we see in the park today, including the elms and lindens along Riverside Drive, were planted in the 1930s, often replacing many of the sixty-plus year-old trees specified by Olmsted in the original park construction. The Olmstedian park was completed over a period of 20 years from around 1879 to the early 1900’s, whereas the Robert Moses era park expansion was built over a period of just two years. The horticultural palette of the Moses era is limited in terms of tree species, so where appropriate, we have expanded the palette to increase diversity. We do have the planting plans from the 1930’s. They are an interesting and helpful tool in our park restoration work, but the plans include many species that NYC Parks no longer plants, Norway Maple being one example.

Beyond adhering to original plans or adapting them to current park use, other considerations of modern arboriculture include varietal choices for disease resistance, structural strength for greater public safety and tolerance of extreme weather. There is also a transition away from monocultures except when intentionally preserving a historic grove or allée.

The choice to not plant can also represent adherence to original design, where, for instance, an important sight line is to be preserved or in some cases restored following the loss of later plantings that blocked those intended views. It is well documented that Frederick Law Olmsted felt that the park had been overplanted as his original design intent was to retain clear views of the Hudson River. No Olmsted park is complete without a significant water feature, and in the Hudson River, he felt there were views well worth preserving. It is notable that in his schematic layout for Riverside Drive, dated 1875, Olmsted appears to have consciously staggered the tree layout to create oblique views of the river. It seems even the choice of trees reflected this intent. We do not have the planting plans for the Olmsted design, so we rely on archival photographs to provide some indication of the species, which appear to be mostly oaks with an unusual number of fastigiate trees, presumably to assist in retaining the views.

The trees planted this fall through Riverside Park Conservancy’s “More Trees, Less Trash” initiative are all in-kind replacements for trees lost on Riverside Drive. Although other species were planted at various times over many years, we have chosen to retain the distinctive, arching canopy of both American Elms, replaced with DED resistant cultivars and Little Leaf Lindens, with their similar canopy structure, delicate flowers and stunning fragrance. These are distinctive features, recognized and preserved by Moses’s designers, which define the historic Olmstedian aesthetic of Riverside Drive.

How will this help with climate change?

Trees are an important counterforce to both the effects and the causes of climate change.

Trees cool the air passing around them by releasing water vapor. The shade they cast keeps sun off whatever is below them— whether a sidewalk, a home, a parked car or a playground, keeping them cooler. In addition to casting shade below, trees and other vegetation stay cool themselves by reflecting more sunlight than pavement, roofs and other manmade materials. Most city dwellers have experienced the noticeable drop in air temperature when crossing the street away from concrete buildings— which hold heat for hours after the sun sets— and toward a leafy park. They have felt the difference in temperature between a tree-lined block and one without trees.

These cooling effects can also slow climate change itself by reducing the demand for air conditioning and the power it requires. The breeze through a window will be hot coming directly off a hot street but cooler if the air has been shaded and cooled by street trees or the trees in a nearby park. A house or office building shaded by trees will not get as hot as one fully exposed to the sun. In winter, a house or office building protected by a windbreak of trees will lose less heat and require less energy to keep warm.

Of special importance is the ability of trees to trap some of the very “greenhouse” gasses causing climate change. Trees and other vegetation pull tons of carbon dioxide out of the air and store it, keeping it out of the atmosphere.

New York City’s five million trees— including 600,000 street trees— have a critical impact in all these ways. The financial support of Riverside Park Conservancy and its donors is essential to our collective effort to protect the trees lining Riverside Drive and the overall canopy of Riverside Park.

Margaret Bracken serves as NYC Parks’ landscape architect for Riverside Park and Riverside Park Conservancy’s chief of design. Between her current work at Riverside Park and previous work at Prospect Park in Brooklyn, Bracken has more than 25 years’ experience overseeing design and construction in Olmsted parks, ensuring that design history is honored and protected while creating park spaces for the 21st Century.

John Herrold has had various roles at Riverside Park over the past 35 years and has been in his current position as NYC Parks’ park administrator since 2006. Herrold is a former president of the Riverside Park Conservancy and now serves as a senior advisor and an ex officio board member.