The Olmsted firm has long been recognized as one of the foremost creative forces that shaped the distinctly American typology of the college campus. F. L. Olmsted and his sons and partners worked with over 150 schools, applying their multidisciplinary skill set and collaborative practices to envision and realize comprehensive plans for campuses in some of the same ways as they did for parks or suburban communities. While they had the opportunity to design some campuses out of whole cloth, at many other schools their work comprised more piecemeal consulting. In 1905, John Charles Olmsted wrote to his colleague George A. Parker, Superintendent of Keney Park, Hartford, CT, about the Olmsted firm’s work at Vassar College, where JCO had consulted about ten years earlier:

It is almost impossible to make a definite plan for the continued development of such a college, which already has many buildings, and, presumably, insufficient land for a comprehensive plan. Of course we are able to do our best work in advising colleges when we are in at the start, as was the case with Leland Stanford Jr. University, Washington University, St. Louis, American University at Washington, Lawrenceville School at Lawrenceville, N. J., the Groton School and a few others. Up to the present time, we have given advice of some sort, usually merely preliminary reports for over sixty universities, colleges and endowed schools. I think these colleges ought to consult us whenever any new buildings or other similarly important change in existing conditions is contemplated, but, while some college professors seem to grasp this idea, they usually, I suppose, are unable to secure the approval of the trustees to the necessary expenditure.

While the bicentennial of Frederick Law Olmsted’s birth has prompted many colleges and universities to dig into their histories as “Olmsted campuses”, research often reveals complex narratives that open interesting questions about what phase of campus design, which Olmsted, and how their recommendations were implemented. This situation in part reflects the iterative nature of campus planning, with an ever-changing cast of campus agents. How can we factor such checkered planning histories into the Olmsted legacy as a shaper of educational institutions?

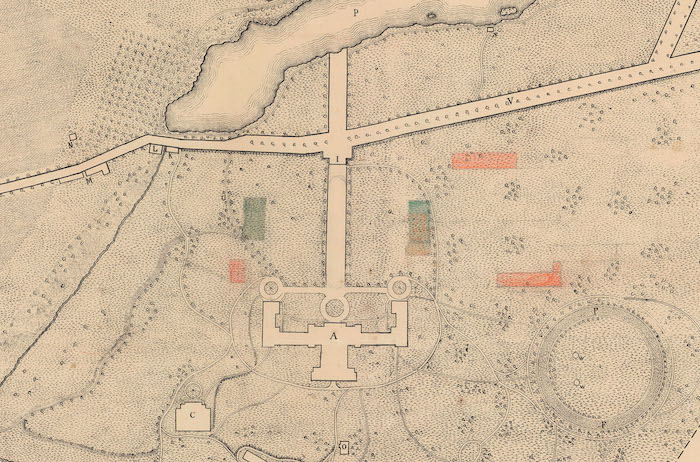

The Olmsted firm’s interventions at Vassar College provide an interesting case study. New research in the Library of Congress, the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, and Vassar Special Collections has uncovered a trove of unstudied drawings, documents, and photos. It emerges that three generations of the Olmsted firm consulted at Vassar, at different stages. When the college opened in 1865—the first to give women the same education as men—it was housed in a single, monumental building, sited in an expansive rural landscape in the Hudson Valley. Just three years later, the trustees turned to Frederick Law Olmsted, who, together with his partner Calvert Vaux, visited the campus in August, 1868. They produced an outline sketch for improvements to roads and paths, as the trustees recorded. However, no trace of this drawing has survived, despite searches from 1896 to the present, and there is no evidence that any campus changes were undertaken as a result of it. Most likely, early accounts of the pair’s visit were exaggerated, and their involvement became legend.

Near the turn of the century, when the college had outgrown Main building, Vassar once again turned to the Olmsted firm. Olmsted Senior had just retired from practice, and so John Charles Olmsted visited the campus in July, 1896. Drawing on the “principles and rules governing convenience and design” championed by his father, JCO recommended the allocation of land in the central campus for a growing nucleus of what he called working buildings (recitation rooms, assembly halls, laboratories), with a peripheral zone designated for residential buildings. He proposed that a large central quadrangle be formed by placing buildings on either side of the axial entrance drive leading to Main Building—which is exactly what the college did. Although the Olmsted firm is often said to have favored natural, park-like campus designs, they often recommended a central quadrangular space as a focal point for social and academic exchange; especially at this moment, following the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, their campus designs were typically characterized by formality and symmetry. The relative merits of the formal or winding, picturesque modes had been a recurring issue in Vassar’s history. So JCO’s recommendation for a rectangular greensward (along with some advice on the siting of dormitories) established the formal, quadrangular core of the Vassar campus, which has been preserved down to the present.

Vassar turned to the Olmsted firm once more three decades later. By the late 1920s, with the expanded campus footprint mostly established—in part along the lines that JCO had recommended—and the widespread adoption of the automobile, attention shifted from siting and constructing buildings to circulation and landscaping. JCO had died in 1920, so Vassar contacted Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., who instead suggested his partner Percival Gallagher, whose campus experience included Duke, Harvard Business School, and Bryn Mawr. For Vassar, Gallagher directed a highly detailed topographical study, advised on grading, walkways, and roads, and proposed plantings for new areas of campus. He collaborated with the campus groundskeeper (Kew-trained horticulturist Henry E. Downer) and the Chair and Professor of Botany Edith A. Roberts, the pioneering eco-botanist who had created the Dutchess County Ecological Laboratory of species native to the county, grouped by associations. Gallagher deftly resolved tensions between these two figures, involving debates over the privileging of native or exotic species.

But Vassar has rarely worked with one design consultant for long; the college has invited the direction of a distinguished roster of landscape architects over time, including Loring Underwood, Samuel Parsons, Jr., Beatrix Farrand, Eero Saarinen, Hideo Sasaki, Michael Van Valkenburgh, and Gary Hilderbrand. All have added new layers to the campus; buildings have been inserted, circulation revised, and plantings replaced, recasting connections among buildings and sectors. Yet the central core of campus envisioned by J. C. Olmsted remains virtually unchanged, its simple and clearly-defined form and functions reflecting the Olmstedian principles of convenience and design he so forcefully espoused over a century ago. The college also owes details of circulation and plantings to the thoughtful proposals of Percival Gallagher. Additionally, beyond their legacy in the campus itself, the Olmsteds’ writings and drawings further raise fascinating questions about gendered design for a women’s college, and the changing role of the landscape architect in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Yvonne Elet is Associate Professor of Art History at Vassar College. Her teaching and publications focus on intermedial designs for art, architecture, landscape, and urbanism in early modern Italy, and in the twentieth century. She created the website Vassar Campus History, a digital repository for ongoing research on the history of the college’s architecture, landscape, and soundscape. Together with Caleb P. Mitchell (Vassar ’22), she curated the exhibition The Campus Green: The Olmsted Firm’s Designs for Vassar College, on view in the Vassar College Art Library, Poughkeepsie, New York, from April 11 through June 6, 2022.

Further Reading:

Yvonne Elet, “Échelon, Quincunx, Quadrangle: The Olmsted Firm and Campus Planning in the Early Decades of Vassar College,” Journal of Planning History (March, 2022).

Yvonne Elet and Caleb P. Mitchell, The Campus Green: The Olmsted Firm’s Designs for Vassar College, exhibition brochure, Vassar Art Library, April 11-June 6, 2022.

Yvonne Elet and Virginia Duncan (VC ’16), “Beatrix Farrand and Campus Landscape at Vassar: Pedagogy and Practice, 1925-29,” Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes 39 (2019): 105-136.

Karen Van Lengen, “Pedagogy and Place. The Legacy of the Landscape at Vassar College,” in Landscape and the Academy, ed. John Beardsley (Harvard University Press/Dumbarton Oaks: 2019), 147-75.

Karen Van Lengen and Lisa Reilly, Vassar College: An Architectural Tour (The Campus Guide) (Princeton Architectural Press, 2004).