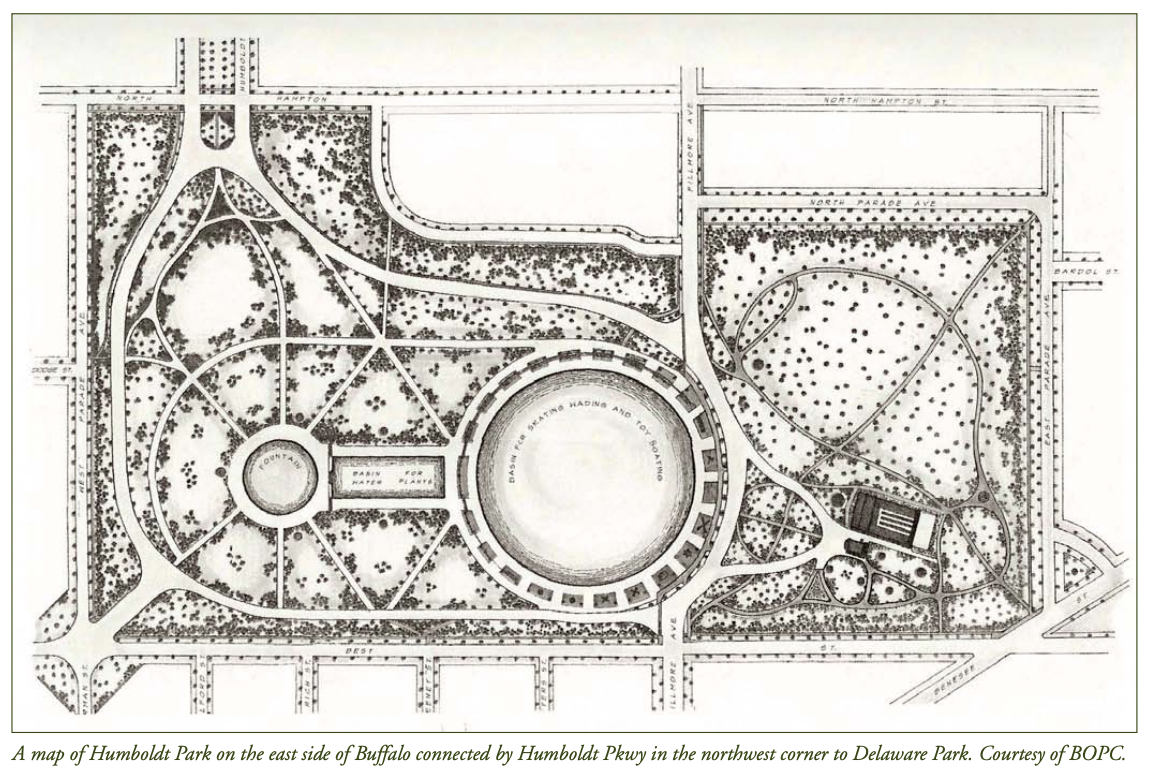

The Olmsted firm originated in the Fall of 1857, when Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux agreed to enter the design competition for Central Park in New York. When their “Greensward” plan was awarded first prize in April 1858, the two men undertook to supervise construction of the park—Olmsted as Architect-in-Chief and Vaux in a subordinate position as Consulting Architect. During the next seven years they collaborated on a few commissions—a cemetery in Middletown, New York, the Hartford Retreat in Connecticut, Bloomingdale Asylum in New York City, a street system for the Fort Washington section of Manhattan and a few private estates, but apparently had no formal partnership arrangement. This situation changed in the fall of 1865, when they formed the firm of Olmsted, Vaux & Co. The partners secured a number of important commissions, including parks and parkways in Brooklyn, a park system in Buffalo, the Chicago South Park and the residential suburb of Riverside, Illinois. Olmsted was also a partner in the architectural firm of Vaux, Withers & Co. Both partnerships dissolved in 1872.

For the next dozen years, Olmsted carried on his practice in New York City with the assistance of English-born architect Thomas Wisedell and several other architects and engineers. He also relied on the skills of Swiss-born landscape gardener Jacob Weidenmann. As early as at least 1874 his stepson John Charles Olmsted assisted him in his work, and during some periods his wife, Mary Perkins Olmsted, served as amanuensis. Major projects in this period included the United States Capitol grounds, the park on Mount Royal in Montreal, the park on Belle Isle in Detroit, the Back Bay Fens in Boston and the street and rapid transit system of the Bronx.

After his dismissal from the New York City parks department in 1878, Olmsted began the transition to the Boston area that resulted in permanent change of residence to Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1882. There, at “Fairsted,” he began to form the firm that continued to operate from Brookline until 1979, when the property, structures and collections became part of the National Park Service as Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

In 1884, John Charles Olmsted became a partner in the firm of F. L. & J. C. Olmsted. In 1889 another protégé whom Olmsted had trained, Henry Sargent Codman, became partner. This period ended abruptly and tragically with Codman’s death in 1893 at the age of twenty-nine. During this period the firm continued planning of the Boston Emerald Necklace and designed other park systems for Louisville, Kentucky, and Rochester, New York. Other significant commissions were the Niagara Reservation, the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, Lawrenceville School, Stanford University and the suburban community of Druid Hills in Atlanta.

Following the death of Henry Codman, Olmsted convinced his former student Charles Eliot to join the firm, renamed Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot. Eliot brought to the firm the planning of the system of metropolitan reservations surrounding Boston, which he had inaugurated during a decade of independent practice. He continued to focus on the parks of the Boston area and played an important role in developing other park systems, notably that of Hartford, Connecticut. Eliot’s career was cut short when in 1897 he died from meningitis at the age of thirty-seven. Thus two of Olmsted’s three highly promising successors, on whom he relied heavily for perpetuation of his design concepts, died prematurely during his own lifetime.

Olmsted had ceased active practice in 1895, a victim of failing memory and vitality. The new firm formed after Eliot’s death had the old title of F. L. & J. C. Olmsted, but the son had replaced the father in it. A year later, in 1898, John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. formed the partnership of Olmsted Brothers, a name the firm would retain until 1961, some forty years after John Charles’s death in 1920 and four years after his half-brother’s death in 1957. In the process, a full century had elapsed during which a man named Frederick Law Olmsted practiced landscape architecture in the firm.

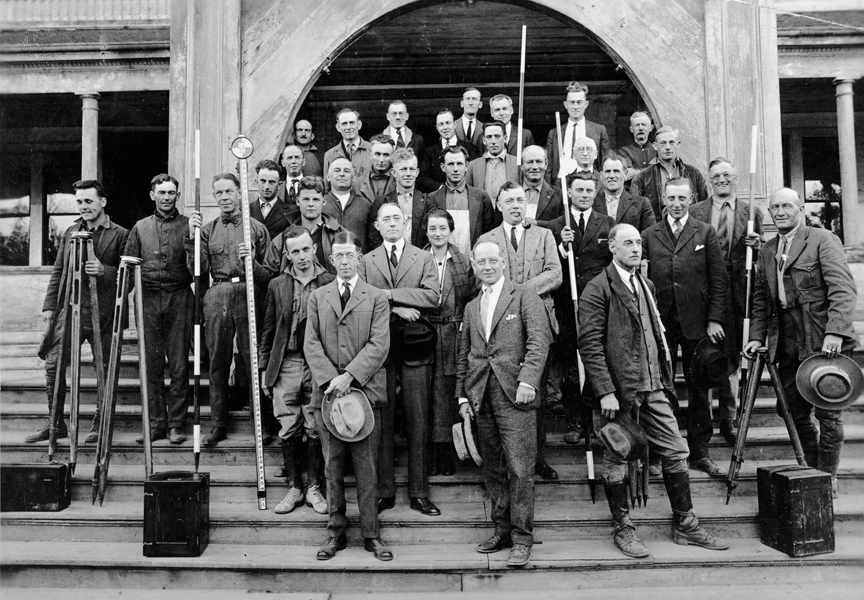

The first three decades of the twentieth century witnessed a great increase in the work of the firm and the size of the staff, which reached forty-seven by 1917 and up to sixty at its height in the 1920s. During the four decades of the elder Olmsted’s practice the firm carried out some 500 commissions, many of those coming in the 1890s. By the onset of the Great Depression of the 1930s, that number had increased to 2,500. The years prior to the First World War were the firm’s most active period, involving the planning of extensive park systems for a dozen metropolitan areas. The 1920s produced little new park work other than expansion of these metropolitan park systems, but the period marked a significant increase in residential subdivisions and suburban communities, including those of Lake Wales in Florida, Palos Verdes in California and Forest Hills in New York. The decade also accounted for fully one quarter of the 2,000 commissions the firm received for the grounds of private residences and estates. One vast project, Fort Tryon Park in Manhattan, proved to be the principal enterprise for the firm during the Depression of the 1930s, supplemented by extensive work for British Pacific Properties, Ltd., in Vancouver, British Columbia. Few commissions followed the Second World War, and the only major project of the firm following the retirement of Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. from active practice in 1949 was the extension of Rock Creek Park from the District of Columbia into Montgomery County in Maryland.

Olmsted taught his design principles to his pupils and partners: John Charles Olmsted, Henry Sargent Codman and Charles Eliot and, less formally, his son and namesake, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. They in turn passed on elements of his teachings to later partners and staff members. The list of these landscape designers is long and includes later partners in the Olmsted firm during the period covered by this Master List of projects: James Frederick Dawson, Percival Gallagher, Edward Clark Whiting, Henry Vincent Hubbard, William Bell Marquis and Leon Henry Zach. It also includes landscape architects who became partners in the firm after the retirement of Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., including Carl Rust Parker, Charles Scott Riley, Artemas Partridge Richardson and Joseph George Hudak. Others about whose design principles and practice the projects in this list will provide new information are members of the firm’s staff who subsequently established their own landscape practices, such as Warren Manning, George Gibbs Jr., Frederick G. Todd, William Lyman Phillips, Emil Mische and Arthur Shurcliff.

Assessing the Work of the Olmsted Firm

During the past three decades, there has been a great increase in public awareness and appreciation of the work of Frederick Law Olmsted and his successors in the Olmsted landscape architecture firm. Beginning with the Olmsted Sesquicentennial of 1972, numerous books and articles, films and exhibitions have appeared on the subject of Olmsted and his design legacy. During these years Olmsted’s home and office in Brookline, Massachusetts, became part of the National Park Service, which has conserved and made available to researchers the large volume of material there. At the same time, the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, has organized and microfilmed the three hundred linear feet of documentary material—reports and correspondence—that constitutes the principal written record of the work of the firm. Drawing from these resources, eight volumes of the projected twelve-volume series of the Frederick Law Olmsted Papers editorial project have been compiled and published. A collaborative undertaking between the National Park Service and the National Association for Olmsted Parks has created the Olmsted Research Guide Online (ORGO) and The Master List of Design Projects of the Olmsted Firm 1857–1979, comprehensive reference tools for materials at Olmsted NHS and the Library of Congress. The National Association for Olmsted Parks, formed in 1980, has been active in publicizing the work of the firm and encouraging the formation of very active Olmsted-related organizations in several states. Many programs for the preservation and rehabilitation of Olmsted parks and landscapes have been created throughout the country and in Canada.

In the process, a renewed awareness has developed of the significance of the role of the Olmsted firm in the history of landscape architecture in the United States—the extent of its legacy, the quality of its designs and the significant influence it has had on millions of people since the mid-nineteenth century. Particularly important to this awareness has been the rehabilitation and restoration of public parks designed by the firm, a movement that began in New York City in the 1980s and has since spread to include parks in most of the major cities for which the firm planned parks and park systems. Included in this list are Boston, Seattle, Louisville, Atlanta, Montreal, Essex County in New Jersey, Denver, Baltimore and Rochester, New York. Those cities, along with numerous others, have rediscovered the past and future value to their citizens of their Olmsted-firm parks. The special genius of the Olmsteds and their firm has proved to be a priceless resource for many communities.

Still, despite the survey and inventory work done in a few states, the extent of the firm’s role in shaping the landscape remains for the most part unexplored. Even the number of designs the firm made and carried out is not known. The general figures we have are impressive: between 1857 and 1979 the firm participated in some way in more than 6,000 projects. The basic records of the firm indicate that it drew at least one plan for more than 4,000 of these, including more than 700 public parks, parkways and recreation areas, more than 2,000 private estates and homesteads, more than 350 subdivisions and suburban communities, more than 250 college and school campuses and the grounds of a variety of buildings—almost 100 residential institutions (hospitals and asylums), 100 libraries and other public buildings, more than 125 commercial and industrial buildings and more than 75 churches. For the vast majority of these projects, research has not been done to determine the role of the Olmsted firm—how extensive the planning by the firm was, how much of the design was carried out, what the present condition is and what additional documentary sources exist to guide the preservation and restoration process.

In addition to clarifying the extent of the work of the Olmsted firm, the research to be done on the basis of this Master List should reveal much new information about the design philosophy and professional practices of the firm. It will supply information concerning the approach of Frederick Law Olmsted, his partners and his successors to a whole range of issues—design concepts, construction practices, provision for long-term growth and maintenance of plantings and relations with practitioners in related fields, among others.

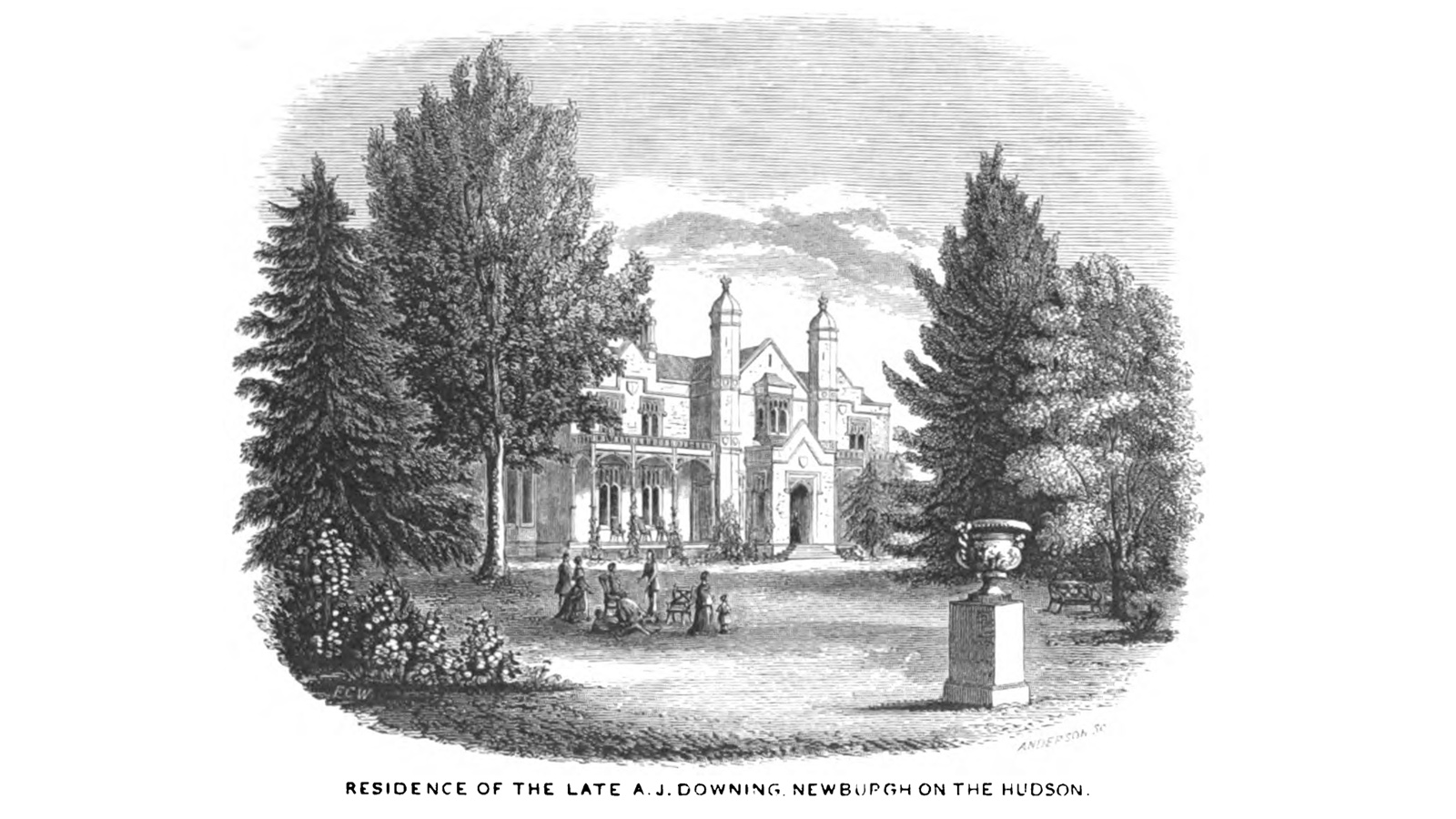

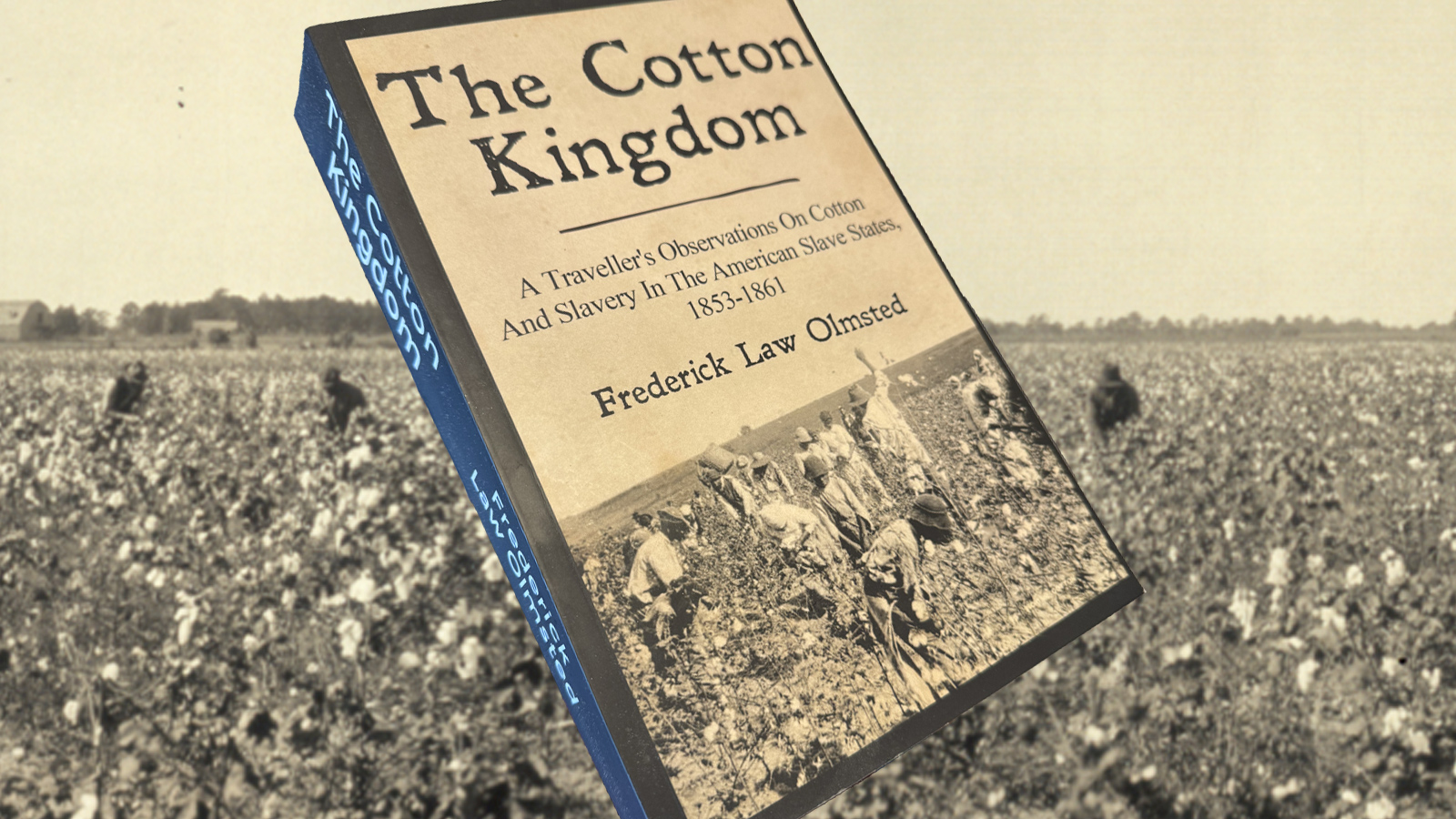

Frederick Law Olmsted himself had an ambitious conception of the role that landscape architecture could play in improving the quality of life of Americans. His extensive travels in the antebellum South, his two-year sojourn in California and his travels in the British Isles, Europe and China provided remarkable breadth of experience, while his career as a writer and publisher helped clarify his views on a whole series of questions concerning art, politics, economics and social organization. By the end of the Civil War, he had defined what he hoped American society would become and had chosen the means by which he would promote those ideals during the next thirty years.

Olmsted had great faith in the ability of his art to improve society and in particular to promote a sense of community in the rapidly growing urban centers of the country. His great parks and park systems were to be spaces held in common by all residents of their cities, places where all classes could mingle, free from the competitiveness and antagonisms of workaday life. His plans for residential suburbs, too, provided common ground that would foster both physical health and what he called “communitiveness”—the impulse to serve the needs of one’s fellow citizens.

In addition, Olmsted believed that scenery could have a powerful, restorative influence. He was convinced that the spacious, gracefully modulated terrain of his parks provided a specific medical antidote to the artificiality, noise and stress of city life. In this and many other ways he strove to use his skill as an artist to meet the most fundamental of human needs in a comprehensive way. The psychological power of scenery, he felt, could be achieved in landscape design only through subordination of all elements to the creation of a single effect. There must be no specimen planting or placing of works of architecture or sculpture to be viewed for their individual beauty. In the same spirit, he excluded ornamental and decorative features from the buildings he designed, preferring a simple, organic plan that concentrated on fulfilling a particular function. “So long as considerations of utility are neglected or overridden by considerations of ornament,” he taught, “there will be no true Art.”

For reasons of function as well as effect, Olmsted carefully separated different activities and different styles of planting. He abhorred an “incongruous mixture of styles,” feeling that each designed space should have a single, coherent character. Likewise, he separated potentially conflicting uses in his parks, creating for each activity a setting carefully designed for it. In his parks and parkways he also separated different kinds of traffic, for reasons of both enjoyment and safety.

How closely Frederick Law Olmsted’s successors adhered to his principles, in the face of changing technology, social conditions and recreational needs, has yet to be determined. The research that stems from the publication of this Master List will provide a far more complete answer to that question than can be offered at the present time. In the process, much will be learned about the significance of the Olmsted firm for the designed landscape of America, and much practical knowledge will be secured for the process of preserving and restoring the designs of Olmsted and his successors.

Notes:

1 Olmsted to Charles Loring Brace, Brookline, March 7, 1882, The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, Volume VII, Parks, Politics, and Patronage 1874–1882, eds. Charles E. Beveridge, Carolyn F. Hoffman and Kenneth Hawkins (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007): 592.