Credit: Gay Legg

Central Park is so iconic, so recognizable, that flying up the Atlantic coast on a clear day, you can spot it from 30,000 feet. In summer, it’s a brilliant green jewel, emerald cut from the gray walls around it, and set with tiny blue sapphire water features—in fall, a blazing yellow topaz in the midst of the concrete, steel, and glass hardscape that is Manhattan. Central Park is the most familiar of New York City’s parks, attracting millions of visitors annually to its famous 843 acres of pastoral landscape and often considered the epitome of American urban parks. Central Park is like the family beauty that overshadows its Cinderella sister located a little farther east in Brooklyn: Prospect Park.

Ah, Prospect Park! Across the bridges (Brooklyn and Manhattan—you thought there was only one?), in that other borough, where the Dodgers used to play ball—now the boho-chic area full of creative types, where rents were, for a brief moment, more affordable than Manhattan. Prospect Park, bypassed by tourists, is the beautiful “secret intelligence” of Brooklyn residents. Served by multiple subway routes and with relatively easy parking, it’s not so hard to explore this beauty.

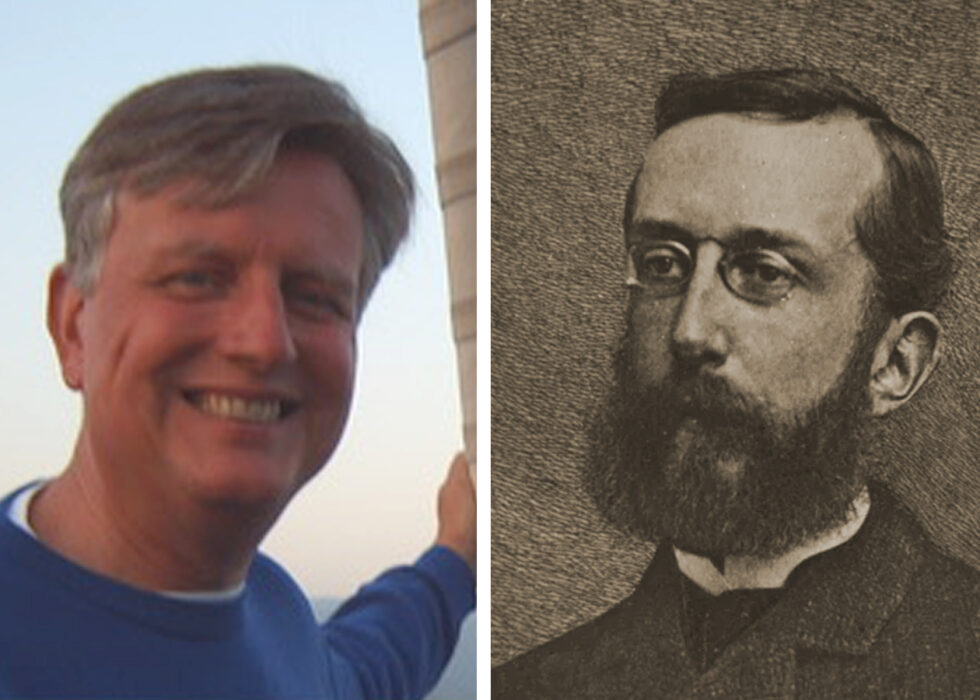

As seen on a map, the two parks look very different. While Central Park has straight edges with squared corners, Prospect Park is rounded—not so neatly edged. It’s the wild backyard of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. Like Central Park, however, which is bordered on the west by the Museum of Natural History and the east by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Prospect Park is also at an aesthetic junction: almost adjacent to the great Brooklyn Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Public Library, with its famous bronze Art Deco gate. But the common parentage of Central Park (1858) and Prospect Park (1866) is the famed team of Frederick Law Olmsted and British architect and landscape designer Calvert Vaux.

What brought them together was a competition, spawned by wealthy New Yorkers back from the Grand Tour, to design a park as magnificent as those they’d seen in Europe. Their winning plan was called Greensward, and implementing it meant overcoming some serious hindrances, the swampy nature of the site (which was why it had been passed over for earlier development) chief among them. Add to this the rock formations rising from it–some of these can still be seen–and two existing water reservoirs to be built around. The result was an expensive project relying on dynamite, lots of imported (from New Jersey) topsoil, and world-class ingenuity.

The Greensward Plan for Central Park became an enormous public works project employing thousands in the service of an aesthetic ideal. Four roadways, sunk to a depth of eight feet to preserve the park’s surface vistas, would join the East and West sides. (How many times have you taken a taxi across the park, the road dipping down without realizing the rationale?) As is true of many parks, this massive undertaking had an aspect of social welfare, as well. Immigrants were crowded in neighborhoods to the south, and fresh air would be at least a partial antidote to the spread of disease.

Central Park was completed in 1873; its design owed much to the precepts of Capability Brown, “England’s greatest gardener,” who had died nearly three-quarters of a century earlier. His pastoral visions were a huge influence. Instead of the more formal Continental gardens with their precise, straight paths and rigidly trimmed plant materials, Olmsted and Vaux plotted their American parks with the naturalistic contours espoused by Brown. Less than a decade into the realization of Central Park, the president of Brooklyn’s Parks Commission, James S. T. Stranahan, asked them to design another site, endowed with natural resources and beautiful woodlands, in what was then, America’s third largest city after New York and Philadelphia.

The story is widely reported—at least in Brooklyn—that Olmsted and Vaux “practiced” when designing Central Park and then perfected their plan in what became the 585-acre Prospect Park, learning from their mistakes. They laid out areas with sweeping lawns punctuated by water features and clumps of woodland with names like The Long Meadow, The Ravine, and Nethermead (who wouldn’t want to explore Nethermead!?). Taking full advantage of the site’s ancient glacial rock formations, they created the park’s stone archways and stairs climbing next to natural waterfalls.

Around every bend and scattered throughout the park are rustic bridges, monuments, and Adirondack-style stick pergolas interspersed with neo-classical follies such as the 1904 Peristyle, a mini-Parthenon designed in the Beaux-Arts style by protégés of renowned architect Stanford White to serve as a croquet shelter. On the park’s outer edges are additions made during Robert Moses’s tenure (1934-1960) as director of New York City’s Department of Parks and Recreation; some were WPA projects that put people back to work after the Depression. This was a time when public parks, with their playgrounds, ballfields, bandshells, and barbecue stands, became venues for expanded family life.

Today, there are people everywhere, with strollers, on skates, and reading on shaded benches. Children dart around statues of famous musicians in the Concert Grove, where more formal terraced gardens are worth exploring. Not far away is the new $74 million Lakeside Center, which includes an outdoor skating rink and a covered skating area that has replaced the old Kate Wollman Rink, like the one in Central Park. The Concert Grove Pavilion is close by, built in 1874, with its recently restored stained glass roof supported by replicas of Hindi columns. At the edge of the 55-acre (fishable!) lake is the very grand c.1905 Boathouse at the Lullwater—a romantic spot for a structure that looks as if it could house a ballroom. It was saved from demolition, with only 48 hours to go, and now houses the Audubon Center. Close-by is one of the most exceptional specimen trees in the park, the Camperdown Elm, planted in 1872.

The historic main entrance to the park at Grand Army Plaza provides a majestic approach and connects with the Olmsted and Vaux design for the first urban parkway—Eastern Parkway, still one of Brooklyn’s beautiful avenues—with greenway buffers separating sidewalks and roadway.

In the radial at Grand Army Plaza is the majestic Soldiers and Sailors Arch built in 1892, with a fountain at its center. It is Brooklyn’s own Arc de Triomphe and, as in Paris, is circled by lanes of rushing traffic. But across the plaza, stepping into the park, one has left the noise behind and entered a pastoral world. Marking the entrance are large flower-filled stone urns, their intriguing handles of entwined snakes symbolic of the Eden waiting ahead. Straight across the road and down a rustic wooden stair is Long Meadow, its vast rolling space coming as a surprise as it unfolds for most of a mile in front of you, with paths disappearing off to the left and right under arched bridges. Dogs are welcome to run off-leash during early morning hours (up to 9 am), a park policy that fosters gatherings of people chatting with coffee cups in hand, and hundreds of dogs romping all the way down the meadow; there is even a Dog Beach at the lower pool. In winter, the fields are a snowscape crisscrossed with ski tracks; in summer, grassy oases become urban beaches, and Frisbees fly. Festivals highlight the many nationalities that have always made Brooklyn a cultural crossroads. The fact that the park is so well used creates a feeling of community and general safety. It is beautiful in its natural state but also fascinating for visitors in the 21st century, who see the ornamental overlay its 19th-century designers deemed appropriate. Today, Prospect Park is the living, beating green heart of Brooklyn, lush and pastoral—like Central Park—a perfected plan!

The original piece appeared in The Garden Club of America’s Fall 2015 Bulletin. www.gcamerica.org.