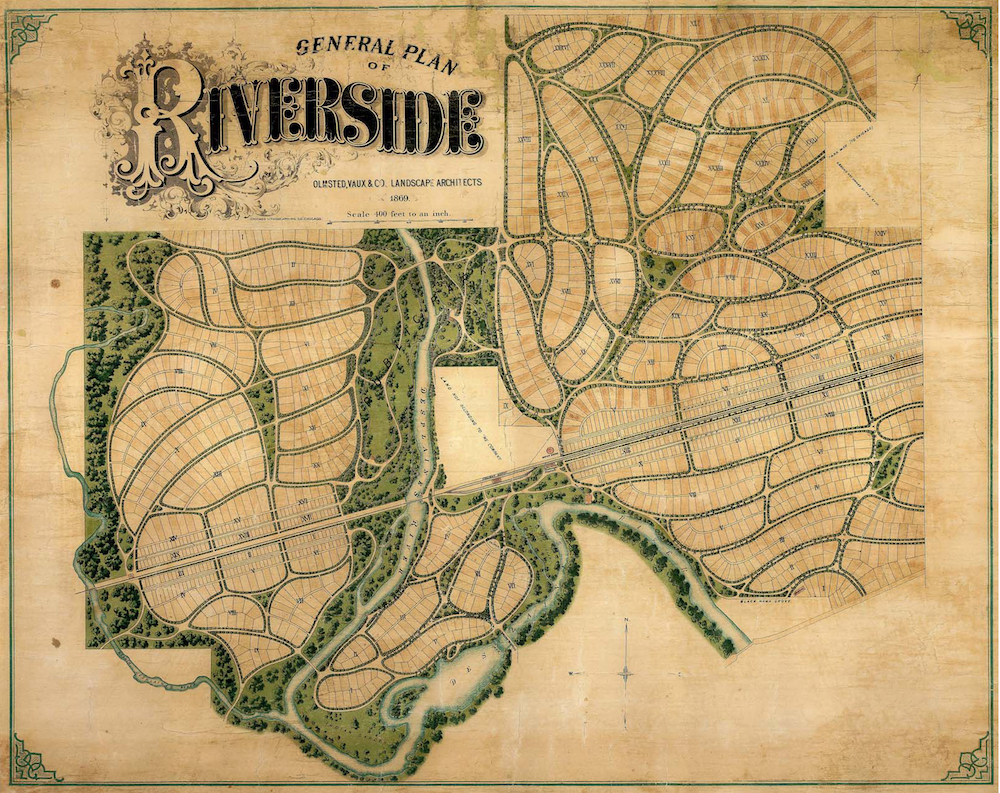

“No great town can long exist without great suburbs,” wrote Frederick Law Olmsted in 1868. At the time Olmsted and his then partner Calvert Vaux were designing Riverside, a 1600-acre suburb of Chicago. The suburban and town planning work of Olmsted and his sons clearly demonstrates the full range of social, economic and environmental concerns that their designs addressed. More than 475 proposals for or inquiries about subdivisions and suburban communities had a job number assigned to them by the Olmsted firm. These projects varied greatly in the degree of the firm’s involvement, with many showing no activity beyond initial correspondence. It is estimated that one or more plans were prepared for only 370 of these projects. The undertakings in this category also varied greatly in scale, from the modest estate of a single landowner seeking to subdivide his holdings, to a twenty-five square mile area on the Palos Verdes peninsula near Los Angeles.

While much of the subdivision work took place in the northeast, the firm was active across the country and in Canada, particularly in cities in which it would have been familiar to clients through its work on urban parks and regional or state park systems. The 1890s and the first decade of the twentieth century were a time of growing activity in this field for the firm. By the 1920s, when suburban America was growing at twice the rate of its central cities, the design of residential communities represented a significant portion of the firm’s overall business. After World War II, the number of such projects dwindled.

Frederick Law Olmsted’s suburban work reflected his romanticized nineteenth century view that a suburb, if well planned, would combine the charm of the country with the convenience of the city. It would provide “the most soundly wholesome forms of domestic life,” and demonstrate “the best application of the arts of civilization to which mankind has yet attained.” The planning work of his sons reflected an early twentieth century confidence that technology and the expertise of planners, administrators and design professionals could be harnessed to shape well-ordered, functional communities. Suburbs, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. held, required the kind of professional planning heretofore only seen in urban design and large-scale landscapes like Central Park. It was crucial to apply the emerging science of city planning to these suburban additions.

As with their park plans and other landscape designs, there is no formulaic “Olmsted style” that can be associated with residential communities: each plan is sensitive to its locale and topography. The articulation of boundaries; differentiation of street width according to type of traffic; provision of common spaces and other amenities that enhance the character of a place and encourage social interaction; and use of deed restrictions to enforce maintenance and preserve architectural and other community standards are hallmarks of the firm’s suburban work that continue to influence suburban design today. The Olmsteds believed the residential suburb was deserving of the best efforts of planning and design professionals. In this complex cooperative enterprise, it is the comprehensive master plan, as Olmsted Jr. stated, that is key to creating “harmonious, beautiful and convenient residential communities.”