Frederick Law Olmsted is the pioneer of landscape architecture in the U.S., the creator of green space masterpieces that dot the country. But perhaps the greatest testament to his genius is how very little one needs to know about him in order to appreciate his work.

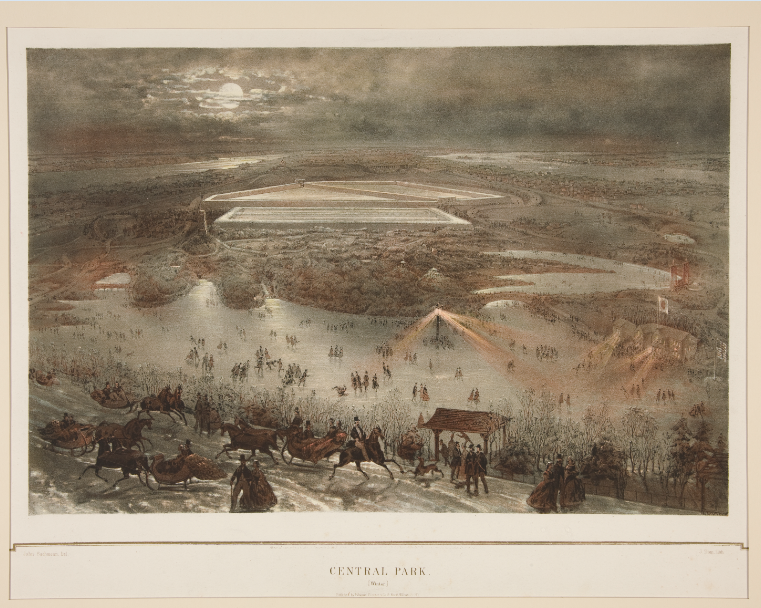

That has certainly been my experience. Back in 1987, I moved to New York, after growing up in Kansas City. On my first day in the Manhattan, following a hectic round of job interviews, I made my way to Central Park. I simply knew this would be a place where I could relax, slough off some urban stress. I still remember my first impressions. I was amazed by how quickly I was able to leave the city, and make my way into the heart of the park. The diversity–in terms of types of people, languages spoken, activities engaged in–was breathtaking. When I visited the Ramble, I got hopelessly lost. My ears told me the city was mere yards away, yet I kept re-encountering the same landmarks, as if I’d happened into the Blair Witch Project.

At this point, I’d never even heard of Olmsted and Vaux. Yet their design intentions were working on me just the same. Getting lost in the Ramble: that was no accident. As it happens, the Ramble was Olmsted’s favorite feature of the park; he tinkered endlessly to lend this modest, 40-acre, city-bound plot the illusion of being an untamed swath of wilderness.

And the diversity I encountered: also by design. Olmsted and Vaux opted to make their park design naturalistic. This was such a stark contrast to the European imperial parks common to that era, filled with triumphal archways and elaborate tiered fountainry, celebrating kings and generals. But Olmsted and Vaux recognized that nature is egalitarian, belongs equally to everyone. Thus, they expected that all kinds of people, from all different backgrounds, would comfortably mix and mingle in their creation. Olmsted described Central Park as “a Democratic achievement of the highest significance.”

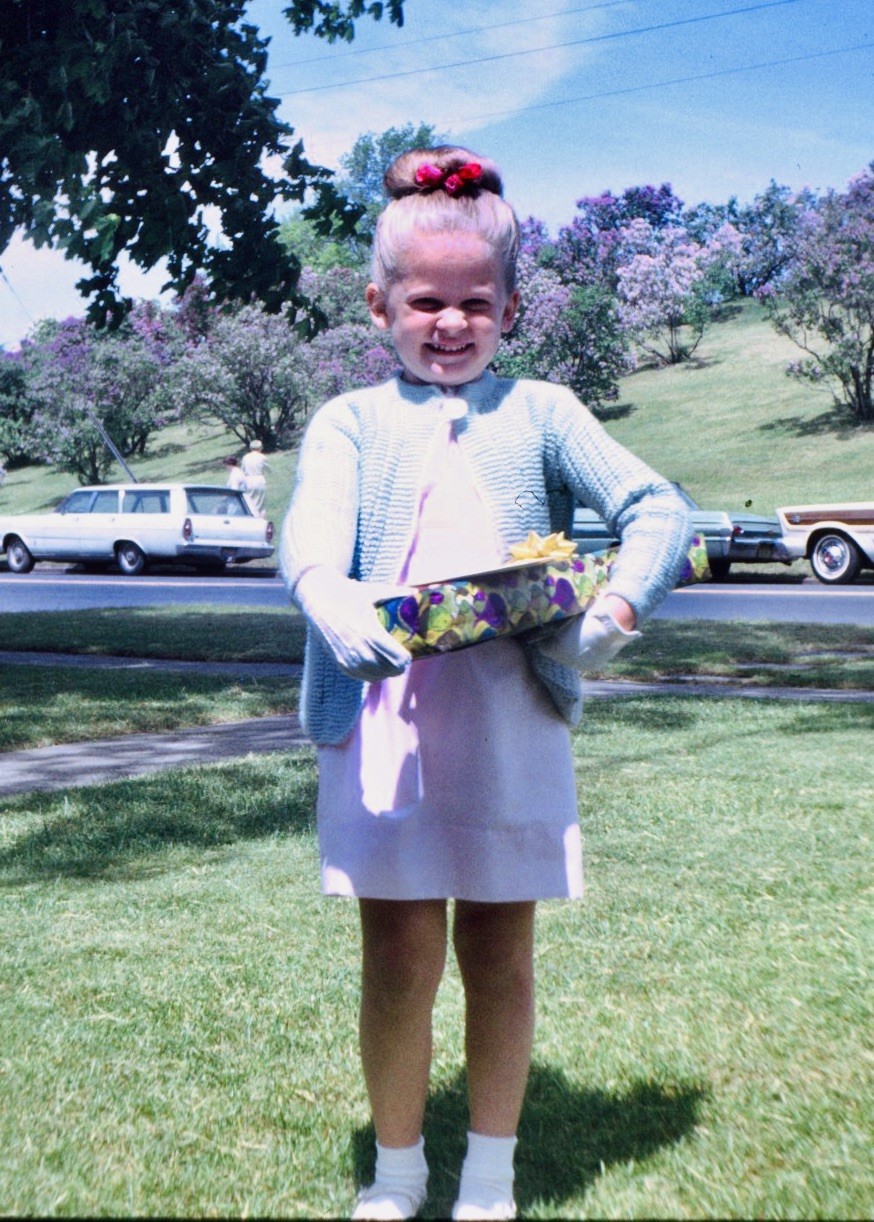

After a few years in Manhattan, I met my future wife, who hailed from Rochester, New York. As I’d later learn, Olmsted played a role in her life, too, long before she could have picked him out in a lineup of historical figures. She grew up a few blocks from lovely, FLO-designed Highland Park. And she has vivid memories of exploring what the neighborhood kids called “rooms of trees.” These consisted of groupings of one type of tree–pines, say–each featuring a conspicuous gap. It’s only natural to wonder what’s on the other side of the gap. Walk through it, and one enters a fresh “room,” surrounded by a different species of tree. As it happens, this Highland Park feature is a stellar example of one of Olmsted’s most hallowed design techniques, what he called “passages of scenery.” But such knowledge is hardly necessary to appreciate Highland Park. As my wife discovered as a little girl, wandering from tree room to tree room is simply what one is inclined to do.

Eventually, I settled into a career as a writer. After several books, I embarked upon a biography of Olmsted. I visited a number of Olmsted sites and gained a deep knowledge of his work, I’d like to think. Yet I’m constantly reminded that appreciation of Olmsted is not cerebral. He’s an artist of the heart, not the head.

This past winter, I faced a minor disaster when a hundred-year-old pipe in my house burst. (I live in Forest Hill Gardens, a neighborhood designed by FLO Jr., but that’s another story.) Because Covid rates were high, I didn’t feel comfortable staying in my house while workers fixed the pipe. My family moved temporarily to an Airbnb in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. My original plan was to walk around, explore a neighborhood I don’t know well. Instead, I found myself heading directly for a place I’ve visited countless times, Prospect Park, almost as if pulled by a magnet.

Olmsted again–working his magic. During the 19th century, there was a popular notion that a park could serve as the “lungs of a city.” FLO worked in an era of crowded tenement living, and rampant disease. But it struck me that our present moment isn’t so far removed from the ills of the past. In crowded New York City, during a terrible pandemic, my instincts inexorably led me to Prospect Park. And I wasn’t alone. On that bitterly cold January day, the park was filled with people seeking the safety of a healthful, outdoor, greenspace.

To appreciate one of Olmsted’s masterpieces, one need not be familiar with a single principle of landscape architecture. One need not even know his name. Ironically, that is one of the main reasons we’re preparing to celebrate this American visionary on the bicentennial of his birth.

Justin Martin is the author of Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted (Da Capo Press).